In December, my husband, our 5-year-old daughter and I tested positive for COVID-19. Life, already off-kilter, lurched. Smell, taste, breath — were they normal? The air smelled only of cold; everything tasted vaguely of cardboard.

The state mailed us a pulse oximeter to read oxygen levels from our fingers. The device beeped when those levels dipped too low — a seemingly objective measure during a subjective time. We used the device with abandon, only my husband regularly triggering the alarm. He went to bed, where he stayed for days, or maybe it was weeks. Time distilled into moments: remote school, meals, Christmas, pulse-ox, beep.

We exited quarantine on January 1, the day of fresh starts. Except my once energetic 8-year-old son, who somehow never tested positive, now loafed in front of the heater for hours. My husband, his breathing still abnormal and his fatigue lingering, raged. Ever the extrovert, I absorbed their emotions as my own. My risk calculation shifted, as despair overshadowed the fear of disease. The sickness we had hid from for so long had found us anyway. Were we now immune? Should we proceed just as before?

Prior to the sickness, I’d been researching pandemic fatigue, a term used to describe the boredom that can arise during a protracted crisis like the one we’re in now (SN Online: 2/15/21). “People prefer action to inaction,” social psychologist Erin Westgate of the University of Florida in Gainesville told me. For some, that compulsion toward the experiential runs deep, she and colleagues reported in 2014 in Science. When the researchers gave college students a choice between sitting idly in a quiet room or pushing a button to receive an electric shock, a startling number went for the shock.

I have been seeking, and pushing, that button all my life. I’ve taught English in Japan, worked as a national park ranger and, following an unfortunate series of events, sold pineapples along a tourist highway in Hawaii in exchange for a tent over my head. Westgate’s recent work suggests that button pushing sorts often flourish in rich and aesthetic environs. I took heed. Against the dreary backdrop of being homebound in a global health crisis, I signed up for private pottery lessons, drawn viscerally to the idea of creating something from mud.

A third path

Psychologists who study well-being or human flourishing have long posited that the “good life” can be pursued via two paths: happiness or meaning.

“So far, psychologists worked with this dichotomy — a dichotomous model of well-being about life,” says psychologist Shigehiro Oishi. He describes the happy life as one of joy, comfort and security, and the meaningful life as one of significance, purpose and coherence, or order. Happiness and meaning can run parallel or intersect, Oishi says. Both concepts are largely rooted in personal and societal stability.

What happens, though, when the ground beneath one’s feet buckles? Or what if one was never quite stable to begin with? What hope is there for finding a path to the good life?

For the last six years, Oishi and his team at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville have been hammering out their response: a third path to the good life coined “psychological richness.” Their research suggests that the ingredients of a rich life come not from stability in life circumstances or in temperament. Rather, the path to a rich life arises from novelty seeking, curiosity and moments that shift one’s view of the world. Rich experiences are neither inherently good nor bad; they may be intentional or accidental, joyous or traumatic.

The pandemic, in this light, embodies a novel, perspective-changing, psychologically rich moment. It has shattered our routines and livelihoods, robbed us of our loved ones and plunged many into despondency. But it has also steered some of us to the mud. We have captured wild yeast for sourdough breads, planted gardens and knitted sweaters; we have stared at a wet mound of clay on a wheel and wondered, what next?

This third good life path can provide a balm in difficult times, says Westgate, Oishi’s former graduate student. “Psychological richness opens up an avenue to the good life for people for whom circumstances may seem to have cut off paths to happiness and meaning.”

Aristotle’s legacy

If you want to understand psychological richness, read about Oliver Sacks, advises Lorraine Besser, a philosopher at Middlebury College in Vermont and Oishi’s collaborator. She is thinking of an adieu to the world that Sacks wrote in the New York Times in February 2015, shortly after learning he was dying of cancer.

The renowned author and neurologist drew his inspiration from philosopher David Hume, who had written a similar adieu in 1776. Hume described himself as possessing a “mild disposition,” Sacks wrote. “Here I depart from Hume. While I have enjoyed loving relationships and friendships and have no real enmities, I cannot say (nor would anyone who knows me say) that I am a man of mild dispositions. On the contrary, I am a man of vehement disposition, with violent enthusiasms, and extreme immoderation in all my passions.”

