As I tore apart the living room of my late father’s San Francisco home, searching in vain for a will, I stumbled upon an artifact of my parents’ relationship that surprised me, though I now realize it shouldn’t have.

The wrinkled cocktail napkin was tucked inside a delicate metal chest resting on the hearth of Dad’s fireplace. On one side was a message to my mother, scribbled in blue ink. On the other, the South Carolina address where my mother had lived as a young woman in the early 1980s.

“Melissa,” my father wrote, “You have touched my life and I am blessed with love for you forever. Happy birthday, Davyd.”

I assume Dad used the napkin as practice for a card he sent to Mom. He held onto it for decades — even after Mom was no longer his wife.

The moment I discovered the napkin as I knelt on Dad’s sun-drenched floor that day last June, my eyes grew watery and my stomach tightened. Barely a day after his unexpected death, so much of what I thought I knew about my father’s life began to shift.

During my childhood, he always seemed different than my friends’ fathers. He drank Champagne and listened to Linda Ronstadt, and offered equally impassioned disquisitions on Judy Garland’s filmography, the Summer of Love and the 49ers. He packed my mother’s work lunches and brewed her coffee, which he never drank himself. But the few overtly romantic gestures I saw Dad perform — the exaggerated kiss here and there — appeared somehow half-hearted.

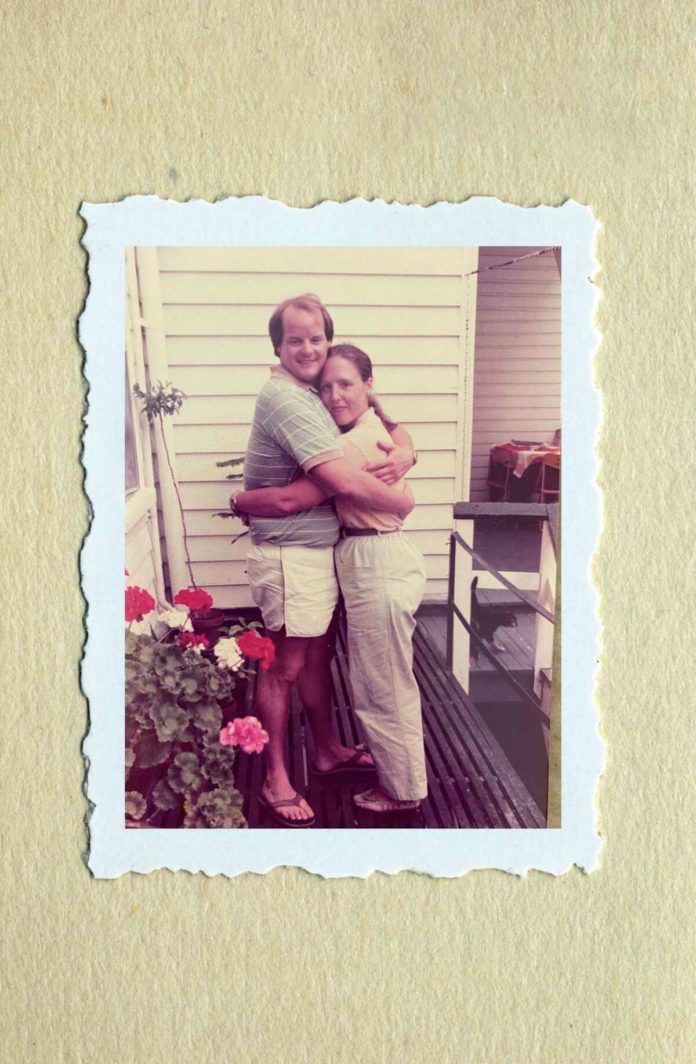

Above: Davyd Morris and Melissa Larsen in South Carolina in the 1980s. Top left: J.D. Morris (left), his brother, Alex, and his father, Davyd, at Coit Tower in the 1990s. Top right: Davyd Morris with Alex and J.D. in Corona Heights in 2020.

Chronicle collage with image provided by J.D. Morris / Getty Images/iStockphoto

In Salinas and Bakersfield, the places where my parents raised me, Dad was often a fish out of water. His interests skewed more cosmopolitan than those of most other stay-at-home parents and he leaped at seemingly every opportunity to take us out of town. In his native San Francisco, he was electrified — the world’s most enthusiastic tour guide. No trip to the city was ever long enough for him.

When I was 21, I thought I learned the truth that explained it all: My father was gay. Just like me and my older brother.

The revelation confounded me. Among everyone I’d met in both of my hometowns and all the friends I’d made in college at UC Berkeley, I could count on one hand the number of gay people I knew who also had a gay sibling. I did not know a single other person who had both a gay sibling and a gay parent.

I recoiled at the rarity — no one else was like us, it seemed, to my dismay. Again and again, I returned to the same desperate thoughts: Why can’t we be normal? Why can’t he be normal?

It was Dad’s shocking death on a Thursday morning that forced me to confront how wrong those ruminations were as I agonized over the conversations and shared experiences we would never have. The day of my fruitless search for his nonexistent will, I screamed so loud and for so long that my voice was hoarse for four days.

Dad spent the last eight years of his life in San Francisco, and for the final three, I lived here, too. We cherished our proximity to each other.

I could walk to his home from mine, a journey I frequently made to spend an afternoon talking about current events over one of his home-cooked meals. He would have me over to watch awards shows or to attend the small parties he hosted for holidays or San Francisco Pride. He would offer to pick me up in his car, and I would decline; I relished that I could reach him on foot.

