A qualitative study sought to understand how internalised stigma affects HIV self-care among gay and bisexual men living with HIV who use substances. Men in this cohort experienced self-stigma stemming from multiple intersecting identities, including their HIV status, sexual orientation, race, effeminateness, poverty, and housing instability. Self-stigma around drug use was reported as the most burdensome stigma, as well as the largest barrier to HIV self-care.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that in 2018, only 65% of gay and bisexual men living with HIV in the United States were consistently seen for HIV care appointments and only 57% were virally suppressed. Further, evidence shows that gay and bisexual men who use substances, especially stimulants, often have less than optimal adherence to HIV care and inconsistently access HIV services.

The negative impacts stigma has on health are well documented. So is the impact of internalising these negative messages, or self-stigma. Prior research shows that HIV self-stigma is a barrier to HIV care, and that self-stigma around sexual orientation and/or drug use also present barriers to HIV care. This new study expands on our understanding of self-stigma as a barrier to HIV care as the first of its kind to look at the intersection and impact of multiple self-stigmas on HIV care behaviour.

Led by Dr Abigail Batchelder of Massachusetts General Hospital, this qualitative study sought to examine the impact of these intersecting stigmas experienced by gay and bisexual men living with HIV who use drugs through in-depth interviews. They recruited participants in the Boston Massachusetts area through advertising and outreach at diverse community locations and online through dating, hook-up, and social media sites.

Eligible participants were living with HIV, reported substance use (including alcohol) in the previous three months, were men who had sex with men, and were sub-optimally involved in HIV care. This was defined as having a detectable viral load, reporting less than 90% adherence to antiretroviral therapy, or missing two or more HIV care appointments in the previous year without rescheduling them.

Thirty-three men were included in the study. The average age was 51 and participants had been living with HIV an average of 19 years. Sixty per cent of participants were Black and 36% were White. Thirty-six per cent of participants had a high school education or less, while 46% reported some college and 5% reported advanced degrees. Three quarters of participants made $20,000 or less annually.

Over half (58%) of participants identified as gay, 27% as bisexual, and 15% identified as “other”, which included straight. Most participants used multiple substances. Stimulant use was high (79%), as was tobacco use (76%), cannabis (67%), club drugs (40%), and alcohol only (18%). Most participants also reported using multiple substances, such as alcohol with stimulants (36%), alcohol, stimulants, and sedatives (15%), and alcohol, stimulants, opioids, and sedatives (12%).

The majority of participants reported some form of internalised stigma which impacted their HIV self-care, including self-stigma around HIV, sexual orientation, race, effeminateness, poverty, and housing status. Almost all participants reported self-stigma around drug use. Around half of participants explicitly discussed the intersection of their identities, and stigmas.

Participants emphasised how aspects of their identities were interrelated and could not be experienced singularly. The multiple stigmas compounded each other, affecting how men were judged by society, leading them to judge themselves:

“They think… you’re not only HIV, but you’re gay, you’re an addict… and it’s like, why are you even existing on life? ..That’s what my mind tells me …”

Many men perceived stigma from others, discussing rejection and a lack of belonging from their families and communities. This enacted stigma led to feelings of shame and internalised stigma:

“The society – they judge you. They judge you for the way you’re dressed, the colors you wear, the way you wear your hair. So you have all these things that’s not condoned, so, inside you’re hiding and covering up. So it takes it to … you don’t want to be exposed, but you want to be accepted, so you have all these things fighting with you inside you. Sometimes I want to take a stand publicly – then the fear of being exposed or ostracized or revealed or whatever – I don’t do it. Then I feel ashamed. Some part of me feels ashamed.”

Men is this study explicitly discussed being stigmatised and othered within communities they belonged to, such as the gay or HIV-positive communities, for personal characteristics such as effeminateness or housing instability. Participants who were religious, particularly Black men, also discussed this in-group stigma, noting that stigmas were exacerbated within the religious community.

One participant who identified as straight said that:

“… the culture specifically that I largely identify with, the Black community and the Black church; those are two communities that are much of my identity. But, both of these have a lot of stigma around HIV, around sex, around sexuality.”

However, while almost all Black participants described racial discrimination as a challenge, being part of the Black community and being part of the Black church was described as a source of strength and belonging.

Few participants explicitly connected internal self-stigma around HIV status or sexual orientation as being related to their substance use. However, the men in this study described experiencing enacted stigma and discrimination related to multiple aspects of their identity. This led to feelings of shame and self-judgement. This internalised stigma both perpetuated and worsened substance use:

“Why can’t they just accept me for who I am? … and from there, it’s…downhill, because I start feeling bad about myself… I don’t want to feel that pain, so I’m going out to use. I’m going out to drink.”

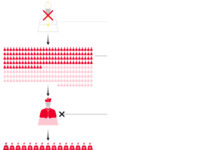

Nearly all reported internalised self-stigma around substance use contributed to that use, more so than any other stigma. It was described as a cycle:

“You use drugs because you’re miserable. But you’re miserable because you use drugs. It’s like a Catch-22.”

“The multiple stigmas compounded each other, affecting how men were judged by society, leading them to judge themselves.”

In this cycle, substance use to alleviate negative emotions resulted in more negative emotions and further use:

“I think what happened to me when I started using was the reason I’ve plummeted more into it… I was trying to numb every aspect of my emotions … I was trying to kill anything that felt vulnerable, like emotions. And I went from just puffs to at one point using the needles.”

This cycle often started a cascade leading to HIV care disengagement, isolation, and further self-stigma:

“I’ll go get high and I won’t take my meds, and it’s just like, I’ll destroy – because …people will be calling me and I’ll avoid people. And then I won’t care. I won’t care about myself, …”

Most participants reported self-stigma around substance use and the substance use itself as impacting HIV care behaviours:

“Sometimes … I don’t even like pills. I’ll do crack. That’ll solve it. (laughs) I’ll do alcohol. In my mind, that’ll solve it. But in reality, it doesn’t… Because I don’t have to think about anything. It takes me away from thinking about me and my life, and living with HIV, being gay, all that… It takes me away from myself so I don’t have to deal with myself.”

The results to this study offer the first look at how intersecting stigmas contribute to sub-optimal HIV care among gay and bisexual men living with HIV who use drugs. The most striking finding was that self-stigma around substance use was the most burdensome, had a cyclical relationship with substance use itself, and was the largest barrier to HIV self-care compared to the other stigmas. These results can help inform future research and interventions.