But he does meet Gregory there, a New York native who has been making it on his own since his mother kicked him out at age 15 for charging men to service him in the church bathroom. Gregory becomes Trey’s first guide to the city’s opportunities, hustles and, of course, its gay scene.

At the center of Trey’s experience is Mt. Morris Baths, a bathhouse in Harlem catering to mostly Black gay men. Here Trey begins not to discover his sexuality — he was long ago branded a “sissy” in his childhood in Indianapolis — but rather to revel in it. Back home, he had no real friendships, was bullied by other boys, never got to experience dates or parking or slow dancing in a gym for prom. But at Mt. Morris, he’s in his element: “being stalked into a dark corner of a bathhouse maze and submitting to the carnal demands of an aggressive man that you’ve never spoken to might seem like a strange substitute for the teenage mating rituals I missed out on,” Trey tells us, “but it had raw drama every inch as thrilling as schoolyard puppy love.”

As Trey becomes a regular, the bathhouse acts as a home away from home, where friendly intimacy exists as surely as the carnal kind. It is at Mt. Morris that he meets the civil rights movement legend Bayard Rustin, who becomes a sort of venerated teacher as well as a friend, although a footnote (one of many, more on that later) disclaims that there “is no evidence that Bayard Rustin (1912–1987) was a customer at the Mt. Morris Baths or any other gay bathhouse or sex club.” Regardless, the novel’s Rustin is comfortable in his sexuality and spends many days sitting naked in his towel and educating Trey in queer history and culture through conversation and book recommendations.

Rustin also opens Trey’s eyes to the AIDS crisis. Some readers will surely wonder how that’s even possible: Wasn’t being a gay man in New York City in the 1980s defined by the epidemic? Yes and no. As the majority of Americans can now attest, there’s a sort of cognitive dissonance in having a dangerous disease running rampant while also being required to continue living and working, with or without prophylaxis. It’s not that Trey didn’t know about it. It’s that he didn’t think much about it: “If the bald gay cashier who never charged me for gum stopped coming to work at the corner store, I didn’t wonder why. If I no longer crossed paths with the cute queer dogwalker on my way to the Strand Book Store, I figured he changed his route. I was blind to the magnitude of death and the politics responsible for so many lost lives until Rustin educated me.”

Formal or informal education can only go so far though, and Trey learns his most valuable lessons through trial and error. His enthusiasm, quick thinking and to an extent his youthful naivete lead him to spearhead a successful rent strike in his Fred Trump-owned building. On Rustin’s advice, he decides to get involved with the gay rights movement and is soon volunteering with Angie, a lesbian running an unofficial hospice for men dying of AIDS (a common practice at a time when poor gay men especially had nowhere else to go for care). While living openly as a gay man is meaningful to Trey, it’s his slow and steady entry into activism that gives him a sense of purpose.

“My Government Means to Kill Me” is written as if Trey is narrating or writing his story many years after the experiences described within, and the chapter headings take the form of lessons, such as “Lesson #1: The Boss Doesn’t Love You” or “Lesson #10: To Change the World, Have a Selfish Goal.” At one point, Trey admits that among Rustin’s recommended books, he’s able to grasp the biographies but has a hard time with political theory. It appears that the book in our hands is the one he wrote for young people like himself who may also need to learn even as they throw themselves into activist work. Who provided the annotations, which are full of historical context, is less clear. Even though they’re helpful — mainly to an audience less familiar with both Black and queer history — they aren’t utilized as well as they might be for a full metatextual effect. But that’s a small flaw in an otherwise marvelous read.

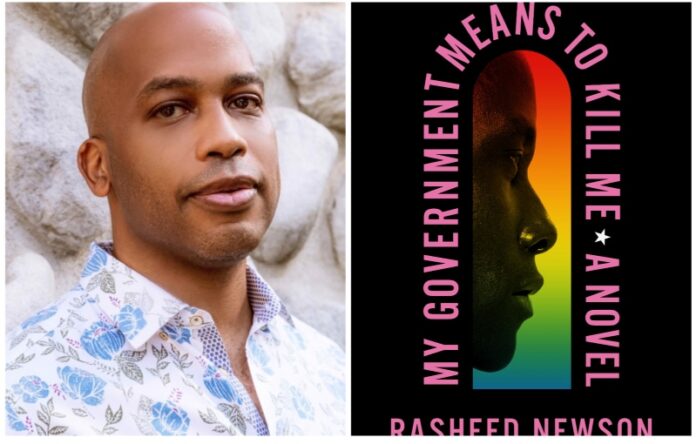

The book is also a love letter to activism, which isn’t to say it glamorizes it. Quite the opposite: Trey gets the dubious pleasure of having several of his elders and mentors disagree with one another, giving him advice from eras gone by or challenging his own sense of ethics. Newson, who is also a television writer and producer (“The Chi,” “Bel-Air”), beautifully portrays just how social activism has to be. Without people interacting — cheering each other on, caring for each other to avoid burnout, allying together for a cause and, yes, bickering about means and ends — there would be no social movements at all.

To the well-versed in the era’s politics, the many luminaries Trey meets and the historic events he finds himself at the center of might seem far-fetched, but there’s a sense that Newson is winking at those of us in the know, inviting us into that space of wondering what we might have done or failed to do if we had lived then and there. And as for the majority of readers, the book provides a crash course in the history of a pivotal era via a vividly imagined lived experience. Much like Trey being schooled by Rustin “with such a light touch,” readers of “My Government Means to Kill Me” may not even realize they’re “getting smarter about gay culture and politics.”

Ilana Masad is a critic and the author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

My Government Means to Kill Me

By Rasheed Newson. Flatiron. 288 pp. $27.99.

A note to our readers

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.