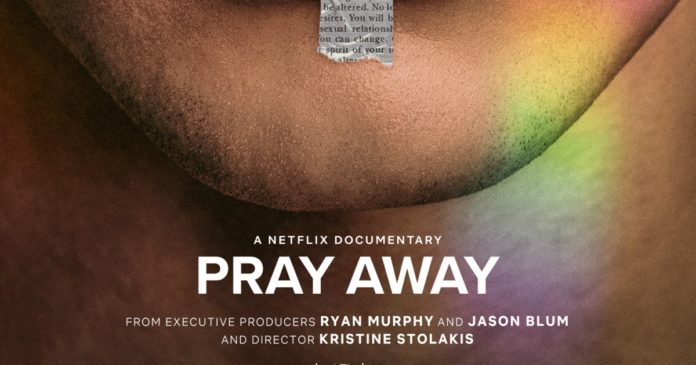

When American documentarian Kristine Stolakis set out to make her debut feature film, she knew she wanted to shine a light on the “ex-gay” movement, which consists of those that believe a person’s gender identity or sexual orientation can be changed.

But the idea — which was born out of the grief of losing her beloved uncle who had come out as transgender as a child and was a subsequent survivor of “conversion therapy” — did not begin to crystallize until she uncovered an unsettling truth about the enduring nature of the movement.

“I went from someone who was in a lot of pain, trying to make sense of what has happened to a family member, to a filmmaker who felt very determined to make a film when I discovered that the vast majority of conversion therapy organizations are actually run by LGBTQ individuals themselves, who claim that they, themselves, have changed and that they know how to teach others how to do the same,” Stolakis told NBC News.

Armed with a production team comprised of predominantly LGBTQ individuals — many of whom grew up in the evangelical church, survived conversion therapy or both — Stolakis sought to “ground the film in the undeniable truth that this movement, no matter the good intentions or reason for getting involved that any leader has, causes tremendous harm for people.”

“…this really is a movement of hurt people hurting other people, of what internalized homophobia and transphobia looks like when it is wielded outward.”

Kristine Stolakis

The result was the creation of a 100-minute documentary called “Pray Away,” which has received rave reviews from critics and debuts Tuesday on Netflix. Shot before the Covid-19 pandemic, the film chronicles the rise — and subsequent fall — of Exodus International, a conversion therapy organization that, according to the team behind the the film, began as a Bible study group in the 1970s consisting of five evangelical men who were looking to help one another leave the “homosexual lifestyle.” At its peak, the group reportedly had 400 local ministries across 17 countries.

But years after rising to stardom in the religious right, many of these “ex-gay” leaders, whose own same-sex attractions never went away, have since come out as LGBTQ and disavowed the very movement that they helped to grow. Stolakis’ list of interviewees in “Pray Away” includes Randy Thomas, the final vice president of Exodus International; Yvette Cantu Schneider, the former head of Exodus’ women’s ministries; and John Paulk, one of the most best-known “ex-gay” people in the world.

“Something my team and I talked about a lot in making this film is, this really is a movement of hurt people hurting other people, of what internalized homophobia and transphobia looks like when it is wielded outward,” said Stolakis, whose other directorial credits include “The Typist” and “Where We Stand.” “That was something we talked about so much in the crafting of this film, and that wasn’t to explain away people’s actions or to excuse their actions. We do not shy away in this film from the fact that leaders of this movement cause pain.”

While many former leaders have renounced and spoken out against the “pray the gay away” movement, Stolakis said “the larger culture of homophobia and transphobia,” particularly in religious communities, has allowed the movement to continue with younger leaders, even with the dissolution of Exodus International in 2013 and the legalization of same-sex marriage in the U.S. in 2015.

“It doesn’t matter if a few people defect, because there’s always going to be someone who’s going to be ready and motivated to believe that change is possible,” she said. “The movement is alive. In some ways, it is thriving. It continues on every major continent in our world.”

In the U.S. alone, nearly 700,000 lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults have been subjected to some form of conversion therapy during their lifetime, according to a 2019 report from the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law. The controversial practice, however, has been condemned by a long list of medical and mental health organizations, including the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association, and it is now prohibited from being practiced on minors in at least 20 states.

Regardless of religious or political affiliation, there are a number of common misconceptions about conversion therapy, including the belief that it only consists of “aversion treatments,” such as applying electric shocks.

“The vast majority of conversion therapy actually looks more like talk therapy and often happens with either a licensed counselor, or more often with a spiritual or religious leader that acts as a pseudo-counselor,” Stolakis said. This misconception, she continued, “makes it so that people who are practicing conversion therapy don’t even realize that they’re practicing it.”

