Rain Weinstein had expected that students who didn’t support his school’s LGBTQ community might show up to the walkout he’d helped organize.

The demonstration at Palm Harbor University High was part of a movement across Florida, led by queer students protesting a bill they and other critics call “Don’t Say Gay.”

But Weinstein, a 17-year-old senior, didn’t think the detractors would number in the hundreds. He didn’t think he’d have to herd his group to one area so no one would get swallowed in the chaos. He didn’t think he’d get spit on or called homophobic slurs. He didn’t think a student would pull out a Trump 2020 flag alongside the gay and transgender pride flags, or that someone would yell, “Kill ‘em all” over and over.

But that day in early March, Weinstein experienced the first consequences of a bill that critics warned would lead to censorship of LGBTQ voices and embolden some to harass queer students, teachers, administrators and their allies. And while the bill targeted instruction in younger grades, it left catchall language that gay rights advocates worried would be used to control classrooms up through high school.

More than a dozen times in Florida school districts, that’s exactly what happened, according to interviews with students and several news reports from around the state.

Since the beginning of March, when the bill picked up steam in the Legislature, students who organized protests like Weinstein’s said they were silenced by administrators and bullied by their peers and online trolls. Books with LGBTQ characters and themes were removed from libraries and curriculums. Some teachers quit their jobs, and others who stayed were asked to take down flags or signs they hung up to provide a welcoming environment in their classrooms.

Lawmaker debate:Florida Legislature passes ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill, sends to Gov. DeSantis for signature

Bill becomes law:Gov. DeSantis calls out Leon County as he signs what opponents call ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill

Historical context:Historians draw parallels between ‘Don’t Say Gay’ legislation and purge of gay teachers decades ago

‘Worst it’s ever been’:Culture wars got personal this legislative session

The bill wasn’t cited as the reason for action in every case, but LGBTQ advocates say the legislation and its surrounding rhetoric has created a hostile environment ripe for these types of attacks — even before the bill becomes law on Friday, along with a slate of new laws including two more that target school curriculum.

“Words have consequences,” said Brandon Wolf, press secretary for the LGBTQ rights organization Equality Florida, “and the dehumanizing rhetoric that has been used by powerful people in this state is absolutely having a negative impact on young people.”

“It’s so much farther reaching than even the mere text of the bill,” said Maxx Fenning, 20, president and co-founder of PRISM, a South Florida nonprofit serving LGBTQ youth. Students “are terrified.”

Weinstein, who is transgender, and fellow protesters felt that fear after their walkout. A Pinellas County Schools spokeswoman said that students who had “acted inappropriately” had been disciplined but declined to elaborate. School staff planned for the event, spokeswoman Isabel Mascareñas said, and had extra student resource offices on campus “to help keep students safe.”

That was the opposite of how Weinstein felt as he headed back to class with the same students who jeered him in the courtyard.

Said Weinstein: “No one felt safe.”

‘It’s exhausting’

House Bill 1557, formally titled Parental Rights in Education, bans classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in Kindergarten through third grade. It also prohibits discussions that aren’t “age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate” in remaining grades. The state Department of Education will set those standards.

It should be up to parents to decide when or if to discuss those matters, the bill’s proponents said. Attorney General Ashley Moody’s office, who this week asked a federal judge to dismiss the lawsuit challenging the bill, called it a “modest limitation … neutrally allowing all parents, no matter their views, to introduce those sensitive topics to their children as they see fit.”

However, bill supporters have come under fire for using gay stereotypes and indoctrination in schools to defend its purpose.

In March, Gov. Ron DeSantis’ press secretary, Christina Pushaw, tweeted that those who didn’t support the bill were groomers, among the first of now many conservative politicians and pundits who have put a modern spin on a century-old attack on LGBTQ people as pedophiles. DeSantis himself has said the bill would keep younger students from learning about sex and stop indoctrination of “transgender ideology” in schools.

Democratic legislators sought to clarify the bill’s language and intent, but Republican lawmakers rejected a swath of amendments.

The bill’s Senate sponsor, Dennis Baxley, R-Ocala, said during debate that he was aiming to curb what he saw as indoctrination in schools — another false narrative used by Florida lawmakers decades ago in the 1950s to out and fire gay and lesbian teachers and college professors.

Across the state, LGBTQ students and others organized protests.

Jack Petocz, a junior at Flagler Palm Coast High, set up a statewide walkout, similar to student-led demonstrations to protest gun violence in 2018 following the slaying of 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High in Parkland.

