Russia invades Ukraine

The global science community was quick to condemn Russian’s invasion of Ukraine in February. Research organizations moved fast to cut ties with Russia, stopping funding and collaborations, and journals came under pressure to boycott Russian authors.

The situation escalated when Russian forces attacked Europe’s largest nuclear power plant, Zaporizhzhia, in March, prompting fears of a nuclear accident. Russian troops continue to occupy the power plant. Since the invasion began, thousands of civilians have been killed and millions displaced; many others, including scientists, have fled the country.

The war has affected research in space and climate science, disrupted fieldwork and played a significant part in the global energy crisis. The invasion could also precipitate a new era for European defence research.

JWST delights astronomers

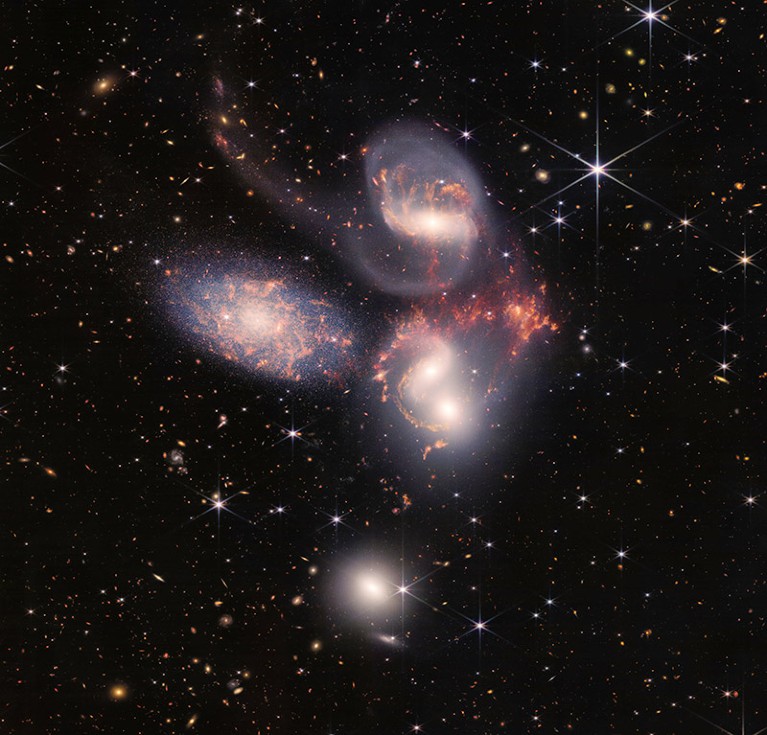

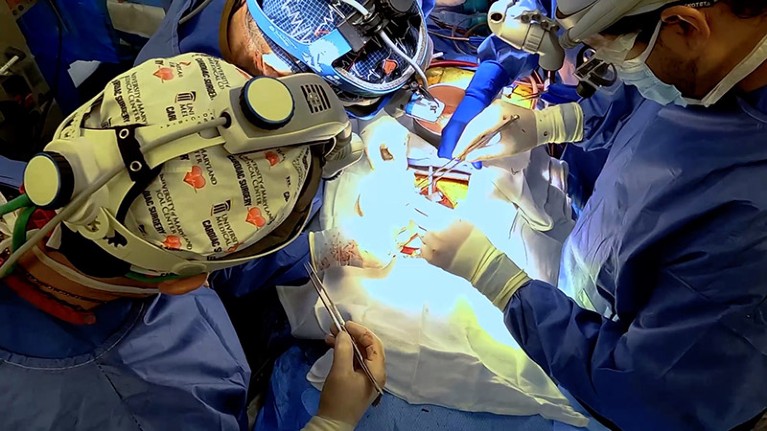

Stephans Quintet, a grouping of five galaxies, taken by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI via Getty

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — the most complex telescope ever built — reached its destination in space in January after decades of planning. In July, astronomers were awed by the telescope’s first image — of thousands of distant galaxies in the constellation Volans. Since then, the US$10-billion observatory has captured a steady stream of spectacular images, and astronomers have been working feverishly on early data. Insights include detailed observations of an exoplanet, and leading contenders for the most distant galaxy ever seen.

