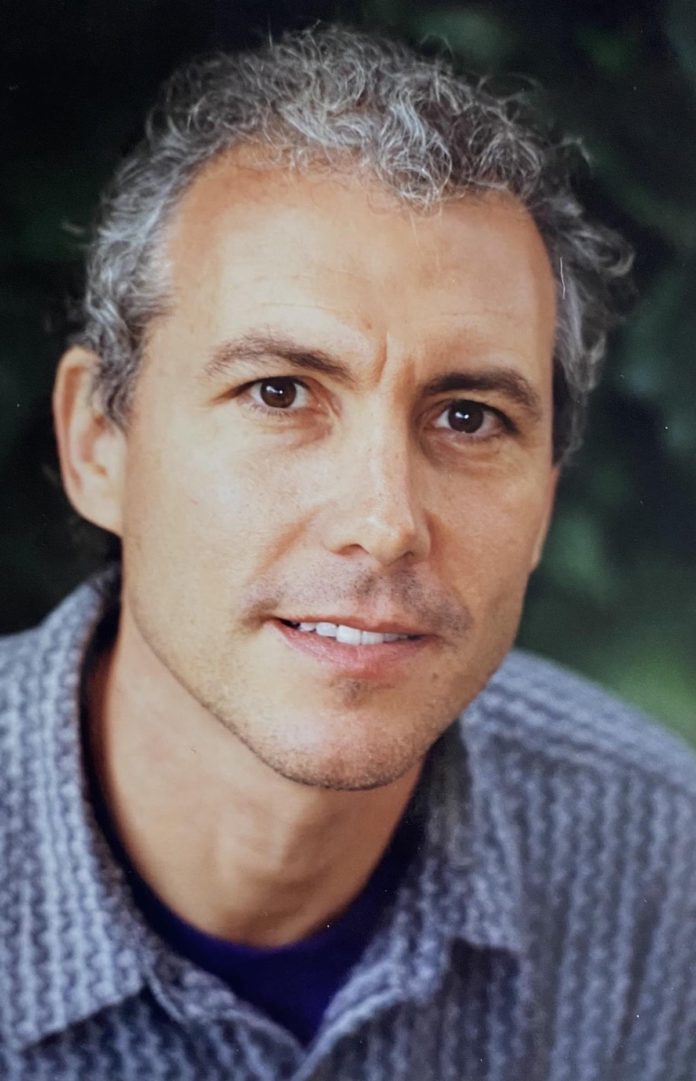

The Berkeley Free Clinic’s longest serving volunteer, and co-founder of one of the nation’s first and longest-running gay men’s health clinics, Dr. Fred Strauss, passed away at his home in Oakland on Sunday, Sept. 26, 2021. He was 72. He took on HIV patients early in the AIDS epidemic and fought for LGBTQ reproductive rights. Fred was a compassionate provider, connecting with, listening to, and teaching both patients and colleagues. In his 48 years in medicine, he was a fantastic, gentle, and caring mentor and friend to many.

Born on Oct. 8, 1948, Fred grew up the youngest of four brothers in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, where his parents ran a grocery store. His upbringing was guided by Jewish cultural traditions brought by his family’s recent immigration experience alongside stories of World War II survival, leading to his lifelong love of Jewish comedy and comfort foods. Fred’s early interest in problem solving and puzzles drew him to UC Berkeley in the late 1960s to study math and computer sciences. As a student he worked as a residence advisor in the campus’ men’s dorm, Bowles Hall, where he fostered lifelong friendships.

After graduation Fred worked for a short period as a public school math teacher in the East Bay before deciding to return to the university to study medicine. He was accepted into one of the first cohorts of the UC Berkeley – UCSF Joint Medical Program. It was during this time in 1973 that Fred began volunteering with the Berkeley Free Clinic (BFC). “It seemed like it had been there forever,” Fred reflected during the BFC’s 50th Anniversary celebration in 2019, “but it had only been around for four years.”

Fred loved and felt rewarded by the grassroots form of medical care practiced at the volunteer-run BFC. He was part of the team which recruited and trained community members to work, under the guidance of doctors, to take on routine exams for things such as colds, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and minor cuts or wounds. He helped run the clinic’s lab in his early years, helped in clinic administration, and became a medic and the coordinator in the Medical Section, all before graduating from medical school.

