On the new season of In Treatment, John Benjamin Hickey’s character, Colin, arrives for therapy at Uzo Aduba’s luxurious Los Angeles home just out of jail and desperate to charm her. Colin, arrested for financial crimes, has recently been released because of COVID, but he tries to insist to Aduba’s therapist Brooke that he isn’t that bad a guy really. He’s liberal, he says, and a former Santa Monica beach bum. He gets it.

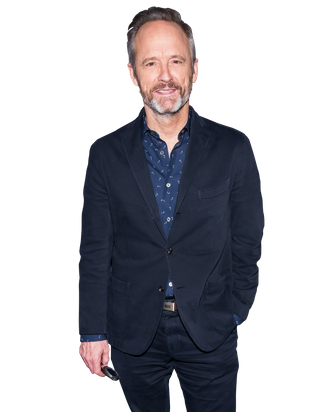

As the sessions progress, it’s very clear Colin doesn’t get it, that he frequently says racist, sexist, and generally awful things when he gets defensive but clings to the idea that he’s a good guy. To Hickey, a longtime stage and screen actor who relished In Treatment’s playlike extended scenes, the gulf between how Colin sees himself and his actions was what made him fun to play — and also led Hickey to examine the parts of himself that could relate to the character. Speaking with Vulture over the phone, Hickey discussed shooting during COVID, Broadway’s shutdown, and his streak of playing white cis men who try to let themselves off the hook.

Where do you start with a character like Colin? Did you research financial crime?

It was much less about researching the person because, week after week, I’d read a script and be like, Holy shit, that’s who he is. That’s what he’s been lying about. It was peeling back layers of an onion. The writers had finished all of the scripts, and they said to me that they think it’s better if you live in the moment and believe what Colin is saying in the moment. So I would get a script and learn the whole thing in the six or seven days I would have between episodes. I spent days walking my dogs around Nichols Canyon with the script in my hand saying my lines out loud. People thought I was as crazy as my character.

So many of these scenes are about him trying to position himself as a good person, and Brooke not letting him off the hook.

All of the things that make him misogynistic, racist, homophobic — all the things we can associate with the patriarchy — come out in these unconscious ways. The thing the writers did cleverly is that Colin’s not a stereotypical straight white cis man. He considers himself a very hip, liberal guy. I have to say that makes it fun to play because if he was just an evil corporate criminal, it wouldn’t have been nearly as interesting.

What makes that fun to play?

Well, it’s always fun to play somebody who’s deeply flawed, in the same way it’s fun to play Richard III. What was so interesting about the fact that it’s Uzo playing Brooke, and that she is a woman of color, was that those are all things Colin thinks he has empathy for. But he objectifies people, and especially women. I found it interesting to play that dynamic with Uzo. I consider myself a pretty woke guy, but even with Colin things would come out and I would be like, This is horrifying, but I understand where it comes from, and it opens up a conversation. There were conversations between me and Uzo and me and the directors, most of whom were female and people of color.

What were those conversations like?

Because it was in the context of acting and playing make-believe, we could talk about things that pissed us off, that we made generalizations about, and channel it into those people. It was a safe space to play an unsafe guy. At the end of the day, we were all like, “Jesus, Colin says and does the most hateful things, and yet I kind of like the guy?” He’s a lovable narcissist.

Well, you have to understand how he’s gotten so far on his charm for the character to work.

He’s doing the thing that a lot of people try to do with their therapist. I thought back to when I started therapy when I was in my late 20s in New York. I remember so much of what I was trying to do for the longest time was make her like me. It’s when you run out of toys and tactics with which to impress them — that’s when the real work begins. We get there with Colin by the end of it. No spoilers, but it’s a very different ending than you would expect.

Did filming the show during COVID affect how you had to approach your scenes?

When they sent me the email about doing it, they said that because of what In Treatment is, it was a “COVID-logical show.” She’s sitting there. I’m sitting here. We happen to be six feet apart. Other than the masks and goggles we wore, and the amount of testing that we did, and all the other protocols, it didn’t feel that much different than anything else I’ve worked on.

I had COVID a year ago. I was about to go into previews for the play I was directing and they shut us down. I went straight from the meeting on March 12 to my doctor’s and I tested positive and had a really bad few weeks. I completely recovered, happy to say, but I’d always felt a bit of a fog in my brain. So this show presented a real challenge to me. My brain was getting a fucking post-COVID workout because I had so many lines to learn. And then Uzo and I would both be shot out of a cannon because we had two days to film the thing.

So it was two days for each of those episodes?

