Republicans in the Ohio House are trying, again, to limit the health care transgender children can access regardless of parental consent.

House Bill 454 would outlaw the use of puberty blockers, hormones and gender reassignment surgery for children under the age of 18. If approved, doctors who broke the law could face professional discipline and civil lawsuits. Teachers would also be required to tell parents about a “minor’s perception that his or her gender is inconsistent with his or her sex.”

Twenty-five of Ohio’s 64 House Republicans signed up to sponsor the bill, which is nicknamed the Save Adolescents from Experimentation or SAFE Act.

Supporters say the law would protect parents and children from being “bullied” into treatments that can be irreversible. Opponents say banning treatment for one specific group is unconstitutional, grossly disrespectful and a serious threat to the health of Ohio’s most vulnerable children.

Treatment in Ohio

Only a handful of medical providers in the Buckeye State provide gender-affirming medical care to minors, such as puberty blockers, hormones and surgery.

Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio doesn’t prescribe hormones to anyone under 18.

Most family doctors won’t either, said Liam Gallagher, the program director for an LGBTQ youth nonprofit called Kaleidoscope Youth Center. Transgender kids who want to transition get referred to specialized programs at a handful of major hospitals.

One of those is the THRIVE program at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus where Dr. Scott Leibowitz serves as medical director.

“We work with parents and families on all ends of the belief spectrum …,” Leibowitz said. “Ethical and morally responsible care respects families of different cultures, different races and different religious viewpoints.”

He rejected the idea that anyone at THRIVE would pressure parents into medicating their children.

“Any type of treatment decision that would have potentially irreversible effects, that is something that is not ever rushed,” Leibowitz said.

That can mean waiting on hormones until the child’s 18th birthday.

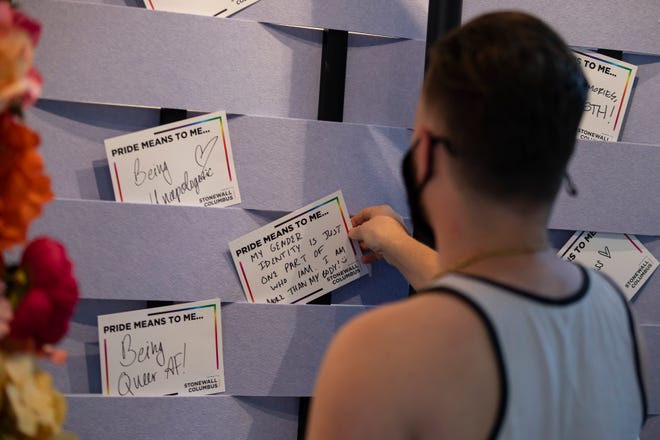

Gallagher, who began his own transition at 21, said he’s observed that most Ohio doctors want both parents to agree before they prescribe medication. Group sessions at the youth center where he works can feel like “an echo chamber where we talk about the frustration of having to wait.”

“The waiting felt like years for me even though it was just months,” Gallagher said.

For a lot of the teenagers who frequent Kaleidoscope, gender-affirming care doesn’t go beyond choosing clothing, haircuts and pronouns that fit them.

When it comes to surgery – something HB 454 calls gravely concerning – Liebowitz was more circumspect, saying it depended on the “emotional maturity of a young person.”

Data on how many minors undergo this kind of surgery is scarce, but the standards of care written by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommend frank discussions about the lifelong impacts on fertility.

The standards state that for most minors “genital surgery should not be carried out until patients reach the legal age of majority to give consent for medical procedures in a given country.”

The larger issue for Leibowitz is that the fear of surgery is being used as a cudgel to beat back against all forms of medical intervention.

“It’s about raising fear for unknowing people who think the medical community is out to harm patients,” Leibowitz said.

‘I’m not a bad parent’

That’s how James Lewis, a Columbus-area parent, felt when his then-12-year-old daughter started questioning her sexuality and gender identity.

“She explored having girlfriends and boyfriends,” Lewis said. “It wasn’t a moral issue for us.”

Then, she asked to cut her hair and wear more masculine clothing. That wasn’t a problem either until she refused to wear shorts to soccer practice and Lewis discovered his daughter had been cutting herself. Diagnoses of depression, anxiety and gender dysphoria soon followed.

She started asking about transition, but Lewis wasn’t comfortable with the idea when she had so many other mental health diagnoses.

“I don’t think we should allow children to make adult choices,” Lewis said.

His daughter eventually concluded that her feelings better aligned with body dysmorphia, a preoccupation with perceived defects or flaws in appearance, and she’s since recovered. She’s in college, and Lewis is optimistic about her future.

