NYC Pride, the same organization that runs New York’s annual Pride Parade, has a new brand that you could say is 53 years in the making.

On the night of June 28, 1969, NYC police raided the Stonewall Inn, one of the most popular bars in New York. But this night, the clientele, who usually acquiesced to the constant police harassment, fought back. Five days of protests in the area followed as the beginnings of the gay rights movement was ignited. A year later, on the anniversary of the riots, thousands of people marched in the streets of New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and a few other large cities in what would become the first Pride parades in the country. And by 1978, artist and gay-rights activist Gilbert Baker created the powerful icon that became synonymous with the Pride movement: a rainbow flag.

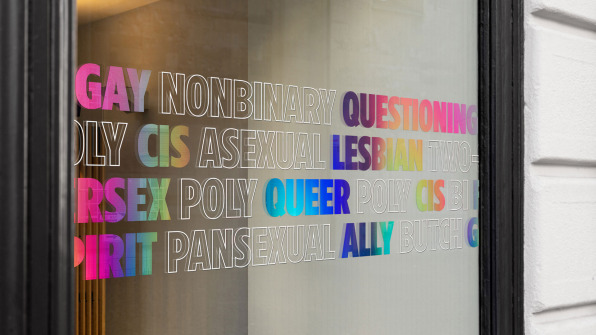

Capping the story there makes for a tidy ending to the Pride brand. But Pride continued to grow. People created new flags to depict Pride, specifically for people who are transgender, nonbinary, and pansexual. In the late ’80s, many activists pushed for the movement’s expansion, creating the LGBT acronym—an acronym that has swelled over the decades to LGBTQIA+ (the meaning of which can differ depending who you’re talking to).

“Some people call it the alphabet, but I think it’s much more than that,” says Dan Dimant, media director for NYC Pride. “And I think the challenge for us is to understand that there are many, many more communities than we could ever fit into the LGBTQIA+ alphabet. Short of adding and adding and adding to one long list of letters, what we believe is that it’s really important to really embrace each of those individual communities and what is most meaningful for them.”

And so, with an ambitious new brand, NYC Pride wants to unify the Pride movement while celebrating the individuality of its ever-growing list of emerging communities. (The rebranding arrives in the wake of some controversy regarding NYC Pride’s handling of the annual Parade and its inclusion of police and major sponsors—which has led the Reclaim Pride Coalition to offer a Pride Parade alternative called the Queer Liberation March.)

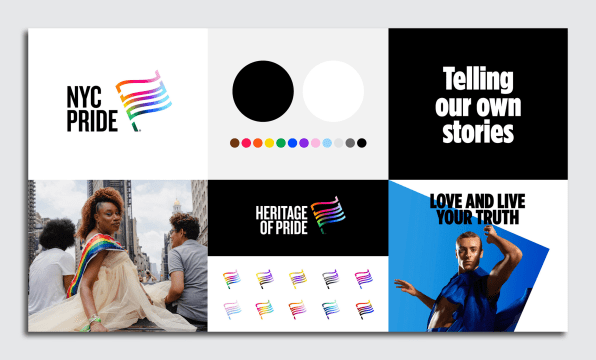

The core of the updated brand is a new logo—created as a pro bono project by the creative consultancy Lippincott (a firm that is perhaps best known for creating the modern Starbucks siren). At first glance, the new logo is a gradient rainbow flag made up of the letters NYC. But the rainbow is just the beginning. Because when you see it animated, that gradient breaks its rainbow, shimmering to reveal all of the other pride flags. Today, those additional flags include intersex, asexual, trans, pansexual, bisexual, lesbian, nonbinary, gay, and polyamorous. But there’s no limit to what other flags can be appended next.

“The idea is that this kind of diversity is additive,” says Dimant. So in 5 or 10 years or 20 years, NYC Pride can include people who aren’t being acknowledged today—and the logo will only be more colorful as a result. Dimant also notes that mixing all these gradients side-by-side celebrates the natural intersectionality of genders and sexualities in ways that modern, single-serve flags don’t. “You can identify as a woman, and you can identify as queer, and those things aren’t mutually exclusive—and that’s just one example.”

