It all started because Bob Schwartz was done with the status quo.

The year was 1976, and he was working as a medical records transcriber at the University of Virginia Hospital, playing softball every chance he got and living in a commune south of Batesville.

His life was a good one, he said, but “I was tired of feeling like all I had to contribute to gay rights was five bucks for the American Civil Liberties Union and an occasionally well-worded letter to the editor,” Schwartz recalled.

So Schwartz decided to become a lawyer, and entered the University of Virginia School of Law a few months after a Newport News native named Clarence Cain graduated. They never met, but both of their lives would go on to affect the experiences of thousands of LGBTQ law students and lawyers, with ripples arguably touching millions of Americans.

The Early Days

In those early fall days on the softball diamond and at “Café du Nord,” as they called the North Grounds eatery, Schwartz made a decision that was simple, elegant and impactful: He would just be himself.

“I didn’t walk around wearing a gay T-shirt or anything, but my rule of thumb was ‘tell no lies,’” he said. “If you ask me a direct question, you’re going to get a straight answer.”

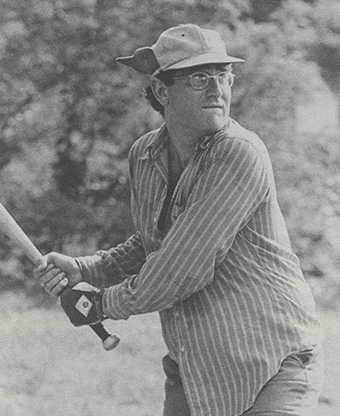

Bob Schwartz ’80, pictured in the Virginia Law Weekly

Schwartz chuckled at the double meaning. He knew his conversational style is the only straight thing about him.

He knew he couldn’t be the only queer law student at UVA but, in the absence of an organized student group, it wasn’t exactly easy to pick out his fellow “friends of Dorothy,” a coded moniker that closeted gay people used then — and sometimes now — to signal their kinship.

For fellowship, Schwartz turned instead to the undergraduate Gay Student Union, which would occasionally throw a dance or a party that was open to the Charlottesville community. During his second year, the group nearly folded because its president had embezzled the entire contents of its coffers to pay his tuition after his parents cut him off when he came out.

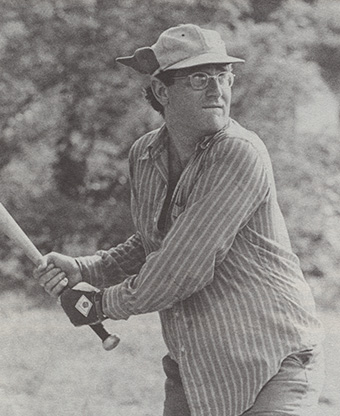

Schwartz tapped another gay law student, John M. Curtin ’81, and together they rescued the GSU by throwing a popular $3 dance every weekend to pay off the organization’s existing debt.

John M. Curtin ’81

Under Schwartz and Curtin, the group also extended a speaking invitation to a personal hero, gay rights activist Frank Kameny, who just a few years earlier had convinced the American Psychiatric Association to stop classifying homosexuality as a mental disorder.

Kameny had lost his job and his national security clearance in 1957 for being gay, and he spent the rest of his life denouncing the evils of the closet. Like Kameny, Schwartz believed visibility was the “key to everything,” from securing basic civil rights to eventual marriage equality.

To that end, Schwartz, Curtin and GSU members took a bucket of bright orange paint out to the Beta Bridge and furtively painted their favorite part of the Good Ol’ Song lyrics: “We come from old Virginia, where all is bright and GAY!”

“Fraternities were out there within 30 minutes, painting over everything we had done,” Schwartz said.

