The first headline about AIDS in The San Francisco Chronicle, published on June 6, 1981, was anything but a warning siren for the pain and death that was on the horizon. The story beneath it was just nine paragraphs with no byline — on a page dominated by a large photo of the Gay Men’s Chorus and a bright feature about their upcoming road trip.

Most of the smiling men on the left of the page would later die of the condition described on the right. And within weeks of the first mention of the “mysterious disease” in the paper, San Francisco would find itself in the epicenter of an epidemic that would reveal local courage, expose national negligence and redefine the city.

With the return of World AIDS Day on December 1, Chronicle photo editor Ash Adams has curated some of the most striking photography from the era. The photos and news coverage from the time show a city that often felt isolated in the fight. After that first article ran in 1981, President Ronald Reagan wouldn’t speak of the epidemic by name on the national stage for another six years.

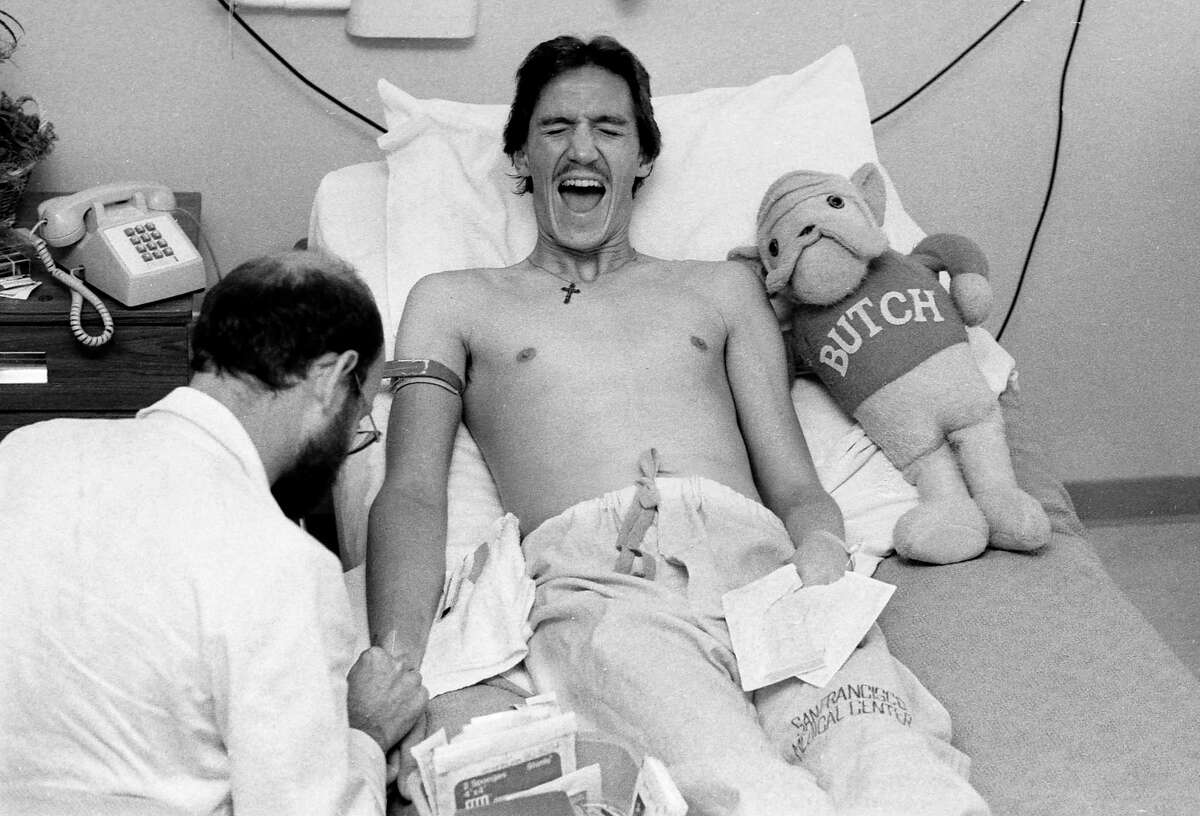

Bruce Schneider, an AIDS patient at San Francisco General Hospital’s AIDS ward 5B, is poked with an IV needle after being admitted with pneumocystis, a fungal infection of the lungs, Nov. 28, 1983.