Given the complexity of this approach, you might ask, why not just re-embrace the rainbow flag as the core of Pride, with its array of colors depicting inclusion of anyone who’d like to take part? Wouldn’t that be simpler? Maybe, but the approach wouldn’t work. For one, the colors in the rainbow flag actually have specific meanings (including sex, life, and nature). They aren’t simply symbols for people of different backgrounds coming together under one cause.

Secondly, NYC Pride doesn’t see its role as prescribing a brand onto a community. As Dimant explains, Pride has been a grassroots movement since the Stonewall Uprising, and, to this day, even as Pride has become a global movement, different nonprofits run their Pride events, city to city, using a staff of mostly volunteers. It’s anything but your standard brand exercise, where some multinational corporation exerts standards across the world.

“It’s not . . . our place to redefine [any] flag that’s been developed by the community,” says Dimitri Theodoropoulos, senior design director at Lippincott. “We’re really driven by the community and that creation—and not trying to come up with a new meaning for it, but putting a different spin on it.”

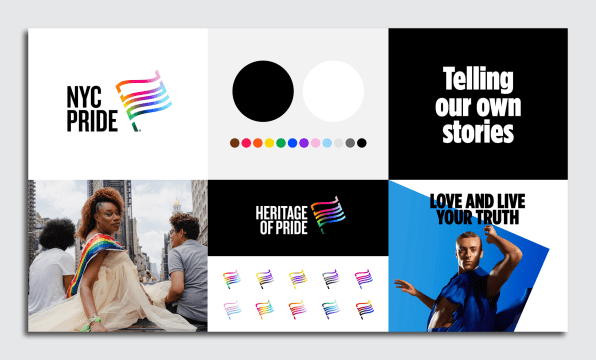

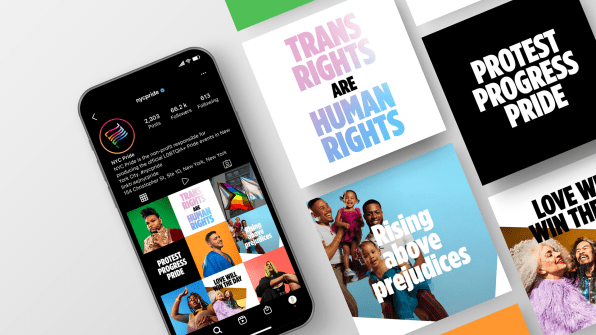

Beyond adding representation to the NYC Pride logo, Lippincott also built out a larger brand system for NYC Pride to use. Even though the organization runs marquee events like the NYC Pride Parade, it wants a system that works for day-to-day activism and protest.

For this task, Lippincott sourced the typefaces Knockout (in the logo) and Gotham (in the extended branding) by the New York-based foundry Monotype. The aforementioned inclusive “living gradient” used in the logo can be applied to this type. Meanwhile, whenever photography mixes into the brand system, it’s always placed on a diagonal—an effect that I’d argue adds an ad hoc-ness to the visual system, subliminally reminding the viewer that what they’re looking at was likely built by a volunteer. But there’s intentionally not much more to the branding standard: It’s meant to be simple enough to follow that anyone can pick it up and run with it. Because it’s made for them.

NYC Pride and Lippincott acknowledge that, as with any branding exercise, some people will be critical of the approach. Theodoropoulos says that he hopes everyone in the Pride community can see themselves in it somehow.

“The thing about Pride is, it’s really the only time as a queer person that you don’t feel like you’re the only one in the room; it’s the one day of the year where we’re the majority in this space,” says Theodoropoulos. “You learn at a young age, people dispassionately commit violence against our community. You walk around with a semblance of, ‘Watch out. Is this a safe space for me?’ The flag is always something you see. ‘This is a safe space for me. I can be myself here.’”

And now, that flag has made a new promise: to evolve, however needed, to include everyone.