Ancient discussions of the good life do not appear to consider Sacks’ model. Instead, fourth century B.C. Greek philosopher Aristotle looms large in this esoteric space. He opens his treatise, Nicomachean Ethics, by reviewing the various contenders for the good life — pleasure, honor, wealth, health or eminence — eventually arriving at “eudaimonia,” essentially human flourishing. The eudaimonic person, Aristotle wrote, “is active in accordance with complete virtue … not for some unspecified period but throughout a complete life.”

Of those contenders, only pleasure and eudaimonia, the “feeling good and being good” sides of that dichotomous coin, have withstood the long test of time, Westgate says.

Aristotle, an unequivocal be-gooder, considered the good life an objective ideal. So does Susan Wolf. “Some philosophers, including me, say a good life isn’t just good from the inside,” says Wolf, a moral philosopher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Instead, a life must also be good from the outside, or from the perspective of one’s community.

But the emergence of positive psychology several decades ago shifted attention from the collective to the individual. Now, Westgate says, “whether or not it’s a good life is really in the eyes of the person who led that life.”

Sacks’ vision

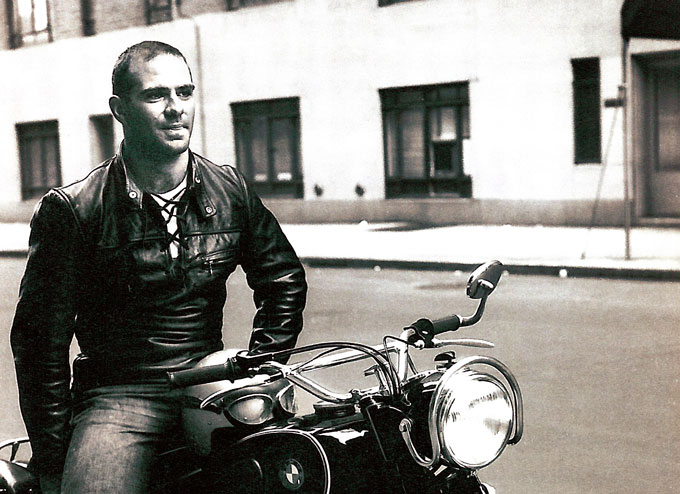

Sacks’ early years were marked by heartache, according to a documentary of his life that aired on PBS in April. Born in 1933 in London, Sacks was sent to a boarding school during World War II, where the other children bullied him and his older brother, Michael. In that environment, Michael became psychotic and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The family was devastated. Then, when Sacks was 18, his parents discovered he was gay. His mother, with whom he shared a close bond, called him an “abomination.”

“Her words haunted me for much of my life and played a major part in inhibiting and injecting with guilt my sense of my own sexuality,” Sacks said.

Sacks fled to San Francisco on his 27th birthday and interned at a medical center. Off hours, Sacks muscled up, eventually lifting a 600-pound bar from a squat to set a California weight lifting record. He also got hooked on amphetamines, thereby sleeping and eating little, while roaring high and fast on his motorcycle. Sacks, the documentary suggests, was running from his own overwhelming loneliness.

“That kind of sensitivity is dangerous. It requires a degree of appetite, vitality, a responsiveness, which means that you could go off the rails at any moment,” the documentary’s director Ric Burns tells me. “The question becomes: What is the relationship you’re going to have to your own appetites?”

On New Year’s Eve 1965, Sacks stared into the abyss of his drug addiction. “I looked at my emaciated face and I said, ‘Oliver, you will not see another New Year’s Day unless you get help,’ ” Sacks recalled in the documentary.

Six months later, Sacks began seeing migraine patients at a clinic in New York City. During what would turn out to be his last amphetamine high, Sacks read a 500-page book on the theory behind migraines, with detailed case studies, written by physician Edward Liveing in the 1870s. “I read through the whole book in a state of ecstasy,” Sacks said. “With the amphetamines in me, sometimes it seemed to me that the neurological heavens opened and that the migraine was shining like a constellation in the sky.”

After that vision, Sacks began writing detailed accounts of his patients’ experiences, a process that merged his intellectual and creative passions. Embarking on this psychologically rich literary journey would sustain Sacks throughout his life.

Beyond the dichotomy

In fall 2015, Westgate was a graduate student in Oishi’s lab. With lab members squeezed into his tiny office for a meeting, Westgate recalls, Oishi walked in and asked: “Is happiness and meaning all there is?”