More than 500 of his fellow students, and thousands across the state, participated with varying levels of support from other students and administrators.

Petocz, who is gay, was suspended after giving out more than 200 Pride flags at his rally. Then, he said, after administrators told him there would be no more discipline, he got a mark on his permanent record that carries the same level of violation as assault and hazing.

“Why are we so hell-bent on attacking queer students for standing up for our rights and demanding change?” he said in a video on the social media app TikTok. “It’s exhausting.”

Jack Petocz:Flagler teen activist works toward ‘more inclusive future’

At Winter Park High near Orlando, junior Will Larkins hung up a banner that read “PRIDE BELONGS HERE” ahead of their school’s walkout. Within a day, it was torn down in several places, said Larkins, who is president of the school’s Queer Student Union.

During the walkout, a fellow student stomped and spit on a rainbow flag. The responsible students faced no accountability, Larkins said. An Orange County Public Schools spokeswoman declined to comment, citing student privacy laws.

‘Curly Hair’:Pine View class president uses euphemism for gay in graduation speech

A couple months after the protests, Zander Moricz, the first openly gay class president at Sarasota County’s Pineview School, was told he couldn’t mention his queer activism during his graduation speech.

Students at Lyman High in Seminole County dedicated space in the yearbook to coverage of their school’s walkout. Just before the yearbooks were set to be distributed, administrators told them to cover some of the photos with stickers because they “did not meet school board policy,” the principal said in a message to parents.

Viewing the decision as censorship, the students started a social media campaign with the hashtag #stopthestickers that picked up traction across the state. The next day, School Board members voted unanimously to abandon the plan.

“We all make mistakes,” said Vice Chair Abby Sanchez, according to the Orlando Sentinel. “As students, I am proud of you for bringing it to our attention.”

Despite the protests, and a swath of celebrities and businesses, including Florida’s beloved Walt Disney Company, joining the chorus of critics, lawmakers passed the bill March 8.

By the end of the month, with the stroke of DeSantis’ pen, it became law.

It had mixed reception among Floridians; a Florida Atlantic University poll of 532 people found that 43% of respondents opposed the bill and 37% supported it. The remaining 20% didn’t have an opinion.

Meanwhile, across the country, the Human Rights Campaign was tracking more than 300 bills the civil rights organization identified as harmful to LGBTQ people. HB 1557 was one of 24 across 13 states that became law.

Consequences for teachers

Abbie Garretson came home that day to her mother sobbing.

Her two moms had moved to St. Petersburg two decades ago after hearing that it was an up-and-coming gay-friendly city. She felt safe and supported as a kid at school, making two Mother’s Day cards and drawing both her moms in a family portrait assignment. Garretson herself came out in sixth grade with support from her family and community.

That’s why the bill came as such a shock. The day it passed, she hugged her crying mother, who told her, “It was supposed to be better for you.”

Garretson, 18, organized a walkout at Pinellas County’s Gibbs High. It drew hundreds of students, a few of them hecklers, but a majority backing up the cause. She graduated last month as salutatorian.

She felt lucky to go to a supportive school, but, as she heard about horror stories at other schools, it underscored how much the bill’s enforcement will depend on where you live in the state.

“It is going to be per county, per school, per area, depending on the beliefs of that general public,” she said. “There’s really very little that the school board and the schools and the teachers will get to do or say about it.”

That’s part of why one of Garretson’s teachers who was especially supportive of queer students left the profession altogether. There was no breaking point for Ariel Ringo, a now-former Gibbs research and English teacher who is part of the queer community. But HB 1557 was another in a long line of state and district mandates that wore her down over her six years at Gibbs.

“I don’t want to have my whole life where … you’re dedicating your life and your time and your energy and you are so passionate about it, but the people in power don’t treat you like a professional and don’t trust you and don’t give you the respect you deserve,” Ringo, 31, said.

She quit last month and is moving to Michigan, where she’s hoping to work for an organization supporting queer youth.

Ringo wasn’t the only one. An Orlando area middle school science teacher told NBC News in April that he was leaving his 11-year teaching career after a group of parents demanded “consequences” against him for acknowledging his marriage to a man.

A Miami-Dade fourth-grade teacher told the same news outlet that after the bill passed, she quit. It would force her, a lesbian, back in the closet, she told NBC, “and I don’t think I can bear to see the students struggle and ask me about these things and then have to deny them that knowledge.”

