All these experiments proved was that it’s quite easy to destroy a mind with fear and lack of sleep; it is, however, impossible to then restore a person’s mind in a controlled way. No matter the extremes psychopharmacologists, behavioral scientists, and neuroscientists went to, the effects of trauma on the mind are simply too unpredictable to turn into a system. The idea, then, of “brainwashing” was always a fantasy, born out of a paranoid and violent era in American history, and it blossomed in parts of the counterculture of the 1970s.

Cult leaders, unlike interrogators, have no need of reliable methods for extracting true information, but they know how to break people. As a longtime resident of San Diego, Dimsdale was stunned to learn of the mass suicide that took place among the Heaven’s Gate movement in 1997. The group was founded in 1974, and members believed that the Comet Hale-Bopp was trailed by a spaceship that would take them to the next life upon their exit from this one; they died in bunkbeds wearing matching sneakers. It was reminiscent of the 1978 mass death at Jonestown, when community leader Jim Jones convinced (and in some cases compelled) hundreds of his followers to commit “revolutionary suicide” at their compound in Guyana.

Contemplating how these leaders cut off their flocks from the outside world, and made them live in cloistered communal conditions, Dimsdale compares these crimes to the capture and conversion of heiress Patricia Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974. She “converted” to her captors’ side, and shot someone at their behest during a robbery. At her trial, Hearst’s lawyers asked whether she could really be accountable for her actions, considering that her captors had kept her in a closet for several weeks, essentially holding her prisoner. The implication of this argument was that personal responsibility is lessened in brainwashed people.

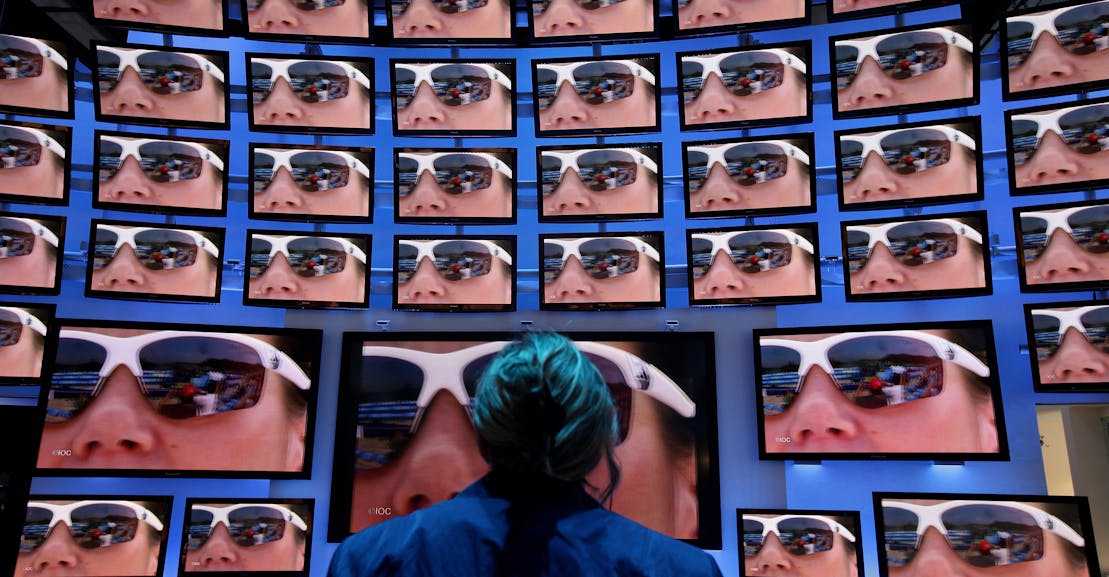

Throughout Dark Persuasion, Dimsdale shows how the idea of brainwashing has been used to justify something much cruder: not the intricate manipulation of another person’s thoughts but simple abuse, whether conducted by the government or by the leaders of a cult. The term always had more political explanatory power than actual psychological basis. If it does have any real meaning, it is as a way of indicating a broader anxiety—about the threat of a hazily understood ideological foe.