That meeting and the ensuing discussion marked a turning point for Oishi. He had, like most well-being researchers, been publishing papers that worked within the happiness-meaning dichotomy. Yet he had grown disillusioned by those paths’ shortcomings. For instance, why, as research has consistently shown, did happiness hinge on having considerably more money than is strictly necessary? And why did homogenous friend circles give people more happiness and satisfaction in their lives than diverse circles?

After that meeting, Westgate recalls, the team homed in on one question: If you lack money and stability, can you still have a good life?

The team looked for a third path, one filled with rich, aesthetic experiences. First the group developed a scale to measure psychological richness. The scale mirrored those used to measure happiness and meaning. Respondents rank 17 statements from 1 for strongly disagree to 7 for strongly agree. Statements include: “On my deathbed, I am likely to say ‘I had an interesting life’ ” and “My life would make a good novel or movie.” The results, appearing June 2019 in the Journal of Research in Personality, showed that scoring high in a personality trait known as “openness to experience” predicted high richness scores but not necessarily happiness or meaning.

Later research revealed that people high in richness are also emotionally intense, prone to experiencing strong positive and negative emotions. People high in meaning and happiness, meanwhile, experience positive emotions more strongly than negative emotions.

To see how the three paths — happiness, meaning and richness — play out across life, the team evaluated obituaries appearing in the summer of 2016 in the New York Times, the Singapore-based Strait Times and a local Charlottesville newspaper. Research assistants were tasked with describing obituaries using just 12 adjectives, such as “secure” and “comfortable” for happiness, “fulfilling” and “sense of purpose” for meaning and “dramatic” and “eventful” for psychological richness. Obituaries that scored high in psychological richness also scored high in meaning, but not happiness.

The research, appearing online August 12 in Psychological Review, found that major life events, such as divorce, career changes and personal tragedies, linked to higher richness, but not meaning or happiness.

Still, Oishi and his team needed to answer the obvious: Could such an intense, unpredictable and frequently unhappy life really be a path people desired? The researchers asked more than 3,100 people across nine countries — the United States, Japan, South Korea, India, Singapore, Norway, Portugal, Germany and Angola — to score 15 terms similar to those used in the obituary studies on how closely the terms described their ideal lives on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). A nine-term subset of the 15 terms showed that for most countries, people’s ideal life was most characterized by happiness and least characterized by richness, the researchers reported June 2020 in Affective Science. Nonetheless, average richness ratings ranged from 3.7 to 5.62, suggesting that people desired some richness in their lives.

Given that ambiguity, the researchers then forced participants to choose which life they desired most: happy, meaningful or rich. Fifty to 70 percent of respondents chose terms reflecting happiness and 14 to 36 percent chose meaning as their ideal life. Percentages varied by country, but a sizable minority — 7 to 17 percent — chose a psychologically rich life.

When the researchers asked 1,611 people in the United States and 680 people in South Korea if their lives would have been happier, more meaningful or psychologically richer if they could undo their greatest regret in life, roughly 28 percent of Americans and 35 percent of South Koreans reported that their lives would have been psychologically richer with a do-over.

“That suggests to me that maybe implicit in a lot of people’s desires is psychological richness: ‘I wish I had taken on that opportunity,’ ” Oishi says.

Puzzle assembly not necessary

Not everyone, however, accepts the shift from a good life dichotomy to a good life triad. “There’s a bundle of conversations to be had about these conceptually tethered concepts,” says developmental psychologist Anthony Burrow of Cornell University. “Because for some people, isn’t it possible that a psychologically rich life is a life of purpose, is a life of meaning?”

The critique is valid. As the obituary studies showed, richness and its link to major, often negative, life events appears distinct from happiness. But those negative life experiences can foster meaning. A large body of literature shows, for instance, that natural disasters and other traumatic events can trigger a phenomenon known as post-traumatic growth: a transformation that gives people a newfound appreciation for life and a desire to help others (SN Online: 4/3/19).

An experiment from several years ago illustrates how this transformation plays out. Before richness was in consideration, behavioral economist Kathleen Vohs of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis sought to understand meaning and happiness in isolation, which was tricky because happy people also tend to lead lives high in meaning and vice versa. The researchers identified only those variables linked to happiness, such as satisfying one’s needs and wants, or only meaning, such as spending time with one’s children. Their findings, appearing in 2013 in the Journal of Positive Psychology, revealed that happiness in isolation is linked to a focus on the present while meaning in isolation connects the past, present and future, often through self-reflection.