Although his grades got him onto Law Review, Schwartz dropped off to focus on courting a young man named Richard Robinson. Schwartz wore drag to one Law School class dinner and brought Robinson, who dressed as an Arabian princess. Richard also accompanied Robinson to summer associate events at his Big Law firm in Los Angeles. For better or worse, the firm did not extend Schwartz a permanent job offer at the end of the summer — an experience that was all too common for gay and lesbian law students who peeked out of the closet in those days — and Schwartz instead went to work as a staff attorney at the Tidewater Legal Aid Society after graduation. Within a few years, he moved to Atlanta to be with Robinson, join a gay softball league and launch his own small law firm with a gay colleague.

Schwartz has no regrets about choosing visibility over his career.

“I was 28 years old — I felt like I had lost a decade of my life — and I wanted to pave the way for the next generation of gay kids so they wouldn’t lose so many years of their lives,” Schwartz said. “I was part of the Class of 1980, but the Class of 1982 got to know me as an out gay man on the softball field, and the Class of 1984 got to know them. These things add up over time.”

The Founding of GALLSA

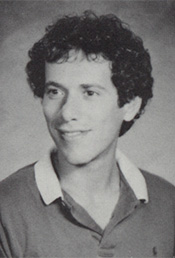

Richard Avidon ’84

Richard Avidon was a member of that Class of 1984. He and his friend Michael Allen ’85 — two cisgender, straight white men, with all of the protection and privilege that affords — were concerned about the climate for out gay people at the Law School in the mid-1980s, at a time when national figures like Jerry Falwell and William Bradford Reynolds were invited to campus to share views that were not friendly to the LGBTQ community.

As a legal and political matter, each step of progress toward civil rights was being met with virulent backlash.

Michael Allen ’85 in law school and today

By 1984, 170 Fortune 500 companies had pledged not to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation — but neither the American Bar Association nor the Law School had yet taken that stand. Only Wisconsin had a state statute banning such discrimination in housing, employment and public accommodations. California had passed a similar law, but the governor vetoed it.

Between 1970 and 1984, around 27 states decriminalized sodomy. Yet in 1982, Atlanta police officers charged Michael Hardwick, a gay man, with violating Georgia’s anti-sodomy law in his own home. Hardwick decided to — quite literally — make a federal case out of it.

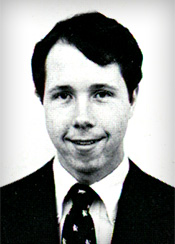

Clarence Cain ’77, pictured in Corks and Curls yearbook as an undergraduate at UVA

Moreover, the HIV/AIDS crisis was just beginning to unfold. Among the millions of lives AIDS would claim, the disease would kill Clarence Cain and John Curtin, plus two of Schwartz’s Law School classmates, his business partner and “well over a hundred” members of his Hotlanta Softball League.

In February of 1984, Avidon and Allen saw a notice in the Virginia Law Weekly announcing the first meeting of the Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association, which would serve as “a support and rights advocacy group.” To this day, they don’t know who placed the notice, but they showed up at the meeting and became the informal heads of GALLSA. To convey his solidarity, Allen often wore a yellow button saying: “How Dare You Presume I’m Straight.”

“These were pretty fraught times,” Allen said. “Our [ally] activism was a way of saying, ‘You’re not alone.’ There were many people who felt marginalized because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or political views. And if we didn’t all band together, we were all gonna sink individually.”

In addition to the typical potlucks and small social events, the group also circulated petitions to advocate for changes at the Law School, and hosted speakers, including Dan Bradley, a Jimmy Carter appointee who resigned as president of the federally sponsored Legal Services Corporation after coming out. (Bradley’s 1984 speech at UVA, as memorialized by the Virginia Law Weekly, provided the contemporaneous statistics cited above. But he also predicted that day that, “In my lifetime, we are going to see all laws discriminating against gay people fall by the wayside.” Bradley died of AIDS four years later.)

By April, a GALLSA petition won the students explicit assurance from the faculty that applicants would not be discriminated against on the basis of sexual orientation, and Dean Richard Merrill added a non-discrimination statement to applications and informational materials.