NASA also decided not to rename the telescope, despite calls from some astronomers to do so because the telescope’s namesake, a former NASA administrator, held high-ranking government positions in the 1950s and 1960s, when the United States systematically fired gay and lesbian government employees. A NASA investigation “found no evidence that Webb was either a leader or proponent of firing government employees for their sexual orientation”, the agency said in a statement in November.

AI predicts protein structures

Researchers announced in July that they had used the revolutionary artificial-intelligence (AI) network AlphaFold to predict the structures of more than 200 million proteins from roughly one million species, covering almost every known protein from all organisms whose genomes are held in databases. The development of AlphaFold netted its creators at the London-based AI company DeepMind, owned by Alphabet, one of this year’s US$3-million Breakthrough prizes — the most lucrative awards in science.

AlphaFold isn’t the only player on the scene. Meta (formerly Facebook), in California, has developed its own AI network, called ESMFold, and used it to predict the shapes of roughly 600 million possible proteins from bacteria, viruses and other microorganisms that have not been isolated or cultured. Scientists are using these tools to dream up proteins that could form the basis of new drugs and vaccines.

Monkeypox goes global

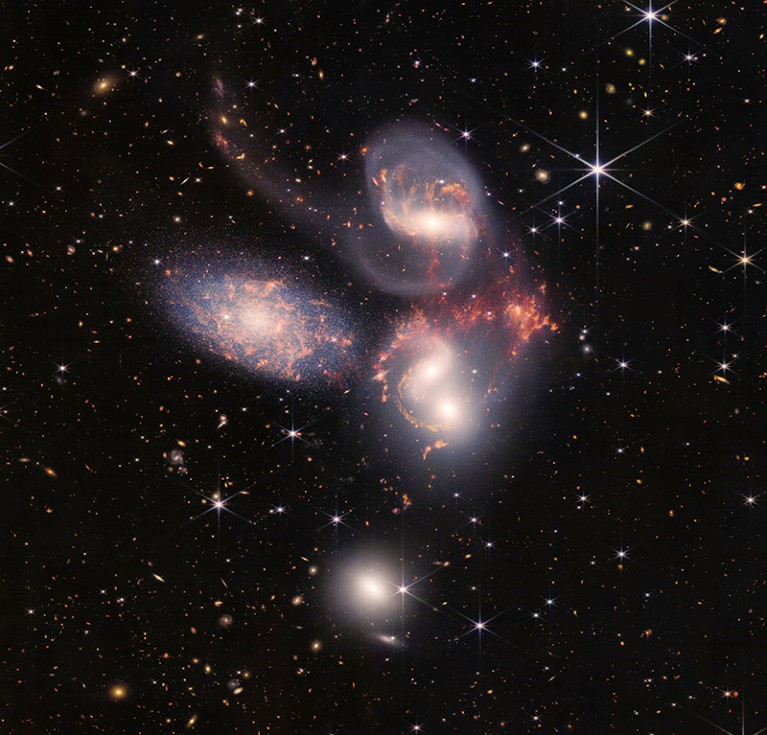

The monkeypox virus (shown here as a coloured transmission electron micrograph) is related to the smallpox virus.Credit: CDC/Science Photo Library

The rapid global spread of monkeypox (recently renamed ‘mpox’ by the World Health Organization) this year caught many scientists off guard. Previously, the virus had mainly been confined to Central and West Africa, but from May this year, infections started appearing in Europe, the United States, Canada and many other countries, mostly in young and middle-aged men who have sex with men. The virus is related to smallpox, and the circulating strain only rarely causes severe disease or death. But its fast spread led the World Health Organization to declare the global outbreak a ‘public-health emergency of international concern’, the agency’s highest alert level, in July.

