For government officials from Los Angeles to Seattle and beyond, 2020 was the year that political protests literally came home to roost.

Demonstrators repeatedly ditched traditional venues, such as government buildings and big commercial streets, to chant, fulminate and sit-in outside the front doors of officials including Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best, former Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey and the county’s director of public health, Barbara Ferrer.

When Sacramento’s mayor and city manager got the same treatment in 2020, the city responded like many of its peers nationally: quietly letting the protesters have their way, in the hope of avoiding violent encounters with police.

That approach ended on the last Sunday of March in California’s capital, at a planned protest outside City Manager Howard Chan’s suburban home. It triggered a massive police response and denunciations from civic leaders, business organizations, a statewide federation of civic officials and even civil rights groups.

“No more,” said an open letter signed by Mayor Darrell Steinberg, his eight fellow City Council members and about 60 other individuals and organizations. “A small group of people willing to embrace violence to advance their ill-defined agenda cannot be allowed to put our city leaders and their families at risk in their homes. Protest at City Hall, not outside someone’s bedroom.”

Protesters face off with police officers outside of the home of Sacramento City Manager Howard Chan on March 29. The protesters targeted Chan for his decisions regarding police officers accused of misconduct.

(Daniel Kim / Sacramento Bee)

The subsequent protest drew only about 30 people and petered out without any serious confrontation. None of the demonstrators, upset at the city manager’s handling of police abuses and winter sheltering of homeless people, were arrested. Chan’s home went undamaged, in contrast to a February rampage in which police said demonstrators tore up Steinberg’s front yard, pelted his door with rocks, trashed a garden sculpture and stole a security camera.

Over the last year, groups on the left and right have taken protests to officials’ front steps, targeting not just thick-skinned career politicians but more obscure appointed bureaucrats. Last year, conservative antimask protesters showed up at the home of Dr. Nichole Quick, Orange County’s chief health officer, displaying a banner depicting her as Adolf Hitler. The doctor resigned days later.

In Sacramento, the more restrained outcome outside Chan’s house felt like a victory to the city’s establishment, allowing reasonable dissent and perhaps taking a small step toward restoring a more traditional notion of what constitutes “the public square.”

Yet friends of the protesters called it an overreaction and said “home visits” will remain a tool in their arsenal. Skyler Henry, a Sacramento musician sympathetic to the “Sactivists,” said two-faced public officials are fair game for such tactics, whether they are city managers or Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, a moderate Democrat from Arizona who recently voted against a minimum wage increase.

“You should be terrorized for the rest of your life. You should never be able to leave your house, if that is how you are going to use your position to govern,” Henry said of Sinema. “The same thing sort of applies with the mayor and city manager of this city.”

Some city officials are countering such rhetoric with strong language of their own.

“If you look up the definition of terrorism, it says it’s using violence or intimidation for political gain,” Sacramento Police Chief Daniel Hahn said. “In my opinion some of these incidents, the way they are trying to provoke fear, are domestic terrorism.”

