Implicit prejudice

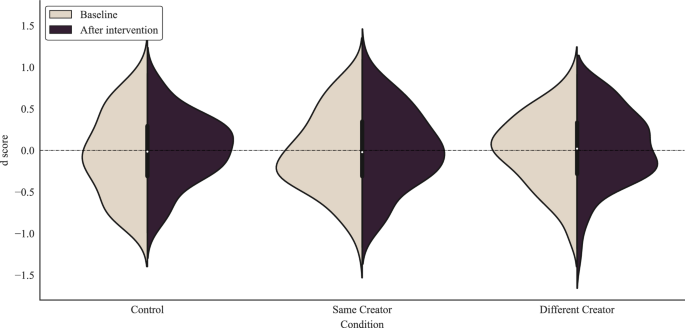

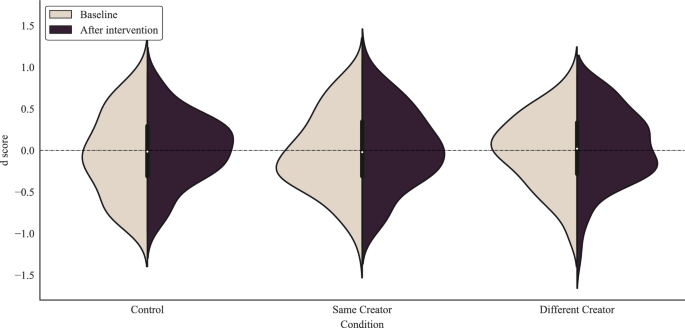

We had postulated that implicit prejudice would decrease for participants in the same- and different-creator conditions, but remain approximately constant for those in the control condition (Hypothesis 1). To test for changes in implicit prejudice following the disclosure videos, d scores were created from each participant IAT responses both pre- and post-intervention. The distributions of d scores are shown in Fig. 3 for each condition. Due to the non-Gaussian distribution of the data, we used a non-parametric paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test to test for differences in the implicit prejudice d scores from before and after the disclosure stimuli within each condition. Against our prediction, no significant differences were found between pre- and post-disclosure d scores for any of the three conditions. Average values and p values are reported in Table 2.

Explicit prejudice

To test for differences in explicit prejudice, analyses of variance (ANOVA) with planned contrasts were used for the explicit prejudice measures.

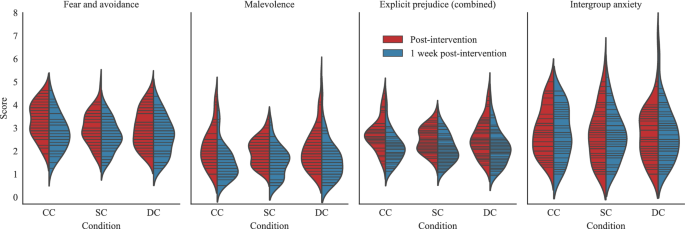

Using the combined explicit prejudice measure, a significant effect was found when comparing between conditions (\(F(2, 317) = 3.093\), \(p = .047\)). Planned contrasts showed that participants in the same-creator condition had significantly lower explicit prejudice after watching the disclosing stimuli than those in the control condition (\(M_{SC} = 2.53\); \(M_{CC}=2.76\); \(t(317) = -2.362\), \(p = .019\)). The different-creator condition also had significantly lower explicit prejudice than the control condition (\(M_{DC} = 2.57\); \(t(317) = -1.990\), \(p = .047\)), as stated in Hypothesis 2. However, against our prediction, the scores for the same- and different-creator conditions did not significantly differ from each other (\(t(317) = -.432\), \(p = .666\)). The distributions of scores for the explicit prejudice scales are labelled as “Post-intervention” in Fig. 4.

The same pattern between conditions was found within the fear and avoidance sub-scale (\(F(2, 317) = 5.689\), \(p = .004\)), where participants in the same-creator condition had significantly lower fear and avoidance scores after watching the disclosing stimuli (\(M_{SC}=2.99\)) than those in the control condition (\(M_{CC} = 3.34\); \(t(317) = -3.196\), \(p = .002\)). Participants in the different-creator condition also had significantly lower scores than those in the control condition (\(M_{DC} = 3.05\); \(t(317) = -2.714\), \(p = .007\)), but the same- and different-creator conditions did not significantly differ from each other (\(t(317) = -.562\), \(p = .575\)).