Some supportive teachers who have stuck around have faced backlash.

In April, a St. Johns County teacher was asked to remove a T-shirt that read “Protect Trans Kids” after a parent complained to the principal, the St. Augustine Record reported. A few weeks later, in Lee County, a middle school art teacher was fired after someone complained that she had been teaching about various pride flags and told students she was pansexual, according to the Fort Myers News-Press.

At an Orange County school district training this month, attorneys cautioned K-3 teachers against discussing their partners in case it could be construed as violating the law, spokesman Michael Ollendorff said. They were also advised to remove stickers denoting their classrooms as safe spaces to LGBTQ students so that “instruction did not inadvertently occur on the prohibited content of sexual orientation or gender identity,” Ollendorff said.

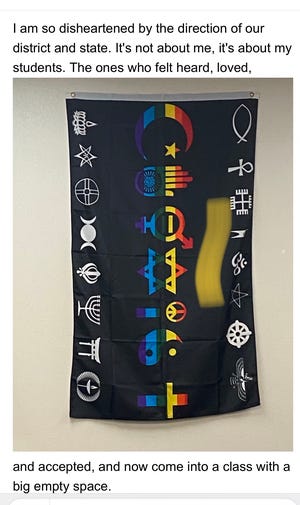

Educators at a Sarasota County high school were told to remove flags, posters and other possible “political” messaging, including one teacher’s “COEXIST” flag, the Sarasota Herald-Tribune reported.

“I am so disheartened by the direction of our district and state. It’s not about me, it’s about my students,” the teacher wrote on Facebook, “the ones who felt heard, loved, and accepted and now come into a class with a big empty space.”

More:Collier Commission candidate Chris Hall’s comments on schools, sexuality draw critics

On Facebook, the administrator of a Bay County government watchdog group lambasted the school district’s communications director, Sharon Michalik, for listing her pronouns in her email signature. It has become a more widespread practice in recent years to inform others of your gender and to be inclusive of all gender identities.

“By becoming the center of controversy and embracing leftist ideology, Mrs. Michalik diminished her ability to effectively communicate the policies of Bay District Schools,” said Jon Ward, who started the political group Bay County Taxpayers last year to protest a proposed school district tax increase.

Michalik said in a statement that she “had no idea that my decision to add my preferred pronouns to my automatic email signature a year ago could become such a distraction from the important work we’re doing for the children in our community as public school educators.”

She said she decided to remove the pronouns from her email after the social media uproar. She declined further.

Glimpses of hope

Despite the rough end to the school year, students around the state have found glimpses of hope and support.

For Larkins, school got easier after the walkout. Fewer people bullied them, and students who weren’t previously invested in LGBTQ issues got involved, Larkins said.

“People who were previously neutral became allies,” they said. “It showed we were the majority, and that perceived power shift is what I think changed things.”

Garretson, Larkins, Petocz and a fourth Florida student, Javier Gomez, were recognized for their advocacy work with a national Webby award for Social Movement of The Year. Gomez and Petocz were later invited to the White House to stand with President Joe Biden as he signed an executive order to protect queer youth.

Student activists around the state formed a group messaging chat to keep in touch and continue organizing. Larkins found support in a prior class of student activists: the Parkland shooting survivors who started the March for Our Lives movement.

Weinstein, the Palm Harbor University High teen, was relieved to graduate in May. He’s planning to attend the University of South Florida St. Petersburg Campus, which he said is “very, very queer-accepting.”

But he worries for the next generation of students.

He’s especially concerned for transgender students like him, who are facing threats to their access to gender-affirming healthcare and are left out of campaigns like Don’t Say Gay, which refer to sexual orientation but not gender identity.

Like many queer students, he found refuge at school, in his theater class, where he came out for the first time and saw his correct name listed on show programs. He advises underclassmen to find their own version of theater.

“There will always be a space for you,” he tells them. “You just gotta find it.”

He believes the teachers who supported him will continue to help future generations of LGBTQ students — until a parent or other party complains that it violates HB 1557.

After that, he’s not so sure.

Resources for queer students

Wolf, the Equality Florida press secretary, said students can share your story with the organization at freetosaygay.org.

LGBTQ youth are four times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers “because of how they are mistreated and stigmatized in society,” according to the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for LGBTQ youth.

To reach a Trevor Project mental health counselor:

Kathryn Varn is statewide enterprise reporter for the Gannett/USA Today Network – Florida. You can reach her at kvarn@gannett.com or (727) 238-5315.