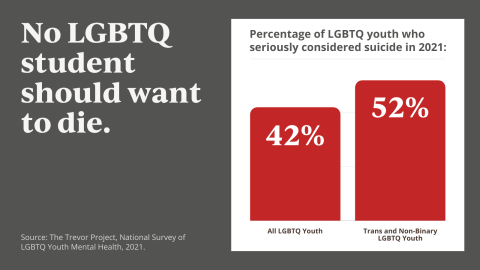

Last year, nearly half of LGBTQ youth seriously considered killing themselves, including more than half of trans youth, according to new data from The Trevor Project.

These figures reveal a deadly, mental-health crisis among high school and college-age LGTBQ youth of all races, which has been worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic and by recent, political attacks on LGTBQ students by state legislators across the nation.

“The [Trevor Project] study is actually on my computer screen right now to send it to my colleagues,” says Florida high school teacher Michael Woods, whose state recently passed a law that enables parents to sue school districts for teaching LGBTQ-positive curriculum. “Especially here in Florida, with the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ law, which should also be called ‘Don’t Say Trans,’ we have a lot of kids in stress,” he says.

The study, which involved 35,000 LGBTQ high school and college-age youth, of various races and identities, also shows how schools and colleges can help. A little more than half of LGBTQ youth identified their school or college as “an LGBTQ-affirming space”—and those students reported lower rates of attempted suicide. Even something as simple as using the correct pronouns—the ones that match students’ gender identify—can decrease suicidal ideas.

“Small steps can make a big difference,” says Joe Bento, a Seattle high school teacher who also is chair of the Washington state chapter of GLSEN, a national organization that helps educators make schools more affirming for LGBTQ students.

Take the NEA pledge against hate and bias!

The Pandemic: Making Everything Worse

The Trevor Project data shows how things have gone from bad to worse for LGBTQ youth in the past two years. In 2019, 40 percent of LGTBQ seriously considered suicide; in 2021, the rate hit 45 percent.

And it’s even scarier among students of color. About one in five Black LGBTQ students attempted suicide last year, as did a slightly higher rate of Indigenous LGBTQ students.

