Twenty years ago, on one of America’s darkest days, two planes flew into the twin towers, another into the Pentagon, and a fourth crashed in a field in rural Pennsylvania.

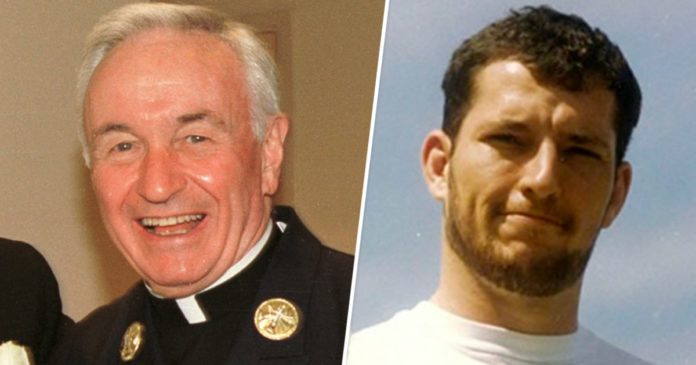

But even during the tragic early morning hours of Sept. 11, 2001, there were heroes. People like Mark Bingham, who was aboard United Airlines Flight 93 when it went down near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. And the Rev. Mychal Judge, who was tending to victims in the World Trade Center’s north tower when debris from the collapsing south tower killed him and many others.

On the face of it, the two men couldn’t have been more different: Bingham was 31 when he was killed; Judge was 68. Bingham, a former college rugby player with a 6-foot-5, 220-pound build, was a gay public relations executive with an active dating life. Judge was a kindly Franciscan friar who was “selectively out,” according to longtime friend and LGBTQ activist Brendan Fay.

But both men showed courage beyond comprehension that day, saving lives and perhaps even souls.

Along with Todd Beamer, Tom Burnett and Jeremy Glick, Bingham confronted the four hijackers aboard United 93. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, their actions ultimately led to the plane crashing in an empty field instead of slamming into its intended target, likely the White House or the U.S. Capitol.

Bingham had enough time to call his mother, Alice Hoagland, to explain what was happening and tell her he loved her.

“I only got three minutes with him and when I tried to call back, I couldn’t get through,” Hoagland told the Iowa City Press-Citizen in 2019.

The chaplain for the New York City Fire Department, Judge rushed downtown when he heard the World Trade Center had been hit and provided aid to the injured in the area and prayers for the dead.

He then entered the north tower, where a command post had been established, and continued to minister to rescue workers and those trapped in the building. Judge was administering last rites when he was killed, The Irish Times reported in 2018, and praying, “God, please end this.”

But there were other threads that connected Bingham and Judge besides their bravery, including their zest for life.

Judge “had a bursting-at-the-sides sense of humor,” said Fay, who co-produced the 2006 documentary “Saint of 9/11.” “He loved to sing and was a real jokester, with a laugh that would fill a room.”

Bingham, once the president of the Chi Psi fraternity at University of California, Berkeley, “was the life of the party,” said Amanda Mark, his roommate in New York and longtime friend. A 2001 Advocate profile recalled Bingham drunkenly running on the field at a college football game to tackle the opposing team’s mascot.

And, according to those who knew them, they both went through a journey of accepting their sexualities.

Like a lot of young gay men of his generation, Bingham struggled to some degree with his sexual orientation. He had come out to his fraternity brothers and his mom, but he wasn’t entirely out at work. Even when he first started playing in a gay rugby league in San Francisco, he had his face blurred in photos in the local press.

“San Francisco didn’t serve as a beacon for him as it had to so many others,” Jon Barrett wrote in the preface to his 2002 biography “Hero of Flight 93.” “He lived there by default, for the most part. His family had moved to the Bay Area in the early 1980s, and most of them were still there.”

Mark recalled how one night, after Bingham relocated to New York and moved in with her, he confessed he wanted “to write the Great American Novel — but gay.”

“So that you’d have to read it in high school, and people would understand that gay people were always among us and were totally normal and a part of our lives,” she said.

Judge’s sexual orientation was not made public until after his death, but he did actively minister to New York’s LGBTQ community in the 1980s and ‘90s and form one of the first Catholic AIDS ministries.

Fay met Judge in the 1980s through the LGBTQ Catholic organization DignityUSA. He said the FDNY chaplain “was out to friars and friends and people he could trust — or people he thought coming out to would help, like parents wanting to support their gay children.”