The distinction between meaning and richness, as such, hinges on whether stitching together the strands of one’s life, or coherence, is essential to building a good life. People who study meaning say yes; Oishi says no, turning to fiction to make his point. In Muriel Barbery’s 2006 novel The Elegance of the Hedgehog and Rabih Alameddine’s 2014 An Unnecessary Woman, the main characters are poor and lonely women who are neither interested in making the world a better place nor feel that their experiences add up to some greater whole. Instead, the two women, Renée and Aaliya, pursue lives filled with consuming literature, art and music, Oishi says.

“Both women appreciate moments of ineffable beauty, Proustian moments of elongated time and aesthetics, and lead a life full of inner richness,” he and colleagues wrote in 2019.

Oishi’s proposition is simple, yet radical: Experiences, whether mostly vicarious as with Renée and Aaliya, or firsthand, can offer a good life without summing up to anything greater than their parts.

“Ideally, we want to have all three: happiness, meaning and psychological richness,” Oishi told me in an e-mail. “But having just one is sufficient to lead a good life.”

The creative impulse

After the neurological heavens opened, Sacks published his own book on migraines in 1970. He followed it with Awakenings in 1973, documenting the miraculous recovery and relapse of catatonic patients who began to clap, walk and talk after treatment with a medication for Parkinson’s disease, before fading back into unresponsiveness.

Despite his lifelong intellectual and creative frenzy, Sacks remained ever alone. After a brief fling at age 40, he was celibate for the next 35 years.

“He was not happy. He was creative. He was productive. And he was moving forward,” Burns says. “And I think if one is creative, productive and moving forward, one is moving toward happiness.”

Though Burns uses the term “creative” casually, the pursuit of art seems uniquely suited to those seeking, or forced into, a rich life. “People who score high in openness to experience tend to lead more creative lives,” says Oshin Vartanian, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Toronto.

And Oishi’s work has shown that aesthetic experiences increase richness. For instance, in a 2020 study in the European Journal of Personality, Oishi and colleagues compared richness levels between students studying abroad and students who remained on campus. Though both groups started at the same richness levels, richness scores among the students studying abroad went up after 12 weeks.

Student diaries revealed that the study abroad students participated in considerably more artistic activities, such as going to museums and concerts, than students who remained on campus. Engagement with art, Oishi says, “explained partially why the study abroad group had higher psychological richness.”

As COVID-19 variants ricochet around the globe, a great many people are now like those students studying abroad — not traveling, but dosed in a different kind of richness. Here, in this foreign terrain, we too seek beauty.

Scientists have largely focused on the artistic genius, the prototypic creative, Vartanian says. But the pandemic suggests that we should also study, and encourage, the everyday creative.

Vartanian counts himself among this everyday lot. During the pandemic shutdown, someone gave him a broken play structure for his children. Vartanian couldn’t access the parts he needed to fix it, so he learned how to chisel and do woodwork to get the apparatus in working order. “Doing things I’d never done before,” Vartanian says, “was so greatly satisfying for me.”

I recognize the feeling. When I entered the pottery studio, I knew nothing of the craft. Simply centering the clay on the wheel took me seven lessons. While I can now center small lumps of clay with relative ease, beautiful forms elude me. A half year on, I have thrown misshapen bowls, a smattering of wobbly cups and precarious vases that fold at the neck. I am, at my own life’s midpoint, awash in imperfect vessels.

Completing the triad

In the Venn diagram of the good life, Sacks spent much of his time outside all three circles. By midlife, though, psychological richness had become his beacon.

Yet, in crafting his patients’ stories, Sacks made his life about something larger than himself, Burns says. “He turned the mirror around [and said,] ‘I’m going to look outward in order to also look inward.’ ” Sacks had landed at the overlap between richness and meaning.

Then, in his late 70s, Sacks fell deeply, madly in love. After a lifetime of struggle, he finally felt he belonged, not just in literary or academic circles but within himself. In that adieu, Sacks remarked: “My predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written.”

Gratitude, research shows, is the language of happiness. At the sunset of his life, then, Sacks had arrived at the junction of those three paths.

He nailed the ending, Burns says. “That’s given to very, very few of us.”