Steve Ringman / The Chronicle

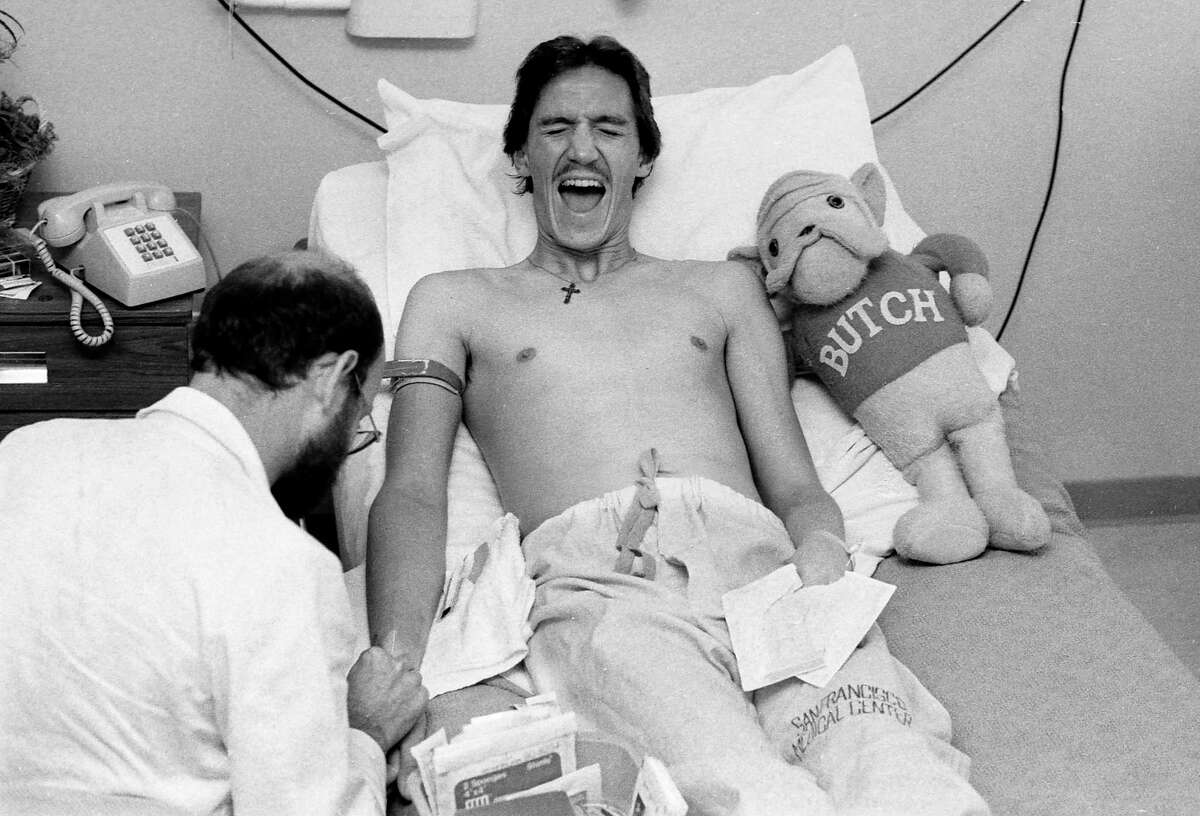

Gay activists marched from San Francisco to the Burroughs-Wellcome Pharmaceuticals warehouse in Burlingame to protest high prices for the AIDS drug AZT. Here activists scale a ladder on to the roof of the building. 01/25/1988 Gay Rights Project

Tom Levy, Staff / The Chronicle

Tubex Injector system – syringe designed to prevent needle sticks among health care workers at risk of contracting HIV, the AIDS virus. San Francisco General Hospital 02/11/1988 Gay Rights Project

Jerry Telfer, Staff / The ChronicleTop: Gay activists marched from San Francisco to the Burroughs-Wellcome Pharmaceuticals warehouse in Burlingame and scaled a ladder onto the roof of the building to protest high prices for the AIDS drug AZT, January 25, 1988. Above: The Tubex Injector system syringe designed to prevent needle sticks among health care workers at risk of contracting HIV. Tom Levy, Jerry Telfer / The Chronicle

AIDS technician Joni Shimabukuro conducts research at UCSF, Dec. 14, 1984.

Gary Fong, Staff / The Chronicle

There was no word for AIDS in the beginning. During those first summer months in 1981, it was a mystery, misdefined as a “gay plague.” The acronym GRID (gay-related immunodeficiency disease) preceded AIDS — until late 1981, when hemophiliacs became ill and a baby contracted the virus from blood transfusions.

San Francisco, too overwhelmed to think politically, became a city of desperation and resourcefulness. Dr. Paul Volberding, hired by San Francisco General Hospital in 1981 as a cancer specialist, saw an AIDS patient during his first day on the job, and ran the hospital’s AIDS clinic from 1983 to 2001.