Judge was one of the few priests who would conduct Mass and provide sacraments to Dignity members.

Immediately recognizable in his brown robe and sandals, Judge visited people who were sick and dying at St. Vincent’s Hospital’s AIDS ward and lead funerals for the young men when their local parishes refused.

“He’d go to Connecticut, to New Jersey; he’d get on an airplane and fly out to do a funeral in Ohio,” Fay said.

Judge was supportive of groups like PFLAG, a nonprofit group serving LGBTQ people and their families, and wrote one of the first checks for the St. Pat’s for All parade, the inclusive celebration Fay founded in 2000.

“Mychal Judge took risks. He pushed boundaries,” Fay said. “He wasn’t a flag-waver, but he definitely pushed boundaries. He figured out how to weave around and do what he felt needed to be done without suffering the wrath of the church.”

He never missed a Pride parade if he could help it, though he walked with Franciscan brothers. According to Fay, he also regularly attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings for LGBTQ people.

“It was in these rooms where Mychal felt he could be himself,” Fay said.

“In his journals, [Judge] talks about being at peace with his sexuality and grateful that God had made him gay,” said Francis DeBernardo, author of the upcoming biography “Mychal Judge: Take Me Where You Want Me to Go.”

Friends of both Bingham and Judge also recalled their great sense of compassion and tendency to form long-lasting bonds.

When TWA Flight 800 exploded over the ocean near East Moriches, New York, on July 17, 1996, Judge showed up for several days and forged close relationships with many grieving families.

“When he connected with you in a moment of struggle, very often he stayed with you for life,” Fay said.

Mark had met Bingham in 1988 when she was in high school in Australia and he was part of a group of American teens who came to play rugby in an exhibition. Over the years and across two continents, their bond grew closer.

“Rugby taught Mark to be a team player,” she said. “When you joined the team, you were part of the family. When another player was advancing to the goal line, he’d shout, ‘I’m with you! I’m with you!’ That’s what you say in rugby, but it really embodied everything Mark was about. He couldn’t tolerate unfairness or injustice, and he wasn’t afraid to stand up for the people he loved.”

She called Bingham “the great connector” for his ability to bring disparate groups together. He was always making new friends while still reaffirming bonds with old ones — through phone calls, emails and surprise visits.

Once, when she and her friends returned home to one of their houses in Sydney, they found Bingham waiting for them in the living room. He had flown in unannounced from the U.S.

“He’d say, ‘Let’s keep in touch,’ and he would. And he’d arrange to see you when he was in town,” she said. “He would have just loved Facebook.”

A rugby player at UC Berkeley, Bingham continued to play the sport after moving to San Francisco. He even became a key figure in the creation of the International Gay Rugby league in 2000.

Just months before he died, Bingham was at the league’s first invitational in May 2001, helping the San Francisco Fog defeat the hometown team, the Washington, D.C., Renegades, in a 19-0 shutout.

At the time of the crash, Bingham was working to bring a gay rugby team to New York, which led to the formation of the Gotham Knights.

“Mark’s two worlds were rugby and being gay, and when those worlds collided, he was ecstatic,” Mark said.

After the terrorist attacks, when it became public that Judge was gay “there was a big debate in Catholic circles,” said DeBernardo, executive director of New Ways Ministry, which advocates for inclusion for LGBTQ Catholics.

“People couldn’t resolve the fact that a gay person could be holy and selfless,” he said. “It was like cognitive dissonance. I wasn’t even totally convinced he was a gay man until I started doing the research [for the book].”

But, he added, Judge’s whole sense of ministry, of being of service to others, came from his coming to terms with being gay.

“He had empathy and sensitivity to being on the margins,” DeBernardo said. “And he understood the great love God had for him just as he was.”

DeBernardo, like other biographers and friends, said he believes Judge honored his vow of celibacy.

“But speaking to others about how accepting he was of his sexuality — and almost not caring if you knew — I can’t believe he’d want to be closeted now,” he said.

Bingham’s closest friends and family were also ambivalent about his being heralded as a gay hero.

“At first I really felt like his being gay didn’t matter,” Mark said. “Don’t put out ‘gay hero’; he was just a hero.”

But in the weeks after the attacks, she, Hoagland and Bingham’s other friends spoke more about it.

“We decided at that time we should encourage that perspective,” Mark said, “because the truth was there weren’t any gay heroes.”