“We looked at the top 10 law schools at that point, and five or six of them had stated such a non-discrimination policy,” Avidon said. “So we started a petition and sat at a desk to have people sign it. We basically played off people’s desire to be in the top 10 — let’s do what they’re doing.”

Ken Williams ’86 as a law student and today

First-year student Ken Williams sat at some of those tables, attended the potlucks and took over as GALLSA president in 1986. He put that position on his resume.

Under Williams, the group had about 20 members, which included Darden graduate business students and closeted members. During Gay Awareness Week in 1986, Williams told the Virginia Law Weekly that an interviewer called a friend of his to ask whether Williams was gay. He received no offer from that firm.

A Rocky Legal Landscape

Meanwhile, the legal outlook for gay rights at the time was grim.

In the spring of Williams’ third year at UVA Law, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Michael Hardwick’s case. The decision in Bowers v. Hardwick would deal a body-blow to the gay community, holding that there was “no fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy” — steering the question presented away from Hardwick’s broader right to privacy, not to mention the chilling effect the law had on the right of heterosexuals to engage in private acts that could be construed as sodomy.

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. cast the deciding vote in Bowers; in fact, Powell reversed the initial vote he had cast in conference. Powell reportedly said, in a private conference with the justices, that he had never met a homosexual.

Professor Dan Ortiz, a gay Powell clerk in the term before Bowers, contends Powell was probably attempting to politely steer away from a touchy subject.

In fact, Joyce Murdoch and Deb Price, authors of “Courting Justice,” found that Powell had hired one or more gay clerks for six consecutive terms in the 1980s, including Ortiz, who joined the UVA Law faculty after his clerkship and currently runs the school’s Supreme Court Litigation Clinic. Ortiz was not out to Powell.

In his biography of Powell, Professor and former Dean John C. Jeffries Jr. ’73, another Powell clerk, wrote that Powell, in not sticking with his initial vote, “failed to act on his own best judgment” due to a lack of confidence on the issue.

Professor Anne Coughlin, who has advised GALLSA’s successor organizations since she arrived at the Law School in 1995, was a Powell clerk during Bowers. While she calls the Bowers fallout “incredibly painful,” she faults no one for remaining in the closet at that time. (She, like Ortiz, also doubts it would have made a difference.)

“It’s absolutely wonderful for me to hear our students or gay folks express wonderment that people were closeted, but it was not a safe world for [gay] people, professionally, culturally, emotionally,” Coughlin said. “I mean, coming out in that world could be terribly dangerous — particularly in the South.”

Coming Out in the 1990s

By 1990, first-year law student Donna L. Wilson was willing to take her chances on coming out, at least after letting classmates get to know her first.

“I was really lucky, and any lack of acceptance I felt was more external to UVA and just because of the world we were inhabiting at the time,” Wilson said.

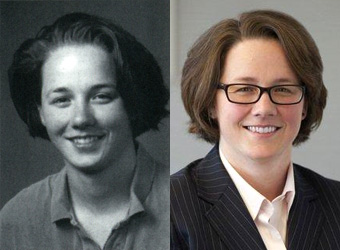

Donna Wilson ’93 in law school and today

In that world, Clarence Cain ’73 had contracted HIV and was fired by his legal services firm in 1987 after he was hospitalized for AIDS-related pneumonia. He won his own federal lawsuit based on Pennsylvania’s state disability law, including punitive damages. But he died in penury in his mother’s Newport News apartment, two months after winning his case in 1990. His story would help inspire the film “Philadelphia,” starring Tom Hanks, who won an Oscar in his role as the plaintiff, and Denzel Washington.

“That world” was the one in which Colorado voters would ultimately approve Amendment 2, which prohibited cities and the state from offering LGBTQ Coloradans any protections from discrimination in any forum. It was also a world in which the “don’t ask, don’t tell” ban on out military servicemembers would soon become law.

“That world” was a terrible legal job market to boot, Wilson noted.