The city’s epidemiologist Selma Dritz in those first weeks mapped the spread of AIDS on a chalkboard, using patients’ initials and lines to link intimate contact between the afflicted, looking for clues about transmission.

“If you think only scientifically, AIDS is the medical whodunnit of the decade,” Dritz told The Chronicle in 1982. “But who can think that way when it’s going on all around you? When right here in this office I interview two young patients only a week ago, and today I know they are dead?”

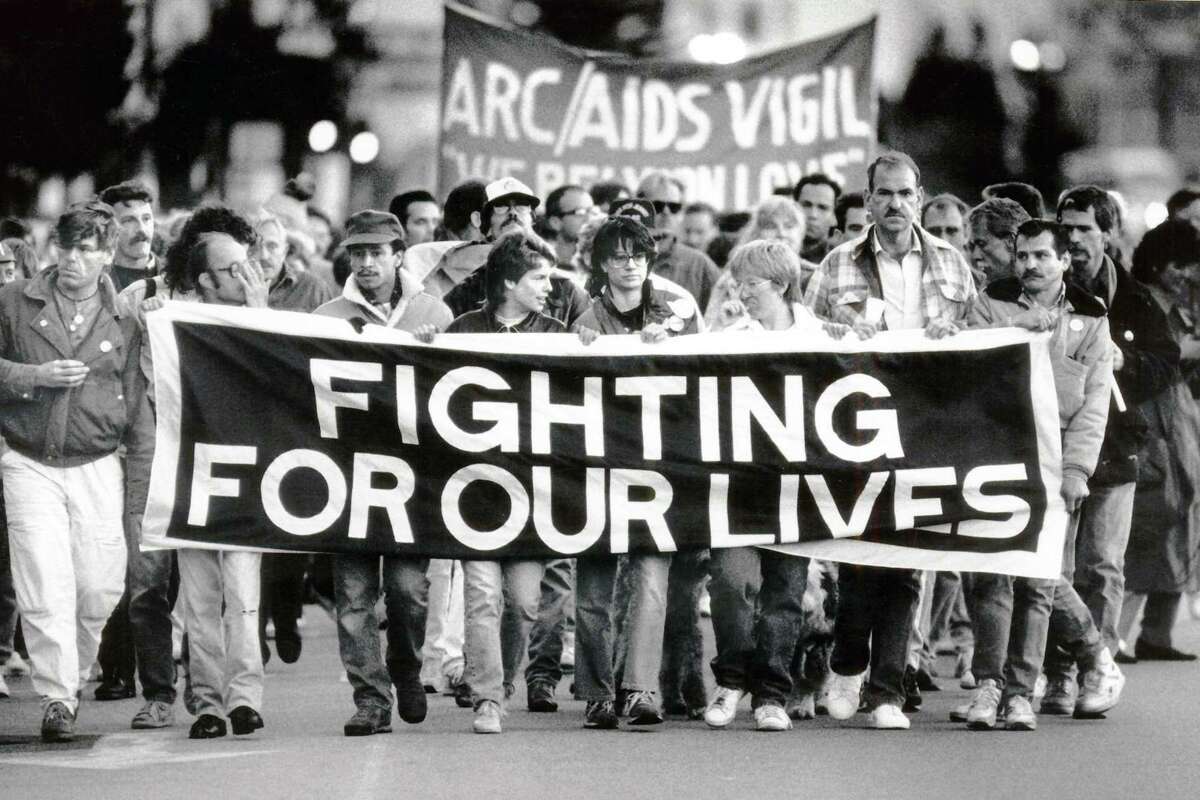

A candlelight protest and vigil for AIDS awareness down Market Street in San Francisco.

Steve Ringman / San Francisco Chronicle

Moments of triage and activism would define the fight against AIDS in San Francisco.

San Francisco General Hospital quickly set up Ward 86, the first AIDS clinic in the nation, where some of the community’s healthiest young men checked in with signs of pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma and never left — casualties in the growing war against the unknown.

Doctors and nurses worked the ward when disease transmission was still unclear. Volberding would later tell The Chronicle of his relief when the first blood test to detect AIDS (developed by San Francisco’s Dr. Dan Levy) was released in 1983, and he tested negative.

Caregivers became friends, and friends became family, as gestures of love and mourning were seen in vigils for the dying in AIDS wards and candlelit tributes on the steps of the City Hall and the Department of Public Health.

The AIDS Vigil, which began in October 1985 when two men with AIDS chained themselves to the doors of the Federal Building at U.N. Plaza to protest government inaction, pictured October 27, 1987. The vigil would last 10 years before a severe storm banished the final two inhabitants.