The gay rugby community wasted little time deciding how to honor their fallen brother: In June 2002, less than a year after the attacks, the inaugural Mark Kendall Bingham Memorial Tournament —commonly known as the Bingham Cup — was held in San Francisco with eight teams.

In 2018, the last year the biannual event was held, the competition welcomed 74 teams from 20 different countries. The 2022 Bingham Cup in Ottawa, Ontario, rescheduled from 2020 because of the pandemic, will include 148 teams.

Bingham never got to write his novel, but the tournament that bears his name imparts the lesson he wanted to share, according to Mark.

“Part of the Bingham Cup journey for so many players, they’ll tell you, is that they wanted to play sport but gave it up because they didn’t think they’d fit in,” she said. “Even though they’d never met Mark, they’d say he changed their life.”

Hoagland was integral in keeping her son’s legacy alive: Before her death in 2020, she regularly attended the Bingham Cup tournaments, where players would chant her name and flock to have their photos taken with her.

One of the tournament’s prizes is called the Hoagland Cup in her honor.

“She was a mother to us all,” Bingham Cup President Jean-François Laberge said. “A lot of members of the IGR movement were abandoned or disowned by their families. She became a mother figure to players across the globe.”

Laberge said he had several discussions with Hoagland and Mark “about the importance of ensuring the tournament not just go on but continue to thrive.”

“All that IGR is, and all that the Bingham Cup has become, carries on Mark’s legacy,” Laberge said. Next year’s tournament will spotlight “our shared values of inclusion, respect and athletic competition,” he added, including a summit on transgender athletes and a wheelchair rugby exhibition game.

At a special dedication ceremony, a Canadian maple will be planted in Ottawa’s Ken Steele Park, where a plaque will officially designate a newly upgraded rugby pitch the Mark Bingham Field.

Judge’s legacy, meanwhile, is both more audacious and more complicated, as supporters redouble their efforts to have him canonized as a Catholic saint.

DeBernardo said a big push for the sainthood movement actually came from the Vatican itself: In 2017, DeBernardo received a call from the Rev. Luis Escalante, an official from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints, suggesting the idea.

“There are many avenues to sainthood,” DeBernardo said. “One is if you are a martyr — someone who dies for the faith. But that year, Pope Francis opened another avenue, ‘the offerer of life.’ Someone who knowingly gives their life as an act of service to others.”

Escalante thought Judge fit into that category, DeBernardo said, “because he went into that building knowing it was very likely he wouldn’t make it out, but he wanted to minister.”

Fay said he understands the desire to have Judge recognized by the church, but he’s not sure Judge would want the honor.

“I think he’d rather there be a shelter in his name for LGBT youth,” he said.

Achieving sainthood is a protracted process involving much research and a lengthy formal investigation. According to DeBernardo, Escalante knew Judge was involved in the gay community and wanted New Ways Ministry to help find people who knew him to provide firsthand accounts or documents “that will give a clearer, more detailed picture of his life, spirituality, and ministry,” DeBernardo wrote in a 2017 post on the ministry’s website, especially “any information regarding a possible miracle attributed to Fr. Judge’s intercession.”

Soon Escalante began receiving testimonies supporting canonization from the many communities Judge touched: firefighters, LGBTQ people, homeless people, AA members and others.

Four years later, on Sept. 2, Escalante called DeBernardo again: The testimonies were helpful, but the process had stalled.

Typically, candidates for sainthood have a sponsor who provides advocacy and fundraising.

“That’s why so many saints belong to holy orders,” DeBernardo said.

But Judge’s order, the Franciscans, declined to sponsor him.

“We are very proud of our brother’s legacy and we have shared his story with many people,” the Rev. Kevin Mullen, leader of the Franciscans’ New York-based Holy Name Province, told The Associated Press. “We leave it to our brothers in the generations to come to inquire about sainthood.”

Escalante implored DeBernardo to encourage a grassroots movement to take up the cause.

On Sept. 11, 2021 — two decades after Judge’s death — New Ways Ministry put out the call for individuals and organizations to form an association to sponsor Judge’s canonization.

In a statement, New Ways Ministry co-founder Sister Jeannine Gramick said she was hopeful people will come forward “so that this priest who symbolized God’s love to so many different communities will be recognized for the way he himself responded to God’s love.”

CORRECTION (Sept. 11, 2021, 12:52 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated the publication year of an article in The Irish Times about the Rev. Mychal Judge. It was published in 2018, not 2011.