Michael Tate ’92 served as president of GALLSA.

Wilson’s friend Michael Tate ’92 served as president of GALLSA while Wilson was vice president. Both were on Law Review, and Wilson’s student note topic addressed the anti-gay policy of the Boy Scouts of America.

Despite her academic achievements, Wilson was told by one major law firm that she “would be more comfortable somewhere else.” (Wilson needn’t worry. Skadden Arps, where she had worked as a paralegal, gladly took her aboard as an associate.)

Yet when Wilson came out to her Law School softball teammates her first year, they were seemingly unfazed. With one exception: “If you’re a lesbian, why aren’t you a better softball player?” they joked.

A Breakthrough Case

By the spring of 1997, GALLSA had changed its name to BGALLSA to include bisexual students. The concerns of transgender students were not yet fully part of the student organization’s vision. The group had about 15 members, according to its then-co-president, Susan Baker ’98, none of whom were straight allies like Avidon and Allen had been. (Gary Gansle ’98 was also co-president with Baker, as well as president of his first-year class.)

The year before, a 6-3 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court in Romer v. Evans had eviscerated the Colorado anti-gay amendment, with Justice Anthony Kennedy writing that “the Constitution ‘neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.’”

However, the Bowers decision on sodomy laws and the military ban still stood. Moreover, the federal Defense of Marriage Act passed Congress in 1996, barring federal recognition of same-sex marriages.

BGALLSA helped host events and speakers, such as Michelle Benecke, co-founder of Servicemembers Legal Defense Network. Future Solicitor General Ted Olson and UVA Law Professor Mary Anne Case debated whether the Virginia Military Institute should continue to receive state funding in light of its single-sex education model. Legal scholar Michael Seidman visited as a Hardy Cross Dillard lecturer to offer his interpretation of the Romer decision.

The group hosted a pizza party and movie night for National Coming Out Day. With a wink at the topic, if you wanted to attend, you needed to find the group’s bake sale table and ask for the event’s secret location.

Susan Baker ’98 in law school, now Susan Baker Manning

Baker became Susan Baker Manning after marrying her lifelong partner, Katharine Manning ’00, who was two years behind her at the school and a fellow member of BGALLSA. Full legal marriage seemed to be not even a remote possibility at the time.

“I did not think that same-sex marriage was likely any time soon,” Manning said. “But we would have had kids no matter what the government had to say about our relationship.”

In a quirk of history, the two were first legally married in 2004, when San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom decided to damn the torpedoes and issued marriage licenses to 4,000 same-sex couples while a court declined to intervene for nearly a month.

The backlash was both swift and furious. Barely a year had passed since the Supreme Court had overturned its own Bowers decision through Lawrence v. Texas. Now, a month after Newsom’s move, the California Supreme Court halted the San Francisco weddings and later nullified those marriages, including the Baker-Manning nuptials.

California voters then passed a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage in 2008, in the same election in which they voted overwhelmingly to elect the nation’s first Black president.

Manning happened to be sitting in the front row of the Supreme Court on June 26, 2015, one of the last days of the term in which the issue of state same-sex marriage bans came before the court via Obergefell v. Hodges, for which Kennedy was widely expected to be the deciding vote. Clerks were shuffling around and there was a palpable buzz in the courtroom. (One of Kennedy’s clerks at the time was a UVA Law graduate, Andrew Bentz ’12.)

In her pro bono work at Morgan Lewis, Manning coordinated the business community’s efforts to file amicus briefs in the consolidated case. As she had guessed, it turned out to be the day the decision was announced.

“And then Justice Kennedy starts to read the opinion of the Court,” she said.

The cases now before the Court involve other petitioners as well, each with their own experiences. Their stories reveal that they seek not to denigrate marriage but rather to live their lives, or honor their spouses’ memory, joined by its bond.