Steve Ringman, Staff / The Chronicle

Meanwhile, gay activists displayed courage and resourcefulness in the streets of New York and San Francisco, making noise until an apathetic public could no longer ignore the horrors.

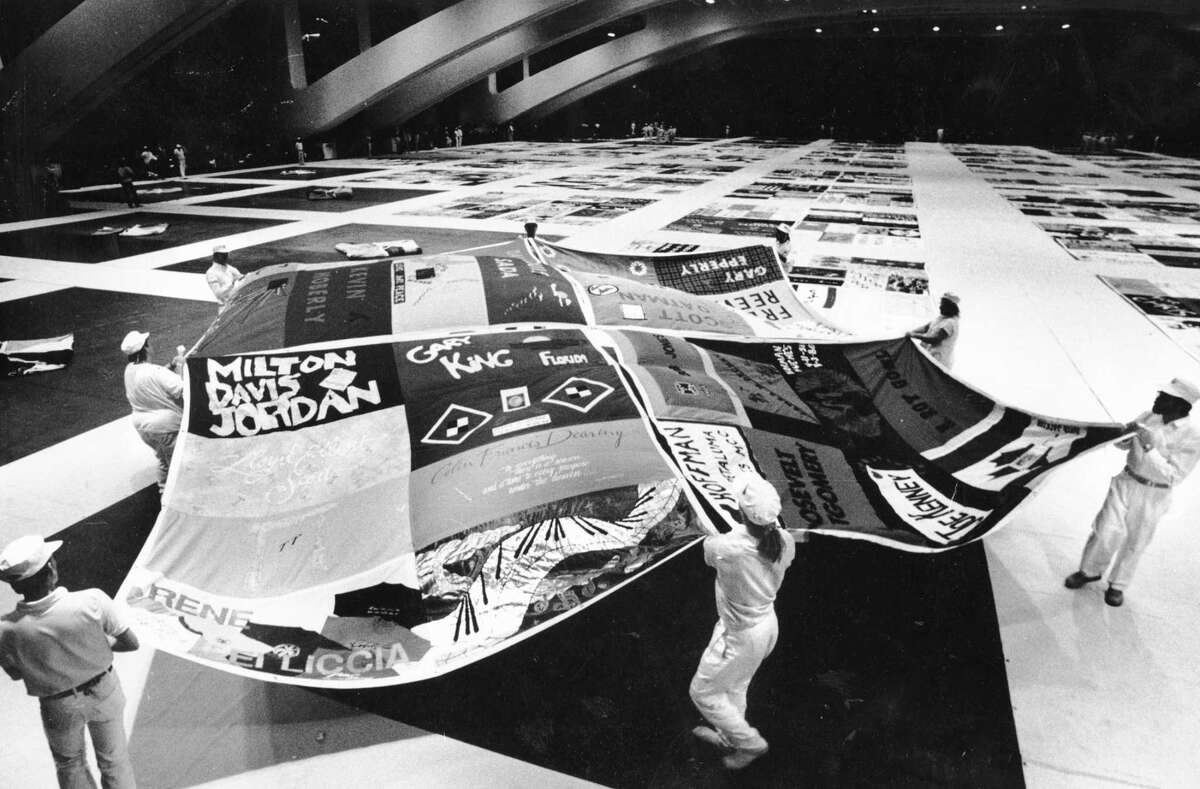

Cleve Jones formed the San Francisco AIDS Foundation in 1982. Jones would later create the first panel of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which remains the most striking blend of folk art and activism in American history.