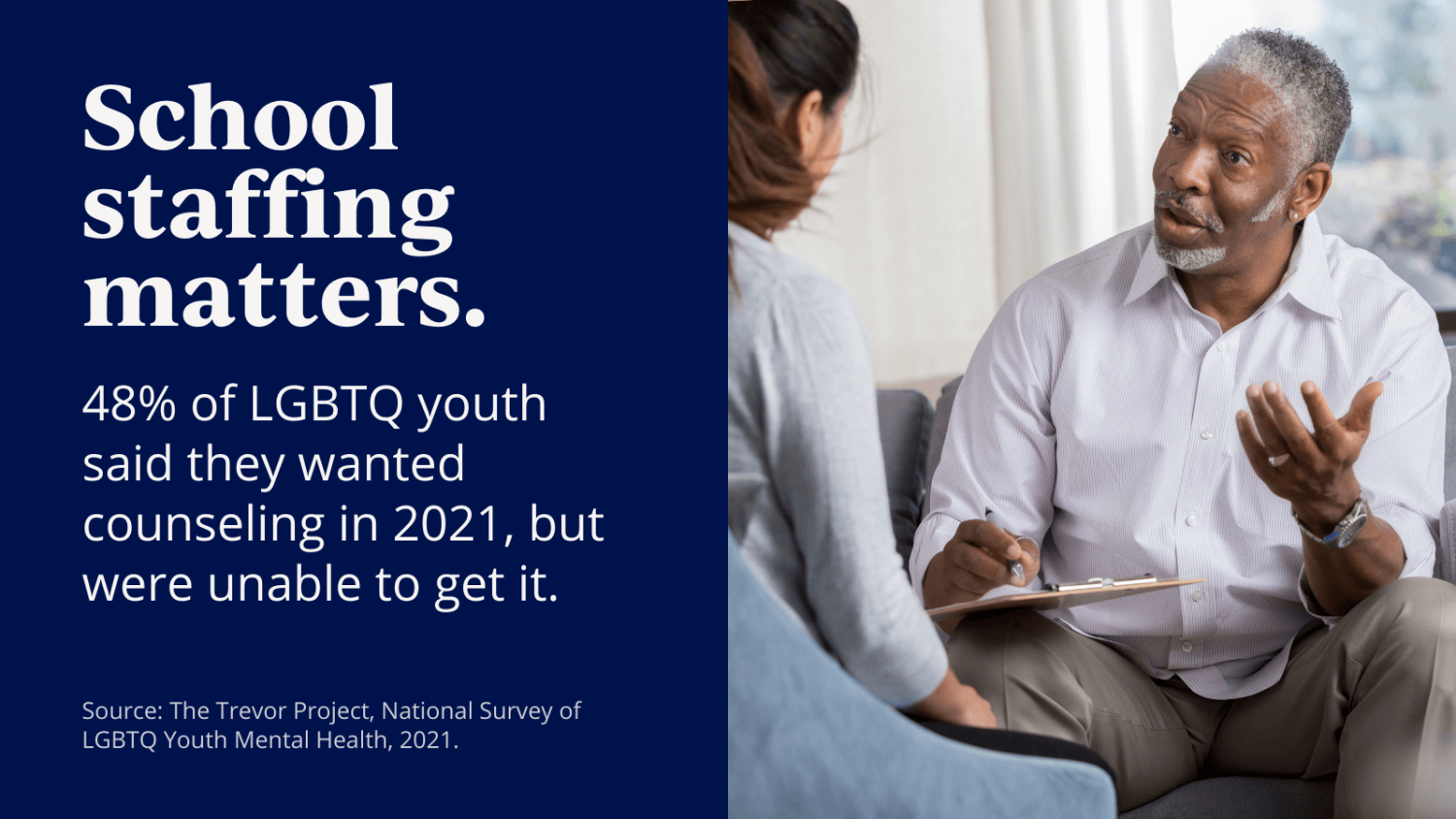

Meanwhile, mental-health care is scarce. Nearly half of LGBTQ youth—and more than half of Latino LGBTQ students—told the Trevor Project that they wanted counseling and didn’t get it.

The pandemic is an obvious factor, educators say. When colleges and schools switched to virtual learning, many LGBTQ students were closeted in homes where their identities are hidden. (Only 1 in 3 LGBTQ youth said they have LGBTQ-affirming homes.) These students may have lost access to counselors or other supports, like a Gay-Straight Alliance or Gender-Sexuality Alliance (GSA) club.

“For a lot of queer students, school is their safe space,” says Bento. “For a year and a half, they weren’t in that safe space.”

Now, students are back on campuses, in school buildings—but that doesn’t mean everything is okay, notes Bento. After two years of pandemic-related isolation and trauma, students desperately need mental-health support “When we got back, that didn’t necessarily happen,” he says. “Suddenly it’s state testing! And it’s this, this, this! Everything is ‘back to normal,’ but normal was garbage.”

Many students are suffering. But it’s almost always the most marginalized students who have the least access to mental-health supports, Bento points out.