The ancient origins of marriage confirm its centrality, but it has not stood in isolation from developments in law and society. The history of marriage is one of both continuity and change. That institution — even as confined to opposite-sex relations — has evolved over time.

“Half of the room starts to cry,” Manning said. “This is not your most professional-feeling moment, but there are all these people there that have worked for decades on LGBTQ rights and on marriage in particular — people who are incredibly invested in it, people whose humanity is being affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States — and there are just a lot of sniffles and tears quietly rolling down faces.”

She walked out of the monumental bronze doors of the Supreme Court and stood at the top of the marble steps, which were kept clear by security. “There’s this sea of people and signs and rainbow flags and everything else down on the lower plaza and spilling out into the street,” Manning said. “It was a life and career highlight to see all of that and to experience that rush of joy and relief and validation.”

Opening the Closet Doors

BGALLSA changed its name to Lambda Law Alliance around 2001, according to the Virginia Law Weekly archives. It is no longer difficult to find evidence of the group’s existence or its activities. A search for “Lambda” in the Law Library’s database retrieves 102 results.

The group’s executive board alone comprises 14 students and the group as a whole boasts more than 100 members, including straight allies, according to Chloe Fife ’22, the first openly transgender woman to serve as president.

Chloe Fife ’22

Ten of Fife’s classmates at UVA Law also self-identify as trans, she said, although not all of them do so publicly. Even on the LGB side of the ledger, she said, “We still have at least 10 to 12 people come out every year.”

The Lambda executive board manages the group’s three-pronged mission, which includes a social, community-building element; an advocacy and pro bono element; and a career development program, Fife said.

The advocacy and pro bono work has included pushing for more unisex bathrooms at the Law School, raising money to oppose the state-level anti-trans bills that have popped up around the country, and helping local residents change their legal name and gender.

Virtually all members of today’s Lambda list the organization on their resume, in part to filter out any employers or judges that would not be a good fit, according to Fife and Ruth Payne ’02, the Law School’s senior director of judicial clerkships.

In June 2020, in Bostock v. Clayton County, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is impermissible sex discrimination. Lambda’s own career fair attracts about 20 employers each year, Fife said.

As for the parties? “Hundreds of people show up,” Fife said. “Lambda is definitely known for its ability to throw a good party.”

Postscript

Bob Schwartz, who went by “Elmo” or “E.T. Pelmo” in law school, was inducted into a gay softball Hall of Fame in 2005. He now practices bankruptcy law. Schwartz’s partner, Richard Robinson, died in 1996.

Richard Avidon teaches U.S. history at the Georgetown Day School, while Michael Allen is a partner at the civil rights firm Relman Colfax. He has prosecuted at least three key LGBTQ civil rights cases, including Whitaker v. Kenosha Unified School District No. 1, a 2016 Seventh Circuit case holding that Title IX and the 14th Amendment protect transgender students from discrimination at school.

Turned away from Big Law, Ken Williams went to work as a prosecutor in the New Orleans district attorney’s office and now teaches criminal law at the South Texas College of Law Houston.

Donna Wilson is the CEO and managing partner of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips in Los Angeles. To her knowledge, she is one of two openly gay female managing partners of major U.S. law firms. She says, “I tell associates all the time, the two best pieces of advice are, be curious and be yourself.”

Chloe Fife is studying for the New York bar exam. She will be a securities litigator at Weil, Gotshal & Manges in Manhattan. She will be the only openly trans associate at the firm, but not the first to have worked at Weil.

Susan Baker Manning is a partner and the full-time pro bono trial attorney at Morgan Lewis. She coordinated the business community’s efforts to file amicus briefs in Obergefell v. Hodges, which struck down all same-sex marriage bans. The Mannings have three children. Their son, Elliott, is transgender. “I think it’s got to help on some level that he has queer parents and that there’s a model there for resiliency and affirmatively taking on these issues to try to make the world a little better place around them,” she said. “They understand that you can fight against discrimination, you can achieve things and movements can achieve things over time.”