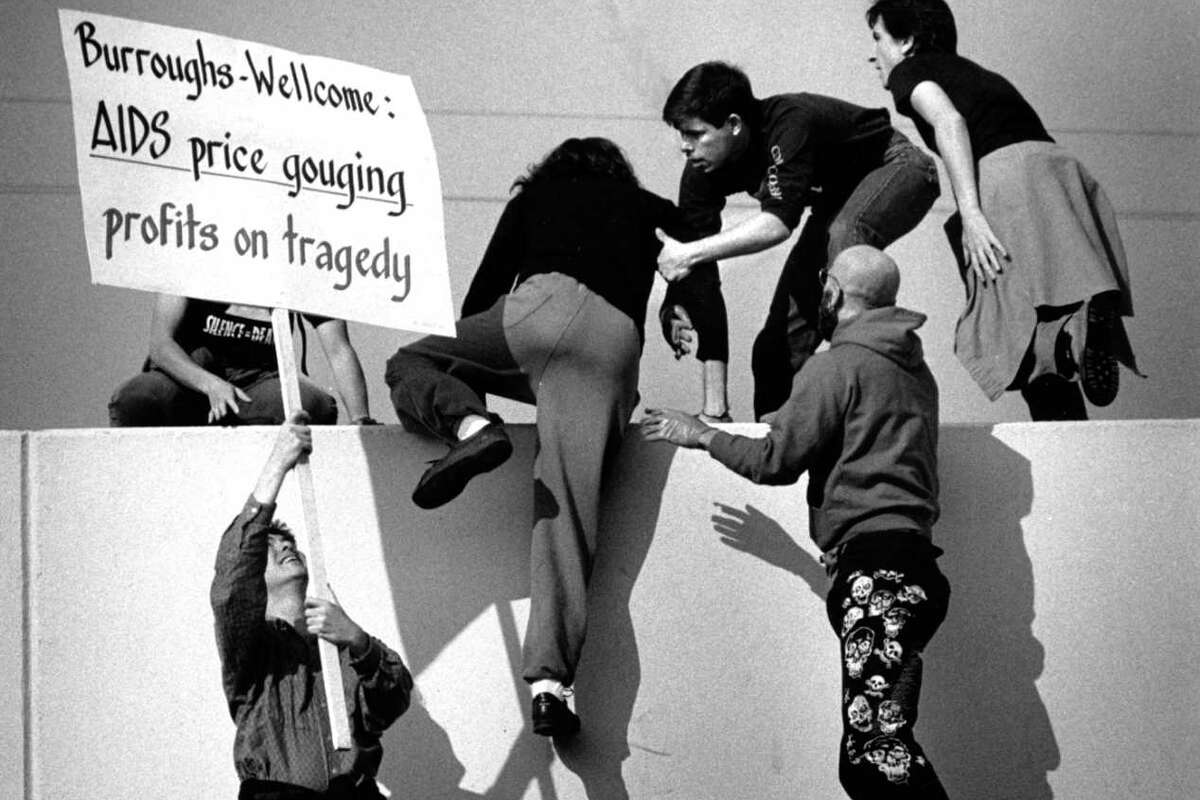

As the nation ignored the tragedies in their community, gay activism became bolder, blocking streets, scaling public buildings and stopping traffic on the Golden Gate Bridge to raise awareness. By June 1990, when the Sixth International Conference on AIDS reached San Francisco, there were multiple demonstrations every day, including a Market Street protest where hundreds laid on the street to bring attention to the 85,000 AIDS casualties at that time.