Finally, no significant differences between conditions were found within the sub-scale of malevolence or any of its planned contrasts (\(F(2, 317) = .460\), \(p = .632\)), although the malevolence values were already low (an average score of 2.17 out of 7 in the control condition, vs. the average value of 3.34 out of 7 for the fear and avoidance subscale), so changes here would not necessarily provide substantial prosocial value.

Intergroup anxiety

A planned contrast ANOVA was used to compare intergroup anxiety between conditions (\(F(2, 317) = 2.27\), \(p = .105\)). Those in the same-creator condition had significantly lower intergroup anxiety (\(M_{SC}=2.66\)) than participants assigned to the control condition (\(M_{CC}=2.99\); \(t(317) = -2.075\), \(p = .039\)). As in explicit prejudice, participants in the same- and different-creator (\(M_{DC} = 2.73\)) conditions did not significantly differ from each other (\(t(317) = -.555\), \(p = .579\)), nor did the scores from participants from the different creator condition with respect to the control condition (\(t(317)=-1.585\), \(p=.114\)). The distributions of scores for the three conditions are shown in Fig. 4.

Behavioural measures

Finally, a planned contrast ANOVA was used to assess the behavioural items in our survey. Nor the behavioural items for volunteering (\(F(2, 317) = .997\), \(p = .370\)) or receiving information, (\(F(2, 317) = .364\), \(p = .695\)) differed significantly across the 3 conditions (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics).

Interim discussion

To summarise prejudice results, no significant differences were found in implicit prejudice or in the two behavioural measures directly after watching the disclosing video. However, measures of explicit prejudice, and specifically intergroup anxiety and the subscale of fear and avoidance, showed that those exposed to the disclosure video (both in the same- and the different-creator conditions) had lower prejudice and intergroup anxiety levels than those who were not. While these explicit prejudice results support our initial hypotheses, prejudice levels between the same- and different-creator conditions did not differ from each other. Further exploration of parasocial relationship strength between these conditions was therefore conducted.

Influence of parasocial relationship strength on prejudice

We had predicted (Hypothesis 3) that parasocial relationship strength towards Creator A (i.e., the disclosing target) after the intervention (i.e., PSR 2) would be greater for participants assigned to the same-creator condition than those in the different-creator condition. Before testing this hypothesis, we ran a control check to ensure that the individual differences between the two creators did not influence PSR strength. A Kruskal-Wallis test compared PSR 1 strength across the three conditions after watching the relationship-building stimuli. No significant differences were found between participants from the same-creator condition, the control condition (both of whom watched the Parasocial Fast Friends Paradigm video featuring Creator A), and the different-creator condition (who watched the PFFP video featuring Creator B; \(H=.134\), \(p=.935\)).

Contrary to Hypothesis 3, participants that watched Creator A’s relationship-building stimuli in the same-creator condition did not produce significantly greater PSR2 strength towards them after the disclosure about mental health, when compared to the different-creator condition (which watched the relationship-building video from Creator B and then the disclosure video from Creator A (Mann-Whitney \(U=6591, p=0.32\)).

Even though our experimental protocol failed at manipulating PSR 2 strength across conditions, we found a significant correlation between PSR 2 strength and the combined explicit prejudice measure that corroborated our Hypothesis 4, which stated that greater PSR to the disclosing creator would result in lower prejudice levels after disclosure (Pearson’s \(\rho = -.296\), \(p < .001\)). PSR 2 also correlated significantly with the explicit sub-scales of fear and avoidance (Pearson’s \(\rho = -.274\), \(p < .001\)) and malevolence (\(\rho = -.241\), \(p < .001\)).

We were also interested in understanding whether the disclosure of BPD would strengthen or weaken the parasocial relationship created between participants in the same-creator condition and Creator A. A paired Wilcoxon test comparing PSR 1 and PSR 2 values for this group found that PSR strength increased after the disclosure video (\(W=1695\), \(p<.001\)).