Legislative Attacks on LGBTQ Students

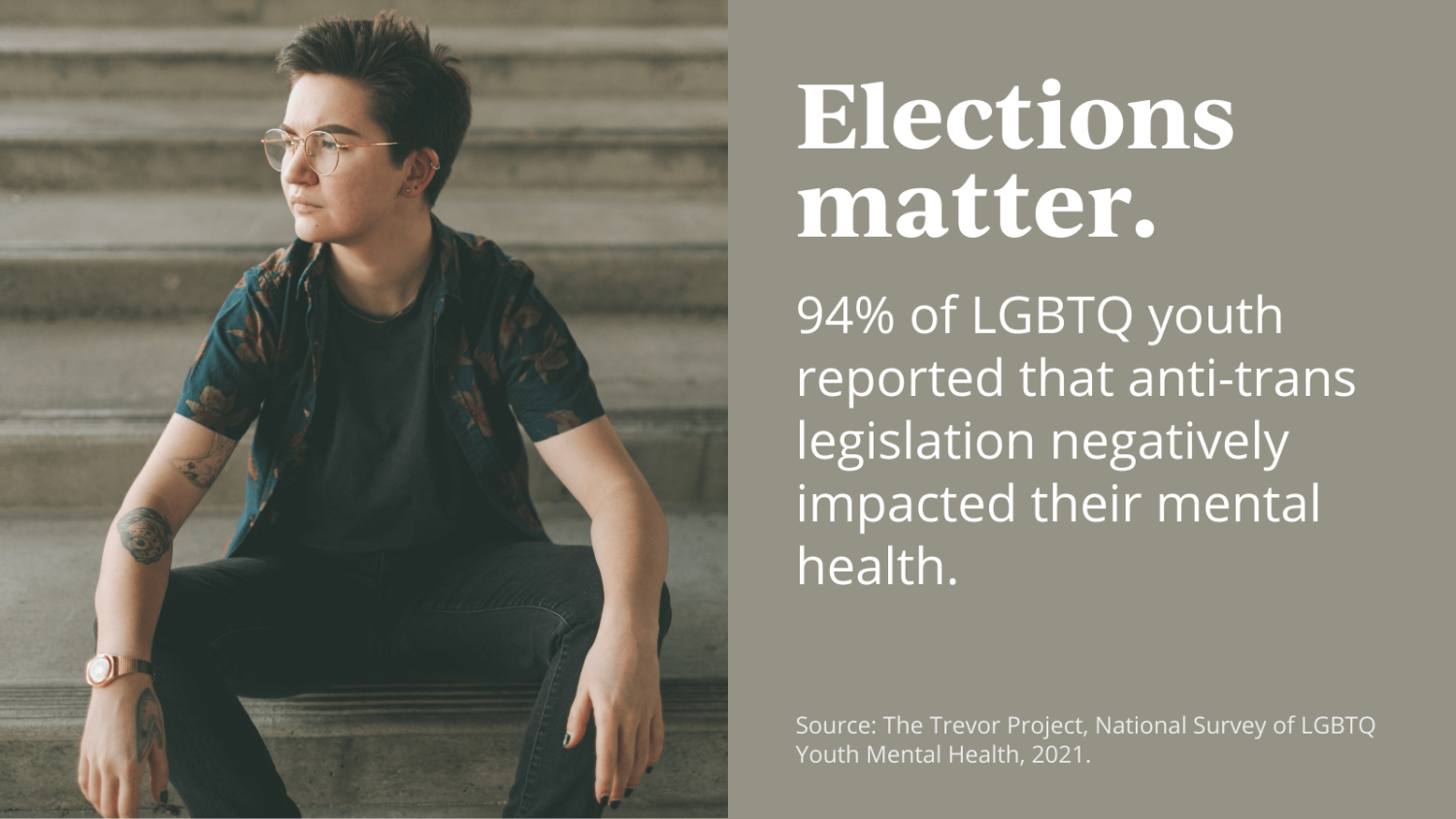

It’s not just the pandemic. Making matters worse for LGBTQ students, nearly 240 anti-LGBTQ bills have been filed this year in state legislatures, most of them targeting trans people, according to an NBC News analysis.

Many of these bills have been signed into laws that ban trans women and girls from participating in high school sports, prohibit trans students from using school bathrooms and locker rooms that match their gender identity, and restrict LGBTQ-positive school curriculum. For example, Florida’s new law enables parents to sue districts if they think their child has had inappropriate instruction on gender and sexuality. The cost of litigation will be borne by districts, which already are removing curricula.

LGBTQ students are very aware of laws that seek to harm them, educators say—and it causes them anguish. “They’re just coming back to the rigors of school [after the pandemic]—and now this!” says Woods.

NEA and its affiliates strongly oppose these laws. This spring, NEA President Becky Pringle wrote an open letter to Florida students, published in the Sun-Sentinel newspaper. “From protests to walkouts, you are bravely showing these politicians that you aren’t afraid to stand up for yourselves…To our students in Florida and elsewhere: We see you! We hear you! We are with you!”

For his part, Woods, an educator of 29 years, isn’t afraid either. He wears his “We’re All Human” t-shirt and answers his students’ distressed questions. But he worries about younger teachers with less job security, living in more conservative areas. Many may feel like they can’t be the educators that students need.

“When young people don’t feel like they have anywhere to turn or anyone to talk to… well, I know why the stats are the way they are,” he says.

What Can Schools and Educators Do?

NEA members and their unions are working hard to get more supports for students. In St. Paul, Minn., educators went to the brink of striking this spring to protect the presence of mental-health teams in every St. Paul school. Other K12 unions—like in Natrona County, Wyo.—are making sure federal pandemic-relief funds are spent to hire more school counselors and other professionals.

Recently, the Biden administration urged colleges and universities to do the same with their money.

But it’s also possible for individual educators to create affirming spaces in their offices, classrooms, buses, and other spaces. “Words matter,” says Bento, who introduces himself to his students like this: “My name is Mr. Bento. I use he/him pronouns.”

Safe space posters are great at signaling that you support your LGTBQ students but may not be allowable in all places. “In those places, you can still put something on your body, like a lanyard,” says Bento. (The NEA LGBTQ caucus, of which Bento is a member, offers “Safe Person, Safe Space” cards for educators to put in their lanyards.)

Bento uses the word “partner,” instead boyfriend or girlfriend, a subtle nod to the fact that not every relationship looks the same and that some students may not identify as male or female. “Think about who is not represented [in your words, in your curriculum],” urges Bento.

Yes, curriculum matters, too. (See GLSEN’s inclusive curriculum resource.) “Students need curriculum that reflects who they are, they need positive representation,” says Bento. “And not just Harvey Milk! Not just the AIDS epidemic! Where’s the joy?”

In fact, The Trevor Project asked LGBTQ youth the same question: “Where do you find joy?” The responses can guide educators in creating better spaces for all students. Answers include:

- Learning about LGBTQ history

- Learning I’m not alone and there are more people like me

- Supportive teachers

- Having a safe space to express gender, gender identity, and sexuality

- LGBTQ clubs on campus

- Living as their authentic self