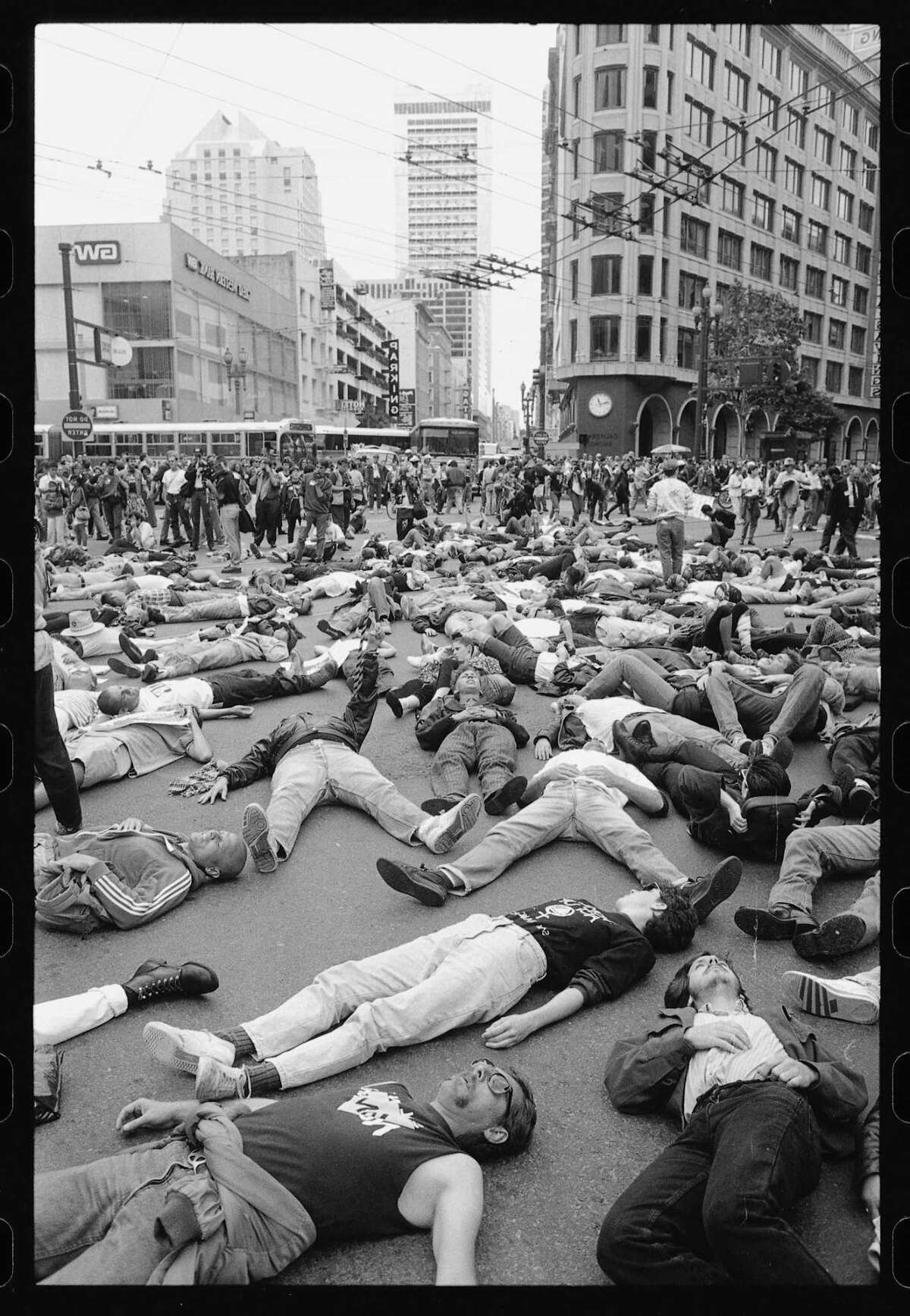

Hundreds laid on Market Street and stopped traffic during the Sixth International Conference in San Francisco to draw attention to the 85,000 AIDS casualties in the United States, June 22, 1990.