Finally, a means comparison was run to compare whether the relationship-building stimuli alone (where either creator spoke about themselves broadly using the Parasocial Fast Friends paradigm) or disclosing stimuli alone (where Creator A spoke about her BPD experiences) were more effective at creating PSR strength. A Mann–Whitney U test revealed that PSR 2 from the different-creator condition (following the disclosure stimuli alone, \(M_{DC} = 3.91\)) was significantly higher than PSR 1 from the same-creator and control conditions (following the relationship-building stimuli alone, \(M_{SC,CC} = 3.68\); \(U=10398, p=.023\)).

To summarise PSR analyses, priming participants with the relationship-building stimuli before disclosure did not result in greater PSR strength than the disclosure stimuli alone, so the condition manipulation within the present study did not produce the expected results. If PSR strength mediates prejudice reduction, this manipulation failure is a possible explanation for why no significant differences were found between the same- and different-creator groups for explicit measures of prejudice or intergroup anxiety. In spite of this, PSR strength across conditions was significantly correlated with explicit prejudice, confirming our Hypothesis 4. Moreover, disclosure of BPD increased the strength of the PSR towards the disclosing creator for participants in the same-creator group. Lastly, the disclosure video on its own resulted in greater PSR strength than when either creator spoke broadly about themselves using the PFFP.

Causal analysis

Alongside pre-registered analyses, we performed a causal inference analysis to confirm that the significant changes found in explicit measures of prejudice were a result of experimental manipulation, and not extraneous confounding variables. The analysis was performed using DoWhy33.

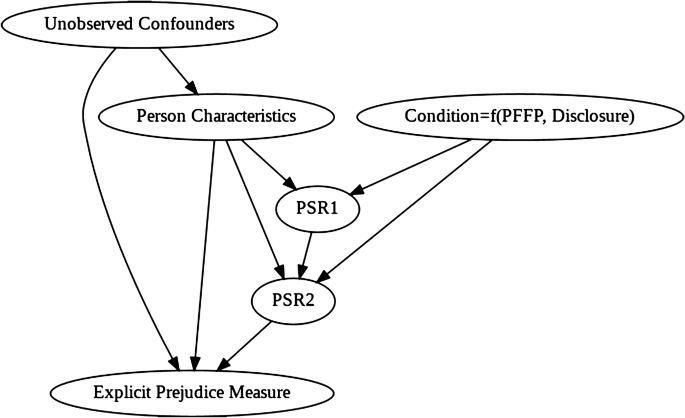

We first constructed a causal graphical model based on our assumptions about the mechanisms for prejudice change in our experiment. This model is shown in Fig. 5. Namely, PSR 1 and PSR 2 are affected by each individual’s characteristics, as well as the experimental group to which they were assigned (“Condition”). The effect of the intervention on explicit prejudice is mediated by parasocial relationship strength (as well as the individual’s characteristics). “Condition” is the product of the identity of the creator in the PFFP and whether or not the participant watched the disclosure video. Note that, for participants in the control condition, PSR 2 is the same as PSR 1.

Five targeted confounders were considered: age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and proximity to loved ones with mental illness (summarised as “Person characteristics” in Fig. 5). Unobserved confounders were also considered for unrecorded individual differences. The treatment variable (“Condition” in Fig. 5) was used to compare the three groups separately for each explicit prejudice measure.

To estimate causal effects, we calculated the Average Treatment Effect (ATE), which measures the expected change to an outcome variable based on the group/condition. ATE estimates were generated using inverse propensity score weighting to account for possible imbalances in the confounders across the three experimental groups. The value of the ATE represents the average expected change in explicit prejudice (with respect to the baseline group) as a result of the intervention. We performed pairwise comparisons between the three groups. Our results are summarised in Table 3.

Finally, in cases where a causal effect was found, we used three refutation methods to asses its robustness. The first refutation method added a random common cause to the dataset. In the second method, a data subset refuter bootstraps the dataset to replicate the analyses using different subsets of data. The third refutation method consists of repeating the analysis after randomly permutating the variable that indicates to which group an individual belongs, and is equivalent to having a placebo treatment. For the first two methods, the estimated ATE is not expected to change if the causal effects are robust. For the placebo method, the ATE is expected to be close to zero.

