In my review of the 2018 narrative film “Boy Erased,” based on the 2016 book Boy Erased: A Memoir by Garrard Conley, I wrote that the film “is a starting point for parents wondering what God is asking of them when they discover their child is LGBTQ. First, you love your child unconditionally and go from there. You don’t hurt them, or give them pain and suffering so that ‘good’ [change of sexual orientation] may come of it….

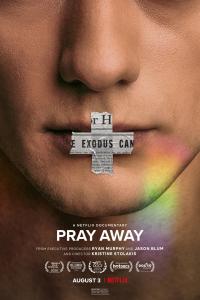

Now director Kristine Stolakis’ documentary “Pray Away” on Netflix revisits the same territory but takes it from the perspective of several people who were at one time part of the conversion or reparative therapy movement.

In 1976 the founders of Exodus International, an organization that would become a mega group and a leader for smaller, autonomous conversion therapy groups, realized that there were gay people who were lost and had nowhere to go. Exodus became the place where they could come for help.

We meet a co-founder of Exodus International, Michael Bussee, a gay man who with others believed that if people who identified themselves as gay or LGBTQ would turn to Jesus, they could re-orient themselves to being heterosexual. John Paulk, a gay young man, joined the group, became ex-gay and a was elected Chairman of the Board of Exodus in 1995. He married an ex-gay woman and had two children. However, after he was seen leaving a gay bar in Washington, DC, he lost his job and eventually admitted that reparative or conversion therapy did not work. He, like Bussee and others, admitted it did often did great harm to people.

Exodus International was dissolved in 2013 because, as Bussee says in the film, their methods of blaming the failings of the same sex parent did not work to reorient a person and in fact, damaged some of those who came to them for help. He has said elsewhere that he has “never met a gay person who became heterosexual because of conversion therapy or ex-gay programs.”

Yvette Cantu Schneider, who after six years as a “practicing lesbian” became a spokesperson for the Exodus and did public policy work for the Family Research Council, is also featured. She began getting panic attacks before speaking engagements and resigned from Exodus and the Family Research Council. She now considers herself bi-sexual and is married with two children. Yvette says that she didn’t know how to make the feelings go away and that the root causes or whether the feelings were right or wrong biblically, didn’t matter anymore. She just knew that if she didn’t go on this journey to discover who she was, she would probably take her own life.

Julie Rogers was raised as a fundamentalist Christian and is also an ex ex-gay person who is featured in the film. She first encountered Living Hope, an associate Exodus ministry that still exists, at the age of 16. She then joined and worked there. Again, bad relationships with parents were blamed for her sexual orientation. When she told Ricky Chelette, the executive director of Living Hope, that she had good relationships with her parents, he told her then her same-sex attraction was probably due to sex abuse. She said she had not been abused and he told her she had probably suppressed it. Recognizing that Living Hope’s methods were based on junk science, she eventually left, realizing that though she loved her faith, her sexual orientation had not changed. Julie still feels called to live the Christian life and in the film her wedding to Amanda Hite is documented.

The film opens and closes, however, with a young man named Jeffrey McCall. He organizes marches for ex LGBTQ people and does sidewalk ministry by offering to pray for and with people and share his story. He had lived a gay and transgender life but “When I found Jesus,” he explains to a couple, “I felt someone really loved me and called me to share my story.”

“Pray Away” witnesses to the inner struggles of LGBTQ people who want to be Christian and true to who they are as human beings. While the evils of conversion or reparative therapy are not expressed in detail, references to suicide are clear. Practioners of conversion therapy are considered, such as the late Dr. Joseph Nicolosi, who taught that gay feelings could be replaced with heterosexual desires. Success stories are hard to find.

The film does not deal with Catholic reaching or therapeutic experiences specifically. A May 13, 2021 article in America Magazine by Eve Tushnet, however, does: Conversion therapy is still happening in Catholic spaces — and its effects on L.G.B.T. people can be devastating.

Interestingly, both the film “Pray Away” and this article reach the same conclusion. That even if groups or psychologists whose Christian, Catholic (or Jewish as Tushnet mentions) practice is for people with same-sex attraction, they don’t help you with what your future might look like if you do not change your orientation, that therapy and counseling are based on the idea that being gay is based in childhood trauma, that being LGBTQ is a sickness, something to be healed from and the consequences of pornography.

One man that Tushnet interviewed said that the Theology of the Body Institute in Tallahassee, FL does not practice orientation-change therapy, but he discovered that in counseling and confession the Institute still sees the roots of being gay are a result of “wounding that happened in my formation.” Tushnet also talks about the chastity promoting organization Courage for those who experience same-sex attraction. While the organization does not promote conversion therapy, in a couple of the video testimonies on the Courage website that I watched, family of origin trauma is considered a cause of or element in same-sex attraction. Tushnet’s article outlines how Catholic thinking helped create this premise that continues to be used by conversion therapy organizations and practitioners.

So far, 20 US states and Washington DC have banned conversion therapy for minors and DC also bans it for adults.

As a film, I found “Pray Away” intriguing; it is like a feature article in a magazine filled with pictures and personal stories. It made me stop and ask what the options are for LGBTQ believers who want to love God but are not helped by clergy or often untrained “professionals” who focus on behavior rather than the person’s feelings and who think you can “will away” or “pray away” one’s sexual orientation when in actuality the person is born that way. I was inspired by the people who choose to live rather than take their own lives when conversion therapy did not make sense. I was moved by those who said that they loved Jesus, and believed that Jesus loved them – that same Jesus who had once disapproved of them and made them feel cast from the church welcomed them to the church – that they long for.

There is no mention of civil unions for gay couples and gay marriage in the Episcopal church at least, is embraced.

The message of the film is four-fold: conversion or reparative therapy is a harmful, even deadly failure; God loves you as you are; you were made in God’s image and you were born this way; and there is a theology that includes you as a gay person in Christian churches, and it continues to struggle for authentic articulation.

Bussee says at the end of the film that “As long as homophobia exists in this world some form of Exodus [International] will emerge because its underlying belief is that there is something intrinsically disoriented and change-worthy about being gay.”

Youth who undergo conversion therapy, the film says at the end, are twice as likely to attempt suicide. This shocking statistic is a call to love everyone, and act lovingly to all, because we are all made in the image of God. We know this is true.

“What, then, must we do?” Luke 3:10