The USA TODAY Network Ohio Bureau spoke with Lewis’ daughter, and she confirmed this story. She is not being named due to a request for privacy.

Lewis said the biggest issue he had with the medical community during those years was the way he they pushed hormones and other gender-affirming therapies.

He was warned that his decisions might cause her to take her own life.

About 85% of transgender adolescents reported “seriously considering suicide,” according to a 2019 study published in the American Academy of Pediatrics. Family acceptance can reduce those risks.

But it felt to Lewis like the practitioners he spoke with couldn’t or wouldn’t accept that some children might be confused or claim to be something they’re not.

“I think the human experience, as much as we want to make it simple, I think that’s doing injustice to everyone,” Lewis said. “With this bill, I think the intent is to prevent being too hasty.”

Opponents of HB 454 strongly disagree.

“Banning ethically appropriate and life-saving treatment options universally for all youth, on the grounds that they are not indicated for some youth, takes shared decision-making away from the family and doctor and places it entirely into the hands of Ohio politicians,” Leibowitz said.

The science and the studies

At the heart of the debate over HB 454 is this question about whether children like Lewis’ daughter are the exception or the rule.

Supporters of the bill claim that almost all children who experience gender dysphoria will “desist” or grow out of it by adulthood.

“The standard of care for gender dysphoria should be watchful waiting, which doesn’t mean we do nothing,” said Dr. Andre Van Mol, a family physician who works with a conservative advocacy group called the American College of Pediatricians. “We protect gender dysphoric children from making permanent, life-altering mistakes.”

These studies, including those referenced in the Ohio bill, are considered problematic because they often don’t distinguish between children who are transgender and those who are non-conforming. The latter refers to children who don’t fit the stereotypes associated with their gender.

“Those young children were never declaring they were transgender in the first place,” Leibowitz said. “They were gender diverse.”

A 2013 study from the University Medical Center in Amsterdam followed 127 adolescents who had been referred to a clinic for gender dysphoria. Researchers claimed 63% grew out of their dysphoria by adulthood, but 38 of the kids were considered “sub-threshold” for a diagnosis in the first place.

Major medical groups like the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics strongly support medically necessary transition-related care for minor patients.

Supporters said it’s better to look at long-term studies like the one psychologist Kristina Olson is running out of the University of Washington. Her research aims to develop criteria for determining which gender-diverse children go on to transition.

“Our study suggests that it’s not random,” Olson told The Atlantic in 2019. “We can’t say this kid will be trans and this one won’t be, but it’s not that we have no idea.”

‘I didn’t change overnight’

Another theory written into HB 454 is that the onset of gender dysphoria can be rapid or sudden and therefore potentially the result of outside influences like peer groups and social media. That’s what Lewis believes happened to his daughter.

But Gallagher, of Kaleidoscope Youth Center, says that’s not true. When he came out to his parents at 21, it might have looked sudden, but he’d been thinking about it for years and preparing to start testosterone for months.

“For the person we are coming out to, they are seeing the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

TransOhio Chair James Knapp started his transition at a time when doctors required people to live openly as the opposite gender for at least one year before getting hormones.

“Trans kids who are trying to access gender-affirming care have to jump through so many hoops,” Knapp said. “You have to have two physicians sign off before you can start talking about hormone blockers.”

The hurdles aren’t all medical, either.

“Look,” Gallagher said, “As much as I love my identity, and I love my experience, I am going to be honest: No one wants to be trans. It is really difficult.”

Trans people – especially transgender women of color – face higher rates of unemployment, homelessness and violent crime.

“It wasn’t like I read a book that talked about being a magician and suddenly I was a magician,” Gallagher said. “This is something I have always felt.”

The odds in Ohio

If passed, Ohio would be the second state to ban medical interventions for transgender youth. At least 15 states introduced similar legislation, but only Arkansas passed a law. A federal judge blocked its implementation soon after.

Ohio lawmakers introduced a similar bill last General Assembly but it didn’t get a hearing.

Still, opponents of the proposal concede that Ohio’s legislature seems to grow a little more conservative each year. In addition to HB 454, Republicans introduced a bill to ban transgender girls from participating in women’s sports, and they inserted language into the state budget that lets doctors refuse care on religious grounds.

“We had the gay panic of the 1950s through the 1980s. Now it’s the trans panic,” Gallagher said. “It has just shifted. Instead of being worried about ‘the homosexual’ in the classroom, we’re afraid of the scary trans person in the bathroom.”

Anna Staver is a reporter for the USA TODAY Network Ohio Bureau, which serves the Columbus Dispatch, Cincinnati Enquirer, Akron Beacon Journal and 18 other affiliated news organizations across Ohio.