“Or more insidiously, people who are practicing conversion therapy use that stereotype to say, ‘That’s not what we’re doing. We’re not shocking anybody,’” she added. “Talk therapy might, on the surface, look less damaging, but in the end, however you’re taught to hate yourself is going to have horrible mental health consequences.”

“The real problem is that the movement sends a message that being LGBTQ is a sickness and a sin, and the only way to be healthy is to be straight and cis.”

Kristine Stolakis

In order to contextualize the lingering effects of conversion therapy on younger generations, Stolakis and her team felt that it was imperative to include two contrasting voices, including one that directly contradicted their own views on the subject. They eventually settled on Julie Rodgers, a millennial survivor of the movement, and Jeffrey McCall, a self-identified “formerly transgender” person and a proponent of anti-LGBTQ legislation.

In Rodgers, Stolakis found a woman who, from the time she was 16, “experienced the movement primarily from the point of view of having participated — not having been, for the most part, in a position of leadership.”

“We return to her story throughout, which evolved into a story of self-hatred and self-harm, because that is the reality of this movement,” she said. “That self-hatred manifests itself in so many dark and horrible ways that hurt people.”

A report published last year in the American Journal of Public Health found that young people who had been subjected to conversion therapy “were more than twice as likely to report having attempted suicide and having multiple suicide attempts” than those who were not subjected to the controversial practice.

Stolakis interviewed Rodgers over the course of two days, dedicating the first to asking her about the most difficult parts of her past in painstaking detail. The experience, Stolakis said, allowed everyone involved to organize their own mental health resources and helped to develop a sense of trust on both sides of the camera that is crucial to documentary filmmaking.

“We were all very forthright about the fact that this was going to be a film that would be critical of the movement,” she explained. “I was forthright about the fact that I had a family member that went through this, and that was something that was professed out loud in my interviews with former leaders and the survivor of conversion therapy in our film. I actually think, often, that’s when the most ethical filmmaking happens — when you and your team have a real stake in the community that you’re covering — and that was quite true for us.”

For Stolakis, being honest and upfront about her intentions as a filmmaker were extremely important in her initial conversations with McCall, who she said was always a willing participant.

“We promised not to put words in his mouth, and that was easy to do, because I know that Jeffrey believes what he’s doing is right,” Stolakis said. “I also know that gender fluidity is real, so the way that he identifies as previously trans and now cis is not actually the real crux of the problem of this movement.

“The real problem is that the movement sends a message that being LGBTQ is a sickness and a sin, and the only way to be healthy is to be straight and cis. That’s really the message that harms people in the deepest ways,” she continued. “It really is something that he trusted us, and we really disagree about the consequences of his actions quite deeply, but I am thankful that he participated.”

Having witnessed the harmful effect that conversion therapy has had on her own family, Stolakis’ initial research also helped her to understand her uncle’s lifelong struggles with depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, addiction and suicidal ideations, which are “all very common for people that go through something like this,” she said.

“That, for me, was such a lightbulb moment, because it helped me understand why my uncle had believed for his entire life that change was possible, that change was right around the corner,” she said. “And you can understand his devastation and his self-blame when he, of course, never changed.”

A 2019 study published in JAMA Psychiatry that looked specifically at gender identity conversion efforts found that such efforts are associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including suicide attempts.

Stolakis has grown to understand that her late grandparents, the people who sent her uncle to a therapist to treat his “gender problems” in the ’60s and the early ’70s, “had a lot of professional people — his doctor, his guidance counselors — telling them that they were doing the right thing.”

“What I’d love to say, enthusiastically and on the record, is my grandparents were some of the best people I knew,” she declared. “They loved my uncle so much, and as decades went on, they actually became completely affirming and supportive of my uncle. But my uncle had spent so much time being told this lie — that being trans was a sickness and a sin — that he started to believe it himself. And it was very hard for him to accept himself, and he became celibate his entire life.”

In recent years, Stolakis and her family have made some peace with just how difficult her uncle’s life had been and the reality that his experience was far from an isolated or a dramatic bad case.

“He wasn’t a weak person; he wasn’t a person that was meant to be sick,” she elaborated. “He was a strong, smart, really loving person who got a message said to him over and over again that something was deeply wrong with him, that he was sick. It had nothing to do with him, and I think that’s really given my family some healing.”

With “Pray Away” set to debut in more than 190 countries on Netflix this week, Stolakis wants to make one thing clear to every prospective viewer: The “ex-gay” movement was never led by just “a couple of bad apples.”

“As long as that larger culture of homophobia and transphobia exists — be it in our churches, any religious community, our political sphere or our culture — some version of conversion therapy and the ex-LGBTQ movement will continue,” she explained. “I think if we understand how it works in this world, then we have a lot more tools at our disposal to try to meaningfully end this movement once and for all.”

“Pray Away” is now streaming on Netflix.