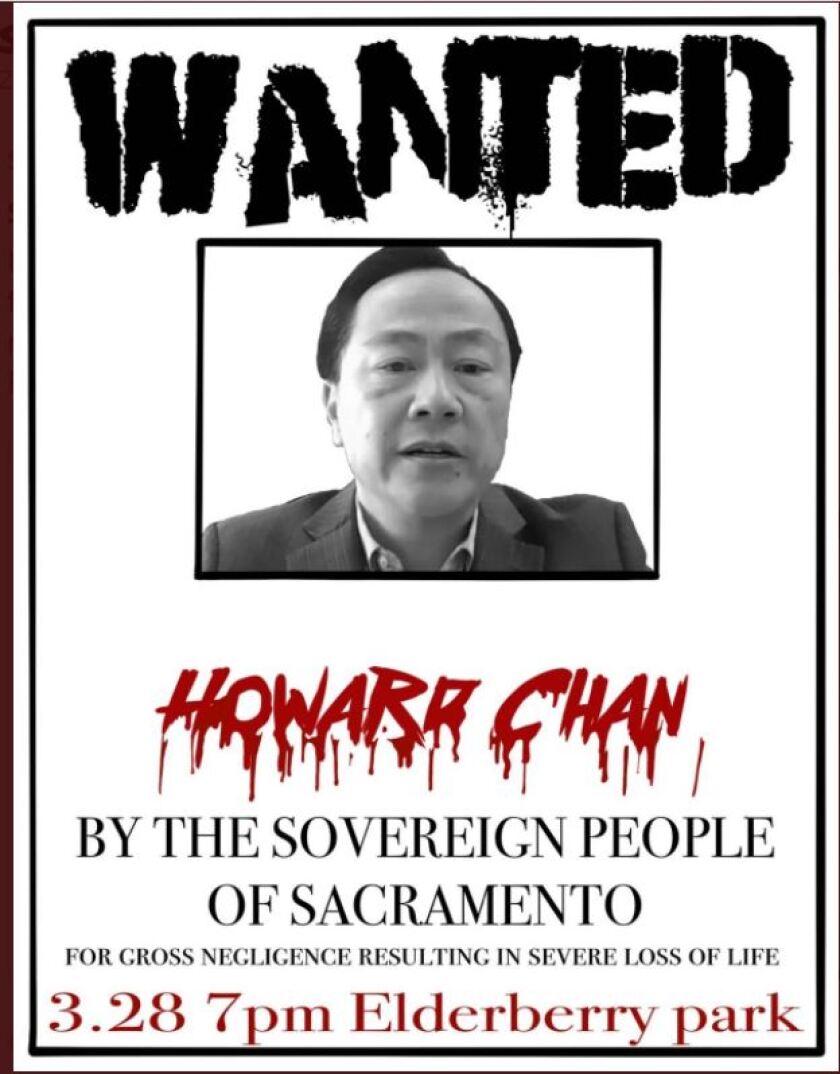

In Sacramento at least, the days of polite tolerance for intrusive protests seem over. Hahn called it a “proud moment” to see a multiethnic group of city leaders condemn the foray to Chan’s home, promoted by “WANTED” posters that depicted the city manager’s name dripping with blood.

Leftist activists angry at Sacramento City Manager Howard Chan created this poster of him that has been condemned by Asian American leaders and others.

(City of Sacramento)

Activists posted a similar image of Hahn, who is Black. But the targeting of Chan, who is Chinese American, provoked particular concern, at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed a spate of hate crimes against Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Sacramento Councilwoman Mai Vang, the daughter of Hmong refugees from Laos, tweeted that the tone was “absolutely reckless & harmful … and particularly dangerous during a time of increased hate and violence against Asian American communities.”

Sacramento’s most divisive political conflicts typically take place at the state Capitol and, to a lesser extent, outside City Hall. But the tone of Sacramento city politics has evolved in recent years in part, some observers say, because of a new generation of more aggressive activists, along with an influx of progressive newcomers from the San Francisco Bay Area.

A flashpoint arrived in March 2018, when Sacramento police fatally shot an unarmed 22-year-old Black man, Stephon Clark, in the backyard of his grandmother’s home.

A series of reviews, including one by the California attorney general’s office, found that police ”reasonably believed” they were in danger when they mistakenly thought that Clark’s cellphone was a gun. Waves of protests followed.

The growth of the homeless population — steadily increasing despite millions of dollars of investment by the city and county — has also frayed tempers. That anger turned toward Chan in January, when a ferocious winter storm swept away dozens of tents and two homeless people were found dead.

Steinberg and three council members had urged opening a “warming center” in a downtown library to shelter the vulnerable. But Chan had deferred to Sacramento County guidelines that require temperatures to dip below freezing three nights in a row before opening emergency facilities. The city manager said he also feared that opening the warming center might spread the coronavirus among the unhoused and city staffers working there. (Two park maintenance workers who staffed an earlier warming facility were infected by COVID-19, though it’s unclear if it’s connected to their work there, Chan said.)

The “WANTED” posters urged demonstrators to congregate near the city manager’s home in North Natomas, a quiet neighborhood of expansive tract homes in a deep floodplain not far from Sacramento International Airport. The poster accused Chan of “gross negligence resulting in severe loss of life.”