I never asked him much about his past because I thought I knew his story already. He was a man who dated men in his 20s until he met a woman he loved, one with whom he tried to build a more socially acceptable life. After my parents grew apart and decided to end their marriage, Dad returned to his roots while Mom stayed in the Salinas Valley.

In the aftermath of his death, however, as I rummaged through everything he’d held onto over 65 years, the narrative I had constructed around my father grew more complicated.

Left: Davyd Morris at the top of Twin Peaks in the 1980s. Right: Davyd Morris and his sons, Alex and J.D., in Falls Church, Va., in 1992.

Chronicle collage with images provided by J.D. Morris / Getty Images/iStockphoto

In a box stuffed with faded photos and writings, Dad had stored two postcards he received in the 1970s at a Noe Valley address not far from my first San Francisco apartment. Both were from a friend I’d never heard of, who was apparently traveling in Europe at the time. In one postscript, the man gleefully referenced the location of a gay hookup spot in Rome.

Paradoxically, it might have seemed, Dad retained those queer keepsakes alongside fragments of his 30-year relationship with my mother — a pocket-size photograph of Mom in her 20s, the china they were gifted on their wedding day, and images of them in tender, candid moments captured decades ago by an old friend.

Among those items was a card Mom mailed to Dad on Aug. 10, 1983. “Dear Davyd,” she wrote, “Some things are meant to be … I love you forever — let’s grab it and run. Love, Melissa.” They married in Washington, D.C., less than two years later.

My younger self wouldn’t have believed my parents once exchanged such genuine romantic notes, or that Dad kept them in his living room years after the conclusion of their long divorce.

The sole conversation Dad and I ever had about his sexuality took place on a windy Monterey beach nine years ago, the month he and Mom split up. He had frustratingly little to say. I remember staring at the ground and digging my feet deep into the cold sand as I asked Dad why he had never raised the subject with me or my brother, because both of us had been out of the closet for several years by then.

Dad threw up his hands and proclaimed, “You never asked!”

He pointed out that, in 2008, he had taken our family on a whirlwind trip through the Castro during an unsuccessful attempt to grab tickets to see “Milk” at the Castro Theatre. He protested that I hadn’t asked him why he could so easily rattle off the names of long-gone businesses in one of the world’s most famous LGBTQ districts.

I wish I had told him that when he drove me down Castro Street and my 16-year-old eyes looked out the window, I couldn’t see his past because I saw my future instead. I was enthralled and confused and anxious all at once. It was overwhelming.

In hindsight, I understand Dad’s point. Although he’d never directly explained his hidden self to me, he’d tried to share his love for the places where that self was forged.

San Francisco has always been part of my life because of Dad, who was born in the city and raised on the Peninsula in South San Francisco. In 1993, the year after I was born, we scattered my paternal grandmother’s ashes west of the Golden Gate Bridge. Dad filled my childhood with trips to the Metreon, the Exploratorium, Ghirardelli Square and the Giants’ ballpark.

When I was in high school, he once pulled me out of swim practice early so he could take me to the city for a surprise. It wasn’t until we were on the road that he revealed we were on our way to see “Legally Blonde: The Musical” at the Golden Gate Theatre.

In my 20s, I came to know San Francisco much better on my own, particularly the Castro. Its crowded dance floors and lively bar patios beckoned to me on Saturday nights. As it turned out, my father felt similarly.

More than once, after he settled into a rental home near Corona Heights Park, I saw Dad while I was out in the Castro with friends. Those moments always made me uneasy. No one else I knew was bumping into their father at gay bars, so I tried to end the encounters as quickly as possible.

Left: Davyd Morris and son J.D. in San Francisco in 1993. Right: Davyd Morris and J.D. at Corona Heights Park in 2015.

Chronicle collage with images provided by J.D. Morris / Getty Images/iStockphoto

Though I never got used to the experience of colliding with him in those spaces, I viewed his proximity as a precious gift. The last time I saw him, just a few days before he died, we drank Champagne and ate homemade creme brulee on his couch while looking out at the pink triangle that adorns Twin Peaks every Pride Month. He complained that someone had swiped his Sunday edition of The Chronicle and we made plans for Father’s Day breakfast. Then I walked home.

Before my father’s ashes joined his mother’s in San Francisco Bay last August, we celebrated his life at the Great American Music Hall in the Tenderloin. We had a singer perform “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” and one of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence read an original poem inspired by Dad.

My family then spent a reminiscent evening in the Castro. Much to my surprise, Mom joined us — even inside Dad’s favorite watering hole, 440 Castro, a bar once fittingly called Daddy’s. While Mom followed the Giants game on her phone, one of the bartenders tearfully told me that he used to put them on TV for Dad.

A block away, at the corner of Castro and 18th streets that has represented a community memorial site for decades, my family hung a poster for Dad that remained for two weeks. It was made from photos of him in San Francisco: at the top of Twin Peaks in the 1980s, at Coit Tower with me and my brother in the 1990s, at Corona Heights Park with me in the 2010s. “Rest in peace, Davyd Morris,” the poster said. “You were so loved.” I underlined the last two words with a bright red marker.

Mom herself never eulogized Dad, but I later found the final note she left him in the funeral guest book.

“You are now at peace, the burdens of this life are gone,” she wrote. “Walk freely in heaven, my partner and friend.”

Only after his life’s abrupt end could I see Dad in the full context that had long evaded me. His years with my mother and the parts of him I did not know until later in life were not merely conflicting forces. They were two halves of a whole, and it was OK that Dad treasured both of them alike. Learning that he embraced his ostensibly warring identities with nostalgia allowed me, too, to appreciate them equally.

No one else was like us, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

J.D. Morris is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jd.morris@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @thejdmorris