They would shoot all my coverage in one day and all of her coverage another day. Twenty-eight pages of dialogue in one day, so … it was intense. You had to make sure you ate a good amount of almonds and protein bars. Don’t get too caffeinated. Pace yourself.

Watching the show, I thought there was something similar between Colin and Henry Wilcox, the character you played on Broadway in The Inheritance. He’s a wealthy, conservative, older gay man who can’t see himself as anything but good.

I hadn’t thought about it, but they are similar in that they’ve made a deal with the devil. Henry’s climbed a ladder of success as a gay man in New York — a gay Republican, that oxymoron — but mainly as a denier of the calamity of what happened to his generation [AIDS] — until this young man raises him up and makes him realize you’re supposed to forgive yourself and each other. Colin is a major denier, too, about his past. I wouldn’t describe Henry as pathological, though. Henry’s just a fucked-up guy. Colin makes him look like a walk on the beach.

Both those characters are near the center of patriarchal institutions but let themselves off the hook, in a way, by going, Oh, well, I’m gay, or Oh, well, I’m liberal. They resist reckoning further. Is there something interesting to you in a character in that position?

Absolutely, because you recognize it in yourself. I came to New York in 1983 as a young gay man. I came out and was my authentic self. When you are an outsider in some senses, when you look at the patriarchy, you don’t recognize the parts of yourself that are in it. There are some things that are so comfortable about my life that I’d never been aware of. Because I was a gay man, I thought I was a minority, but I was part of a power structure I greatly benefited from. I thought there was a commonality between all LGBTQ people. And there isn’t. We contain multitudes. You have to acknowledge that your experience is not the same as anyone else’s. And a lot of that was happening with The Inheritance as well. Matthew López, a writer of color, wrote a story with Black characters and white characters. As we started that play in London three or four years ago, the world started changing, and the conversations in the room started changing.

One of the criticisms of the play was its focus on a set of primarily white main characters. How did you respond to that?

We had an extraordinary journey with the play. It had its ups and downs, and as the world changed, the lens through which it was being watched changed, and some of it became controversial. I understood that and accepted it. But I always went back to what Matthew’s initial impulse was, and mainly that was this wonderful cross-generational thing and an adaptation of Howards End. Matthew was more articulate about where we started and where we ended and what he was trying to do. But I think what’s so exciting about being Matthew López, or being Jeremy O. Harris, is what they do next, as far as representation goes.

The Hollywood Reporter recently published its cover story on Scott Rudin [Editor’s note: This interview was conducted the week after THR published its expose]. He was a producer on The Inheritance, so I was wondering what your reaction was to that piece?

I’ve only ever had a few encounters with Scott. All I can say is that my encounters have been good. That kind of behavior in the workplace I have not been witness to, so I can’t speak to it, but of course it’s intolerable and inexcusable. By the same token, I think that we need as much strength in the theater now as we possibly can get. I’m aware of what an extraordinary producer of the theater he is. I hope we can all move forward and learn and bring the theater back to life.

You were set to direct Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker in Plaza Suite just before Broadway shut down. Do you have plans for that to return?

I think I can safely speak for them in that they are 1,000 percent determined they will be back sooner rather than later. Exactly when that is I’m not sure, but none of us are. We have little Zoom parties every now and then just to touch base. I see them occasionally and go, “Let’s just run the first scene back.” I remember when they were in their final dress rehearsal in hair and makeup. We all knew it was coming. I remember looking at them onstage and thinking it was like that quartet on the Titanic. We were hitting an iceberg.

You’re also in this movie Sublet, where you play a gay New York writer visiting Tel Aviv who has a series of encounters with a younger man. In a way, he’s closest of the people we’ve talked about to your own story.

It’s funny because the parts I’ve gotten to play, especially in the theater, have been gay parts that were very much a reflection of the times. In Sublet, I got to explore this guy who lived through the epidemic and survived it and is happily married but feels in some ways like a ghost — the irony being that he lost so many friends. He’s a travel writer, and he meets this young man who’s just discovering his sexuality, and through that young person’s eyes he sees the city in a way he’d never have seen it. It’s a voyage of discovery.

It’s a beautiful thing for me as a gay man to play a character who is my age, who is a New Yorker. He’s different from myself, but it’s reflective of a lot of gay men who are my age, seeing what’s going on in the world. Feeling like, Wow, I survived. I’m so happy I survived, and look what I’ve survived to see — and has something passed me by? Now that we can do all this, who are we? What is the gay identity? So many people are asking that question right now.