LGBTQ History month

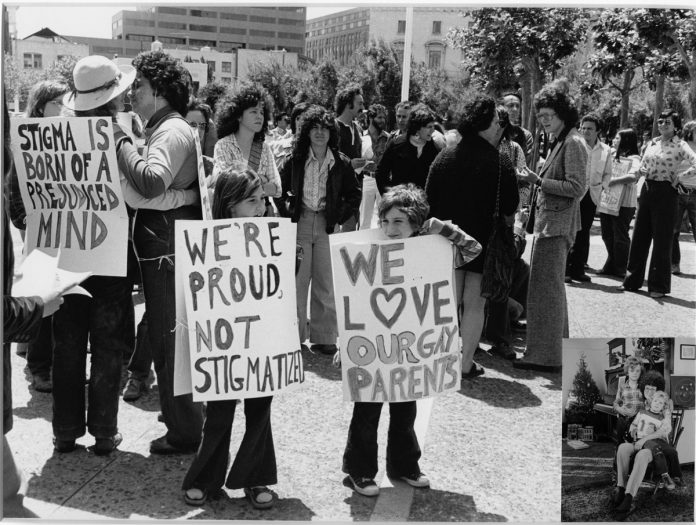

Shot with black and white film two small children stand outside in a San Francisco public plaza draped in protest signs. One reads, “We’re Proud, Not Stigmatized.” The other declares, “We Love Our Gay Parents.”

In the right background of the photograph, taken June 3, 1977, can be seen Harvey Milk, the gay civil rights leader. He would go on to become the first LGBTQ person elected to public office in both the city of San Francisco and the state of California that November.

The image was taken by photographer Cathy Cade, a longtime lesbian activist, and is titled “Rally for Jeanne Jullion.” According to a note about the photo, Jullion was a lesbian mother ensnared at the time in a custody battle for her kids.

She can be seen on the right side of the photo wearing glasses and a two-piece pantsuit talking to a woman whose back is facing Cade’s camera lens. Jullion is also shown in a smaller picture with her two sons, superimposed on the bottom right of Cade’s photo.

It is part of the online Hormel LGBTQIA Center Collection maintained by the San Francisco Public Library. It consists of digitized photographs, manuscripts, documents, and other primary source materials from the James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center housed at the city’s Main Library in the Civic Center district.

The site went live last December and allowed the library’s Digi Center to aggregate LGBTQ historical photos that had previously been published in other sections of the library’s main website so they were easier for researchers, students, and others seeking out LGBTQ material to find.

“I think it is a great way to share the archive with the world,” said Dee Dee Kramer, a lesbian who is the manager of the library’s Digi Center, in her first press interview about the LGBTQ archival digitization effort. “People think of libraries as having books you check out. But we also have archives like photos, government records, or people’s personal stuff that is unpublished or unique and doesn’t exist in other places. Being able to share that online I think is really special.”

New LGBTQ archival items have since been uploaded to the library’s online repository, including a micro-section titled “Preserving LGBTQ Historical Highlights” that went live in June during Pride Month. It was funded by a $7,020 grant the library received in 2019 from the California State Library and includes a wealth of material related to Milk.

One highlight is an audio recording of one of the three “Political Will” tapes Milk made in case he was assassinated, which tragically ended up occurring the morning of November 27, 1978. Disgruntled former supervisor Dan White shot dead Milk and then-mayor George Moscone inside San Francisco City Hall.

There are also a number of Milk’s writings, such as his “Milk Forum” column that ran in the B.A.R., and an edited copy of his famous “You’ve Got to Have Hope” speech he gave June 24, 1977.

Throughout the 11 pages are handwritten edits made to a typed copy of Milk’s speech, including to the final, and most famous, line of it, “You got to give them hope.” Crossed out is the word “I” and a verb that is unable to be discerned in front of the word “you,” while the word “must” that initially had been typed with an underline is crossed out and replaced with “got to.”

“Harvey’s will and speeches are in such incredible demand,” noted Kramer. “School students from across the country want to look at the speeches.”