Frederic Larson, Photographer

1st ARC/AIDS Vigil at UN Plaza, San Francisco. 1985 Gay Rights Project

Tom Levy, Staff / The Chronicle

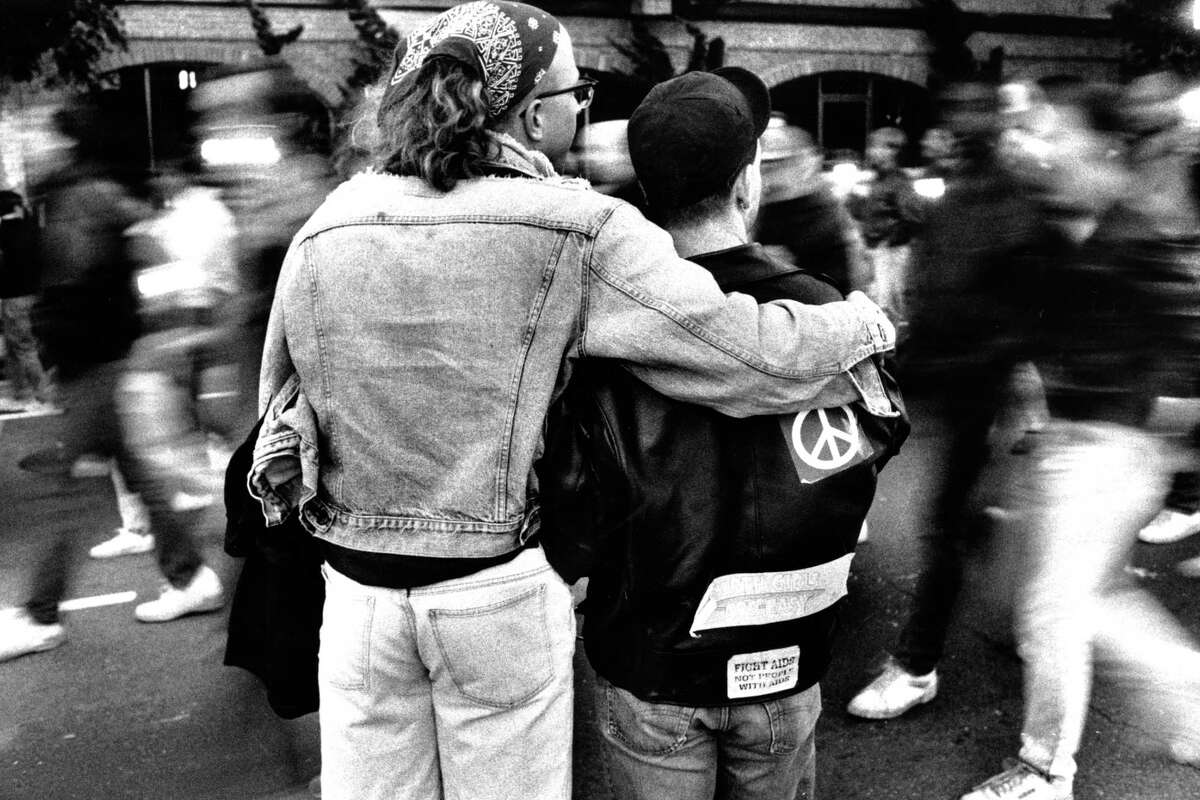

Gay activists marched from San Francisco to the Burroughs-Wellcome Pharmaceuticals warehouse in Burlingame to protest high prices for the AIDS drug AZT. Two men embrace as the march begins in the Castro. 01/25/1988 Gay Rights Project

Scott Sommerdorf, Staff / The ChronicleTop: A protestor at the AIDS Vigil at UN Plaza in San Francisco in 1985. Above: Gay activists marched from the Castro to the Burroughs-Wellcome Pharmaceuticals warehouse in Burlingame to protest high prices for the AIDS drug AZT, January 25, 1988. Tom Levy, Scott Sommerdorf / The Chronicle

One of the most eerie parts of the AIDS crisis, in retrospect, was the five-alarm response by San Francisco, New York and Los Angeles, while the nation wrote the epidemic off as a “gay cancer.” The mistake would cost many thousands of lives.

The Bay Area media quickly identified the weight of the moment. The Chronicle hired Randy Shilts, a bold and crusading reporter who had worked for gay news magazines, to cover the epidemic alongside longtime science editor David Perlman — who wrote that first unbylined AIDS story. KPIX’s Hank Plante was among the early reporters on the beat and KRON documentarian Larry Lee in 1982 produced the Bay Area’s first documentary about AIDS. Chronicle photographers Steve Ringman, Tom Levy and Gary Fong, among others, took pictures in AIDS wards and during protests.

The national newscasts on ABC, CBS and NBC wouldn’t mention AIDS until late in 1982.

ACT UP protestors are arrested at the Sixth International AIDS Conference at Moscone Center in San Francisco in June 1990.

Vince Maggiora, Staff / The Chronicle

San Francisco seemed to be alone for the first five years of the fight. Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s proposed AIDS budget for San Francisco in 1983 was reportedly bigger than Reagan’s AIDS-fighting budget for the entire nation.

By the time Reagan finally spoke of the pandemic publicly on May 31, 1987, more than 21,000 Americans had died.

Dr. William Owen examines Fred Hoffman at St. Lukes Hospital in San Francisco while Hoffman’s lover, Russ Fields, provides moral support, July 20, 1987.

Tom Levy, Staff / The Chronicle

A stronger national push for treatments arrived late in the 1980s, as activists and epidemiologists at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention began to see their common ground.

The FDA approved the promising AIDS treatment AZT in 1987, but high prices prompted more high-profile activism and the formation of the group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. ACT UP in the 1980s and early ’90s demanded patients get a voice in federal decision-making, and in 2022 the group continues its worldwide fight to end AIDS.

Dr. Anthony Fauci’s career bridges two pandemics — AIDS and COVID-19. He visited San Francisco for an AIDS conference in 1990, after he was changed by a meeting with Terry Sutton, a San Francisco teacher who was taking a drug that was making him blind, while a similar drug with less dire side effects was stuck behind government regulations.

“When the history of AIDS in 1989 is written, the transformation of Anthony Fauci may well emerge as one of the most dramatic — and consequential — of human interest stories,” Shilts wrote for The Chronicle that year.

Fauci, who had been the subject of protests in the 1980s, became friends and allies with activists from ACT UP and other organizations —breaking ranks with the FDA and encouraging federal officials to speed up testing and approval for drugs that treat life-threatening diseases.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, created by activist Cleve Jones, opening at the Moscone Center on December 17, 1987 after debuting on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. during the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

Fred Larson / The Chronicle

Above: Activists march on Market Street in 1988, the year a presidential report noted that only 10 percent of those infected with HIV could hope to live beyond five years. AIDS25_PH10.jpg May 30, 1988 – Marchers made their way down Market Street towards City Hall proclaiming their continued battle against AIDS. The huge crowd took over this sidewalk and part of the street and marched behind this large banner. Brant Ward/ San Francisco Chronicle/ file photo 1988— Sent 07/24/12 13:03:04 as forum25_sirica_PH with caption:

Brant Ward, STAFF / San Francisco Chronicle/ file ph

AIDS protest Gay activists including ACT-UP protest the filming of television show “Midnight Caller” episode “After It Happened” which depicts a bisexual man deliberately infecting victims with the HIV virus. Gay Rights Project