Overall, the results in Table 3 are consistent with those from our previous sections. Robust causal effects were found for the fear and avoidance subscale for the different- and same-creator groups with respect to the control group, showing that the disclosure video had a significant effect on the prejudice levels. Significant causal effects were also found for the combined explicit prejudice scale, but, as expected, not for the malevolence subscale.

When estimating causal effects for the intergroup anxiety measure across groups, we found that the reduction in prejudice found in the different creator condition was not significant with respect to the control group. However, the effect was robust for participants in the same creator group (vs. the control group).

As in previous analyses, no causal effects were found between belonging to the same vs. different-creator conditions. Considering that our manipulation failed to create higher PSR2 values for participants in the same-creator group than for those in the different-creator group, the lack of significant causal effects here is not surprising.

Long-term prejudice reduction

Our final hypothesis (Hypothesis 5) stated that after one week, participants from the same- and different-creator conditions would still show lower prejudice levels (measured by the explicit prejudice and behavioural scales) than participants in the control condition. Summary statistics for explicit and behavioural prejudice measures directly after the intervention and for the 1-week follow-up survey are reported in Table 4. Power analyses carried out on GPower34, indicated that a minimum of 246 participants across the three groups were required to conduct a mean comparison across the conditions to detect a small effect size. Whilst the longitudinal sample did not meet this requirement (only 147 participants completed the follow-up survey; \(n_{SC} = 49\), \(n_{DC}=58\), \(n_{CC}=40\)), power analyses were satisfied for conducting Wilcoxon paired tests within conditions, comparing prejudice levels directly after watching the stimuli, and one week later. We did not find significant differences between post-intervention and 1-week follow-up surveys (after Bonferroni correction) for the combined explicit prejudice measure (corrected \(p_{CC}=0.8\), \(p_{SC}=1\), \(p_{DC}=1\)), nor for the the fear and avoidance subscale (corrected \(p_{CC}=0.26\), \(p_{SC}=1\), \(p_{DC}=1\)), the malevolence subscale (corrected \(p_{CC}=0.3\), \(p_{SC}=1\), \(p_{DC}=1\)), or intergroup anxiety (corrected \(p_{CC}=1\), \(p_{SC}=1\), \(p_{DC}=1\)).

As for the behavioural items in the 1- week follow-up survey, participants were asked if they had thought about people with mental health issues such as BPD in the past week. While we recognise sample size requirements were not met for analysis of variance, an exploratory ANOVA found that those in the same-creator condition had thought about people with BPD more than those in the different-creator condition, which in turn had more thoughts than the control condition. Whilst none of these planned contrasts were significant (\(F(2, 142) = 1.716\), \(p=.183\)), the comparison between the same-creator and control conditions was close to significance (\(t(142) = 1.833\), \(p = .069\)), and may reach significance with an adequate sample size.

Similarly, when asking participants if in the last week they had thought specifically about helping those with mental health issues such as BPD, an exploratory ANOVA did not reach significance (\(F(2, 143) = 2.096\), \(p=.127\)). Those in the same-creator condition had thought about taking prosocial action significantly more than those in the different-creator and control conditions combined (\(t(143) = 2.038\), \(p = .043\)), although again this is only a suggestive finding due to the small sample size.

One final behaviour measure was coded, where participants were asked whether they had actively contributed towards (e.g., by having positive and educational conversations or donating time or money towards mental health initiatives), or against (e.g., by having negative conversations about mental health or donating time or money to initiatives that disregard mental health) people with mental health issues. None of the participants that filled the follow-up survey reported actively acting against people with mental health issues. 15 participants (10.2%) contributed towards people with mental health issues (7 from the same-creator condition, 5 from the different-creator condition, and 3 from the control condition). Actions reported by participants in support of mental health issues included having educational conversations about mental health with loved ones, further educating themselves through enrolling in courses, signing petitions, and donating and hosting fundraisers for mental health charities.