Now they can do so without having to physically travel to San Francisco, added Kramer. They also now have digital access to LGBTQ material at a time when public libraries and school districts across the country are banning LGBTQ books and curriculums at the urging of right-wing leaders and conservative parents.

“We live in a time where we can make them available to anyone with a browser and an internet connection. It is just huge,” said Kramer, who formerly had served as program manager for the James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center. “I think for queer people, too, it really has changed the game in being able to find context for yourself and other people.”

Effort delayed by pandemic

The effort to digitize the library’s various LGBTQ historical holdings was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, as the city in March 2020 shuttered its public libraries and reassigned library staff members to assist in dealing with the health crisis. Kramer worked as a contact tracer, calling people who were potentially exposed to the coronavirus, for instance, and helped distribute food to those in need.

When she returned to her library duties in July 2021, Kramer took over as the Digi Center manager and found the LGBTQ digitization effort among her to-do list. The center oversees DigitalSF, which is the website for the San Francisco Public Library’s Digital Collections, and has wanted to increase its digitized holdings accessible to the public for years.

Kramer and her colleagues first set about on a plan to make it easier for people to find the digital material the library had already posted online. They also worked on how to display the material and what navigation tools to include for them.

They have also been creating a better catalog for the materials already digitized and adding them to the correct collections on the DigitalSF website. For instance, more of Cade’s photos in the library’s holdings should be added in time to the lone one of the Jullion rally currently found on the webpage for the “Cathy Cade Photographs Collection.”

The same is true for the “Chloe Atkins Photographs Collection,” which as of now also has just one photo posted online in it. But a finding aid for the Hormel center’s holdings of Atkins’ decades-long career photographing the Bay Area’s lesbian scene indicates there are countless more of the photographer’s works that could be added to the digital archive.

The library’s digital records for the pioneering gay rights activist Harry Hay are far more extensive. The webpage for the “Harry Hay Papers” has 50 different items, including a 1935 black-and-white portrait of a dashing Hay with his right arm in salute.

There is also a trove of photos from negatives taken during San Francisco police investigations from 1945 through 1969 into bookstores, sex-oriented businesses, theaters, and art shows that featured gay and LGBTQ content. Another collection features a scrapbook from the 1950s detailing the arrest and trial of Grace Miller and Joyce van de Veer, the owners of several bars frequented by gays and lesbians.

One project Kramer said the Digi Center is working on is scanning books of mug shots taken by the police of suspects arrested decades ago on sodomy charges and other sex-related crimes. The historical material provides a unique look into that era of LGBTQ history, she noted.

“It makes for useful research and a whole different kind of lens to look through,” said Kramer.

The Digi Center also wants to digitize the photos in the library’s Tenderloin Times Photograph Archive, which also relates to LGBTQ history. The publication’s coverage of the city’s Tenderloin district and its many LGBTQ residents includes photos of early AIDS protests and other LGBTQ demonstrations and events.

“When you sort of queer the archives, it is not just going to be the Hormel center where these materials arise,” noted Kramer.

There are currently two-dozen different LGBTQ digital collections on the library’s website, with more to be added in the coming months. During LGBTQ History Month in October, Kramer hopes to add two collections featuring the works of photographers Robert Giard and Rick Gerharter, two gay men who helped to document the LGBTQ community on both coasts. Giard, who died in 2002, documented the theater scene in New York City, while Gerharter for decades has taken photos for the B.A.R. of the Bay Area LGBTQ community.

While the digital archives do not replace the need to protect the physical materials housed at the library’s Hormel Center and San Francisco History Center, Kramer said, they do play an important role in the preservation and distribution of the archival holdings.

“Digitizing is not preserving,” she noted. “But if you have a tape that is 30 years old, the sound quality is going to degrade. So digitizing it is one way to migrate it to a format that people will continue to have access to it. This way it is still playable and listenable.”

Growing up in North Carolina in the 1970s and 1980s, Kramer said she wishes she had access to such LGBTQ material. It can be empowering for people who otherwise feel invisible, she noted.

“When you are able to go on a site and see these things, it changes lives,” said Kramer. “When people go online and find something they recognize or see themselves in, it is a really big deal.”