Tom Levy, Staff / The ChronicleTop: Activists march on Market Street in 1988, the year a presidential report noted that only 10% of those infected with HIV could hope to live beyond five years. Above: Gay activists including ACT UP members protest the filming of television show “Midnight Caller,” which depicted a bisexual man deliberately infecting victims with the HIV virus. Brant Ward, Tom Levy / The Chronicle

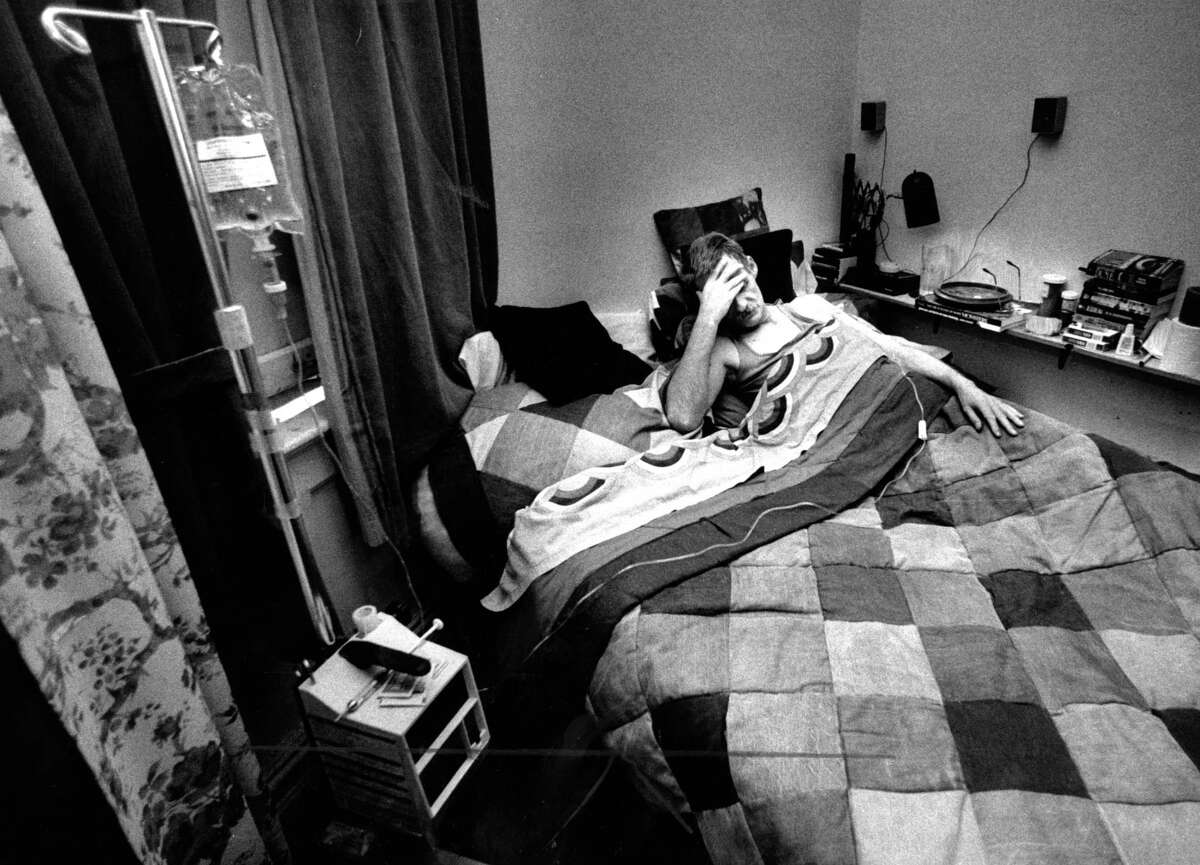

AIDS patient Chris Cummins in his room at the Folsom Street Hotel, hooked up to a machine dispensing Amphotericin and Heparin, September 4, 1987.

Deanne Fitzmaurice, Staff / The Chronicle

By 1992, AIDS deaths surpassed 100,000 in the U.S., and by 1994 more than 10,000 had died in San Francisco. Chronicle reporter Shilts was among that number; he died in 1994.

Progress was incremental, but undeniable.

There’s still no cure for AIDS, but the efforts of scientists and activists have allowed a growing number of the afflicted to live long, full lives with the disease.

“We brought out the best in America by kicking and screaming and prodding,” activist Hank Wilson told The Chronicle in 2006. “When I look today about how people responded, I look with gratitude and calmness.”

Peter Hartlaub (he/him) is The San Francisco Chronicle culture critic Email: phartlaub@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @PeterHartlaub