As cases soared, researchers got to work trying to understand the dynamics of the disease. Studies confirmed that it is transmitted primarily through repeated skin-to-skin contact, and trials of possible treatments got under way. Existing smallpox vaccines were also used to suppress the virus in some countries. Six months after mpox infections first started increasing, vaccination efforts and behavioural changes seemed to have curbed its spread in Europe and the United States. Researchers predict a range of scenarios from here — the most hopeful being that the virus fizzles out in non-endemic countries over the next few months or years.

The Moon has a revival

The Moon has become a popular destination for space missions this year. First off the launch pad, in August, was South Korea’s Danuri probe, which is expected to arrive at its destination in January and orbit the Moon for a year. The mission is the country’s first foray beyond Earth’s orbit and is carrying a host of experiments.

Last month, NASA’s hotly anticipated Artemis programme — which aims to send astronauts to the Moon in the next few years — finally kicked off with the launch of an uncrewed capsule called Orion, a joint venture with the European Space Agency. As part of a test flight to see whether the system can transport people safely to the Moon, the capsule flew out past the Moon and made its way back to Earth safely this month.

A lunar spacecraft made by a Japanese company launched this month. ispace’s M1 lander is aiming to be the first of several private ventures to land on the surface of the Moon next year. The lander will carry two rovers, one for the United Arab Emirates and another for the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA. The rovers will be a first for both countries.

Climate-change funding

People cross a flooded highway in Sindh province, Pakistan in August.Credit: Waqar Hussein/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

There were many reasons to feel despondent about the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP27) in Egypt last month, but an agreement on a new ‘loss and damage’ fund was one bright spot. The fund will help low- and middle-income countries to cover the cost of climate-change impacts, such as the catastrophic floods in Pakistan this year, which caused more than US$30 billion worth of damage and economic losses.

But calls at COP27 to phase out fossil fuels were blocked by oil-producing states, and many blamed the lack of progress on the energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. High natural-gas prices have led some European nations to rely temporarily on coal. Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels are expected to hit 37.5 billion tonnes this year, a new record. The window to limit warming to 1.5–2 ºC above pre-industrial temperatures is disappearing fast — and might even have passed.

Omicron’s offspring drive the pandemic

Omicron and its descendants dominated all other coronavirus variants this year. The fast-spreading strain was first detected in southern Africa in November 2021, and quickly spread around the globe. From early on, it was clear that Omicron could evade immune-system defences more successfully than previous variants, which has meant that vaccines are less effective. Throughout the year, a diverse group of immune-dodging offshoots of Omicron has emerged, making it challenging for scientists to predict coming waves of infection.

Vaccines based on Omicron variants have been rolled out in some countries in the hope they will offer greater protection than previous jabs, but early data suggest the extra benefit is modest. Nasal sprays against COVID-19 have also become a tool in the vaccine arsenal. The idea is that these stop the virus at the site where it first takes hold. In September, China and India approved needle-free COVID-19 vaccines that are delivered through the nose or mouth, and many similar vaccines are in various stages of development.

Pig organs transplanted into people

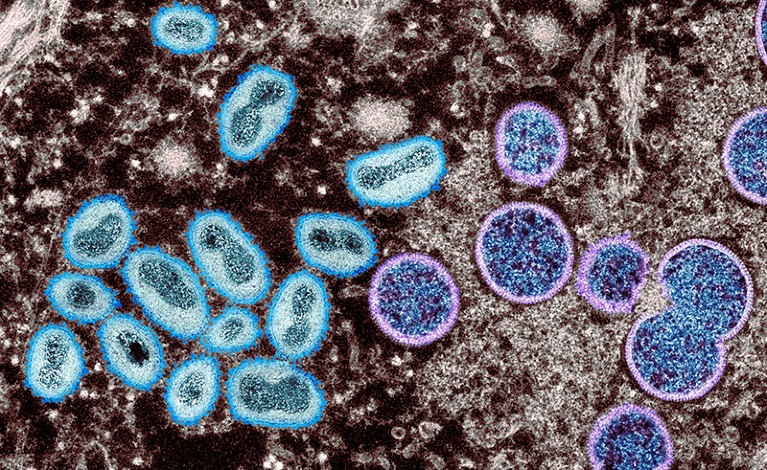

Surgeons in Baltimore, Maryland transplanted the first pig heart into a person in January.Credit: EyePress News/Shutterstock