While working as a BFC medic in late 1975, Fred saw a client who had an STI that he had contracted at a gay men’s bathhouse. The client had gone to Kaiser for help, only to be physically assaulted by a homophobic doctor. As a bisexual who had sought non-judgmental sexual healthcare himself, Fred knew that this client’s experience with homophobia in health care was more the rule than the exception. After Fred helped that client find a supportive provider, the client got back in touch, and along with others they designed a sex-positive STI clinic for the gay and bisexual community.

On a Sunday in 1976, Fred and the crew of gay and bisexual community members they had trained, opened the Gay Men’s Health Collective (GMHC) for services. The shifts were in the evenings, and afterwards all the volunteers would go out for dinner together, creating a non-bar social space for volunteers and making work relations feel more like a family. It was one of the first community-run gay/bi men’s STI clinics (two similar, unconnected programs opened in NYC about this same time, and another opened in Washington, D.C., a few years later), and the only one from that period we are aware of that continues to operate today. Except for a closure at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the GMHC has been open every Sunday since its founding and has seen thousands of people for STI testing, counseling, and treatment. The program has allowed hundreds of queer volunteers to gain experience and inspiration at the GMHC to go on to careers in nursing, medicine, research, and social services in the U.S. and abroad.

After graduating from medical school, Fred began a career as a physician at San Francisco’s Health Center 1, later renamed the Castro-Mission Health Center, which became an epicenter for treating San Francisco’s AIDS epidemic. Despite unknown risks of working with the then-unresearched virus, Fred had his family’s support to work tirelessly in San Francisco and at the GMHC with people affected by HIV at a time when survival was a long shot. Fred continued to serve people living with HIV throughout his career with the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

In the 1980s Fred and several GMHC volunteers formed a private clinic to treat cases of genital warts that were too complex and time consuming to address at the BFC. The wart clinic operated for a number of years in the off hours at a women’s health center in Oakland, turning no patients away for lack of funds.

Fred supported the world’s first queer sperm bank, where he served as Medical Director. The program allowed gay donors and lesbian recipients to access sperm bank services they couldn’t access elsewhere. For many years, Fred was also Medical Director at the BFC, and after retiring from the SFDPH, he continued to maintain his medical license to serve as a physician for the Berkeley Free Clinic.

When Fred retired from the Castro-Mission Health Center in 2013, one of his patients described him as an “AIDS hero” who not only championed non-judgmental health care but did so with compassion and respect. “Fred never pushed me to get on an AIDS cocktail until I had good medical reasons to do so, welcomed me bringing written questions to and taking notes during consultations, saw the value in alternative healing methods including acupuncture and Reiki, and was a true partner in my health care delivery.”

In retirement, Fred continued to help with the rollout of the electronic medical records system for the SFDPH, and got certified as a tax preparer so that he could directly help low-income individuals and families access free tax assistance.

Fred was diagnosed with carcinoid cancer in 2001, and received treatment in the form of numerous surgeries and experimental radiation therapies. By the time his cancer became terminal in 2020, he had fought it for 20 years. Near the end of his life, Fred fought to get an expensive cancer drug, Sandostatin, cleared for palliative use so that people in hospice could access it to alleviate their symptoms and improve comfort and quality of life. The day before he died, he and his wife, Mary, got a call to say their efforts had paid off, and that others on hospice going forward will be able to access the medication through their insurance or through a compassionate access program established by the manufacturer.

Fred had two children, Tessa and Jesse, with his first wife, Lili Shidlovski. As a proud and loving Zeyde (grandfather in Yiddish), Fred and his second wife, Mary Dermody, enjoyed time with Tessa and her wife Micaela Reinstein’s twins, Ever and Jude. Fred was the stepfather to Mary’s daughter, Mirae. Fred loved to sing with his friends in the Anything Goes Chorus, to hike in the East Bay Regional Parks, and to garden. In his last year, he watched TV shows and comedy from his childhood and frequently requested the Jewish comfort foods of his youth – raisin challah and matzo ball soup. He died in his home, dressed in a tie-dye t-shirt, surrounded by family. If people are interested in honoring Fred, the family encourages them to make a donation to the Berkeley Free Clinic and note that it is to support the work of the Gay Men’s Health Collective.