The protesters did not respond to a request for comment, placed with a civil rights attorney who said she represented some of them. But a group of four other activists, who regularly convene for a podcast called “Voices: River City,” amplified what they see as the righteous grievances of those who went to Chan’s home.

Podcast host Dave Kempa said Chan, Steinberg and other city officials “have blood on their hands for years of gross negligence toward our unhoused neighbors and a constant, obstinate refusal to hold our police force responsible for their violence.”

Kempa and his three fellow podcasters mocked the notion that the property damage done at the mayor’s house amounted to “violence.”

“They are describing injuring landscaping as violence,” said Flojaune Cofer, a nonprofit healthcare administrator. “I don’t view that as violence. I view that as intimidation. I view that as property damage.”

“Voices” commentators, including Henry, all agreed that Sacramento’s top leaders appear oblivious to the suffering of common people and shouldn’t sleep easy as a result.

“You don’t feel comfort, ever again, until you start ameliorating the pain of the people,” said Kempa, a freelance journalist.

The activists said protests have been redirected to homes, in part, because that’s where most officials spend their days during the pandemic.

The vitriol against Steinberg might surprise conservatives who routinely lash the mayor, reelected in November with 77% of the vote, for being overly progressive.

As a state legislator, Steinberg led a successful ballot measure to generate more than $2 billion a year for mental health care, through a tax on millionaires and billionaires. Previously he founded the Unity Council, in reaction to white supremacists who murdered a gay couple and firebombed synagogues and a women’s health clinic.

The city government he leads, with Chan’s support, has created an office of inspector general to independently review officer-involved shootings, formed an Office of Community Response to remove police from nonemergency calls and approved a policy to minimize foot pursuits by officers.

Sacramento recently opened the first in what it promises will be a series of “safer ground” encampments, places where homeless people can live outdoors, without being disturbed, until more permanent housing can be found.

“This is the the job that I signed up for, so it’s fine. It usually comes from the right, and now it’s from another other side,” Steinberg said. But he added that threats leveled at public officials’ homes “cross a clear line. And most importantly, they don’t work. Come talk to me. Don’t try to intimidate me. It’s not going to move me. At all.”

Chief Hahn said most of the protesters who targeted Chan’s and the mayor’s houses were white. He said they claim they want more diverse city leadership, although belittling him and the city manager, two men of color from modest backgrounds. Chan grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown, the son of immigrants who worked as a hotel maid and a bartender. Hahn is a son of Sacramento’s Oak Park, a historically Black neighborhood.

“Who do they come after? The Black chief of police and the Asian city manager,” Hahn said. “The whole thing is dripping with irony.”

Steinberg recalled how protesters came to his neighborhood last summer and filled the streets with a “die-in” that marked the May police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

“That was very dignified,” Steinberg said, “even beautiful.”

But protests since have become more aggressive.

Roughly 40 demonstrators came to Steinberg’s home in early February, starting with chants and calling out his adult children (who were not home) by name before progressing to pounding on the door.

Steinberg had asked police not to intervene, for fear of a violent clash. He said his attitude changed when rocks began to pelt his front door and windows, worrying that the crowd might even try to force its way inside. With the mayor’s consent, police swept the protesters off the property.

Chan’s home near the city’s north end got its own “home visit” last summer, demonstrators filling the driveway with body bags and the lawn with tombstones, emblematic of those who died in police shootings. Police said protesters banged on the garage and reached over a fence to take cellphone pictures. The intruders blared their demands over a bullhorn, just outside the window of Chan’s brother, who uses a wheelchair.

When she heard demonstrators planned to return last month, Chan’s wife wept. She told her husband that his job was traumatizing their family and that he should quit, Chan recalled. Asian American activists offered to come to the home to confront the protesters, but Chan said he told them he wanted to avoid a potentially dangerous showdown.

“I don’t want any of this. My family is terrified. I feel so helpless. This is not okay,” Chan said in an email to City Council members, asking them for a clear show of support.

Sitting in his backyard five days after the protest, Chan explained his dismay.

“You are protesting me. You don’t have a beef with my family or with my neighbors,” he said. “We can have a discussion about your disagreements. But just not here…. This intimidation factor, it’s just unconscionable.”