In January, US handyman David Bennett became the first person to receive a transplanted heart from a genetically modified pig — a crucial first step in determining whether animals could provide a source of organs for people who need them. Bennett survived for another eight weeks after the transplant, but researchers were impressed that he lived for that long, given that the human immune system attacks non-genetically modified pig organs in minutes. A few months later, two US research groups independently reported transplanting pig kidneys into three people who had been declared legally dead because they did not have brain function. The organs weren’t rejected and started producing urine. Researchers say the next step is clinical trials to test such procedures thoroughly in living people.

Elections and science

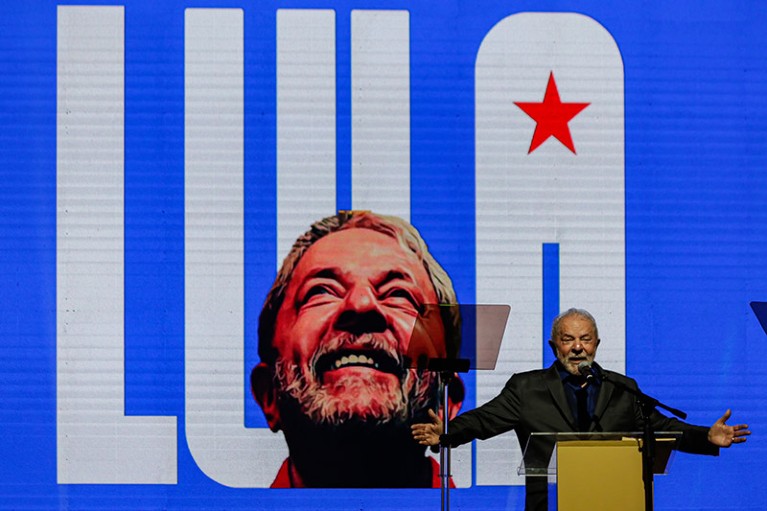

Luís Inácio Lula da Silva was elected president of Brazil in October.Credit: Fabio Vieira/FotoRua/NurPhoto via Getty

National elections in Brazil, Australia and France brought relief for many researchers. After three years of science-damaging policies under right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil narrowly elected leftist labour leader and former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to lead the country in October. Scientists are hopeful that Lula’s return will result in a desperately needed boost to research funding and greater protection for the Amazon rainforest.

French researchers were buoyed by President Emmanuel Macron’s victory over far-right candidate Marine Le Pen in April, and the election of Anthony Albanese as prime minister in Australia in May was seen as a good thing for science and climate-change action, too. In China, Xi Jinping cemented his legacy with an historic third term as head of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi has placed science and innovation at the heart of his country’s growth strategy.

In other nations, it was unclear how research would fare under new leaders, such as Giorgia Meloni, the far-right candidate elected as Italy’s first female prime minister in October. Science was not a priority for the United Kingdom’s three prime ministers this year, although they have retained previous commitments to raise research funding. After Boris Johnson reisgned, Liz Truss was in the position for just seven weeks before she too resigned and the current Prime Minister Rishi Sunak took over.

Environmental push begins

This week, conservation and political leaders are attempting to finalize a global deal to protect the environment. The UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity Conference of the Parties (COP15) is under way in Montreal, Canada. A new biodiversity treaty, known as the post-2020 Global Diversity Framework, has been delayed by more than two years because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Progress towards an agreement has been slow, and the deal looked under threat when negotiations stalled over financing during international talks in Nairobi in June. Financial pledges from some nations to support biodiversity helped discussions to move forward, but estimates suggest that US$700 billion more is needed annually to protect the natural world. At the meeting, delegates will hopefully agree on targets to stabilize species’ declines by 2030 and reverse them by mid-century.