Whereas the first definition for “queer,” according to Oxford and Dictionary.com, is “strange, odd.” Another definition refers not only to gay people but also to “a person whose sexual orientation or gender identity falls outside the heterosexual mainstream or the gender binary,” according to Dictionary.com. That could mean “transgender,” “gender neutral,” “nonbinary,” “agender,” “pangender,” “genderqueer,” “demisexual,” “asexual,” “two spirit,” “third gender” or all, none or some combination of the above. Being queer is, as bell hooks once said, not “about who you’re having sex with — that can be a dimension of it — but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and it has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

While we’re here, the Q in “L.G.B.T.Q.” currently can stand for both “queer” and “questioning.”

Confused? You should be! “Queer” can mean almost anything, and that’s the point. Queer theory is about deliberately breaking down normative categories around gender and sex, particularly binary ones like men and women, straight and gay. Saying you’re queer could mean you’re gay; it could mean you’re straight; it could mean you’re undecided about your gender or that you prefer not to say. Saying you’re queer could mean as little as having kissed another girl your sophomore year at college. It could mean you valiantly plowed through the prose of Judith Butler in a course on queerness in the Elizabethan theater.

Given the broad spectrum of possibility, it’s no surprise that many people — gay or straight — have no idea what it means when someone self-identifies as queer.

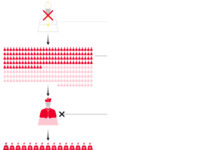

But this is important: Not all gay people see themselves as queer. Many lesbian and gay people define themselves in terms of sexual orientation, not gender. There are gay men, for example, who grew up desperately needing reassurance that they were just as much a boy as any hypermanly heterosexual. They had to push back hard against those who tried to tell them their sexual orientation called their masculinity into question.

“Queer” carries other connotations, not all of them welcome — or welcoming. Whereas homosexuality is a sexual orientation one cannot choose, queerness is something one can, according to James Kirchick, the author of “Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington.” Queerness, he argues, is a fashion and a political statement that not all gay people subscribe to. “Queerness is also self-consciously and purposefully marginal,” he told me. “Whereas the arc of the gay rights movement, and the individual lives of most gay people, has been a struggle against marginality. We want to be welcomed. We want to have equal rights. We want a place in our institutions.”

Many gay people simply prefer the word “gay.” “Gay” has long been a generally positive term. The second definition for “gay” in most dictionaries is something along the lines of “happy,” “lighthearted” and “carefree.” Whereas “queer” has been, first and foremost, a pejorative. For a certain generation, “queer” is still what William F. Buckley, jaw clenching, called Gore Vidal on ABC in 1968 — “Listen, you queer” — before threatening to “sock you in your goddamn face.”

What I hear most often from gay and lesbian friends regarding the word “queer” is something along the lines of what Sedaris pointed out: “Nobody consulted me!” This wasn’t their choice.