This Disease Outbreak News on the multi-country monkeypox outbreak is an update to the previously published editions and provides an update on the epidemiological situation, further information on the use of therapeutics, as well as on the outcomes of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country monkeypox outbreak held on 23 June.

Outbreak at a glance

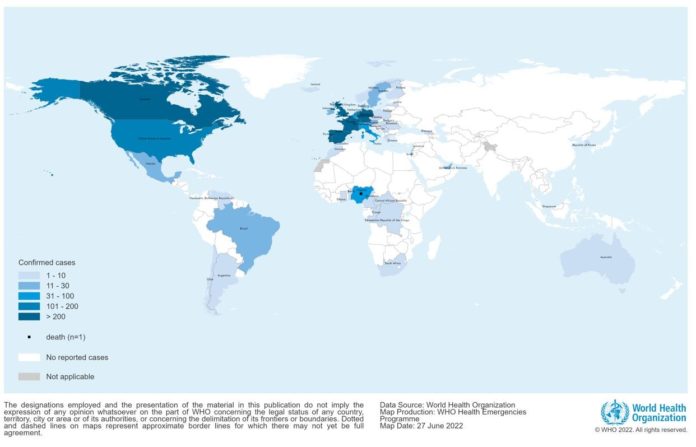

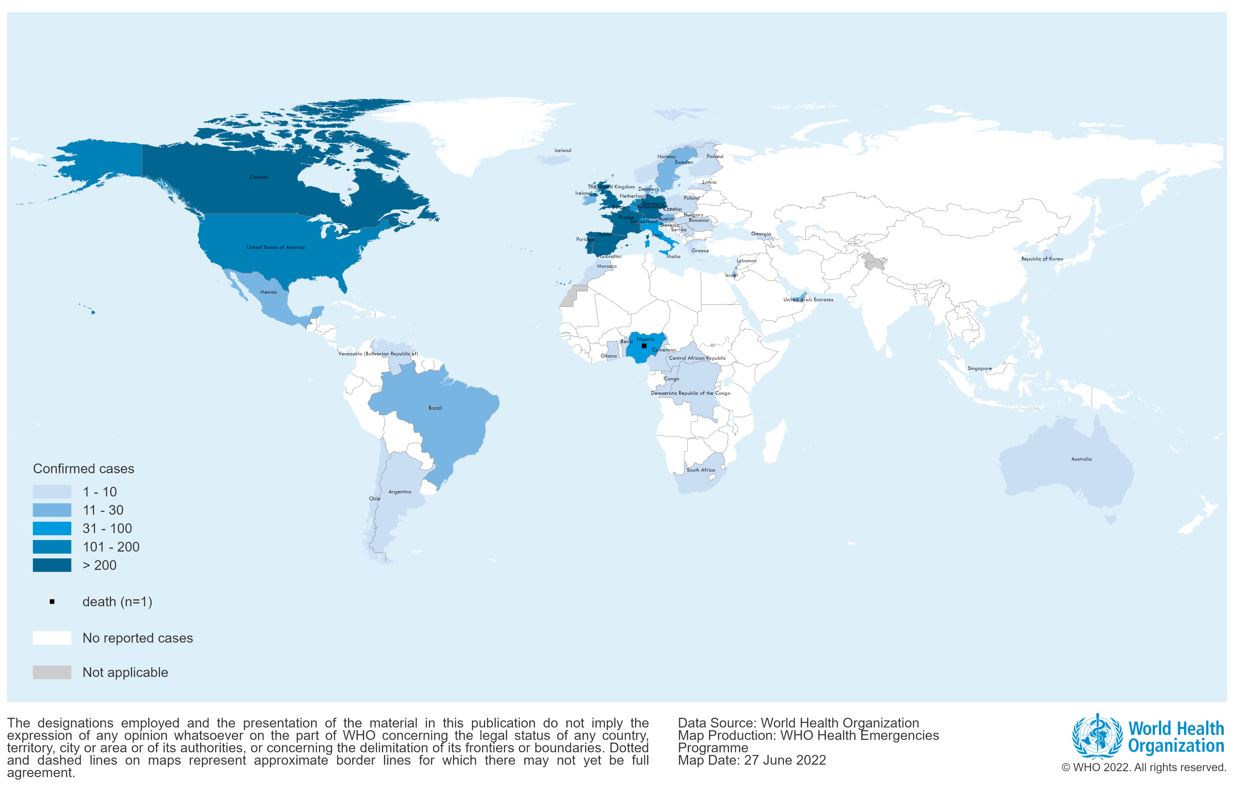

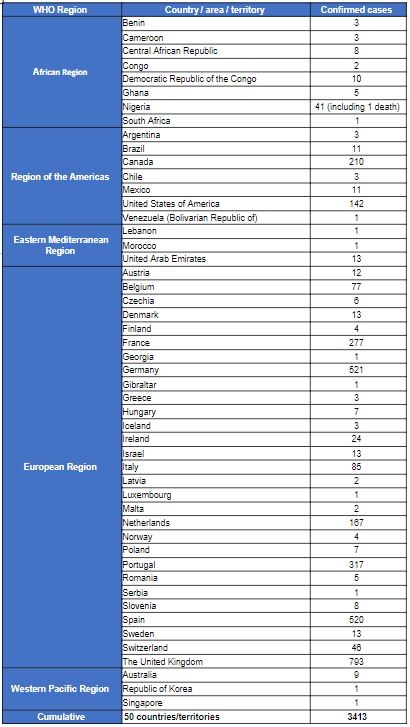

Since 1 January and as of 22 June 2022, 3413 laboratory confirmed cases and one death have been reported to WHO from 50 countries/territories in five WHO Regions.

Description of the outbreak

The majority of laboratory confirmed cases (2933/3413; 86%) were reported from the WHO European Region. Other regions reporting cases include: the African Region (73/3413, 2%), Region of the Americas (381/3413, 11%), Eastern Mediterranean Region (15/3413, <1%) and Western Pacific Region (11/3413, <1%). One death was reported in Nigeria in the second quarter of 2022.

The case count is expected to change as more information becomes available daily and data are verified under the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR 2005) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of confirmed cases of monkeypox reported to or identified by WHO from official public sources, between 1 January and 22 June 2022, 17:00 CEST, (n=3413)

Table 1. Confirmed cases of monkeypox by WHO region and country from 1 January 2022 to 22 June 2022, 17:00 CEST

The overall risk is assessed as moderate at global level considering this is the first time that cases and clusters are reported concurrently in five WHO Regions. At the regional level, the risk is considered to be high in the European Region due to its report of a geographically widespread outbreak involving several newly-affected countries, as well as a somewhat atypical clinical presentation of cases. In other WHO Regions, the risk is considered moderate with consideration for epidemiological patterns, possible risk of importation of cases and capacities to detect cases and respond to the outbreak. In newly-affected countries, this is the first time that cases have mainly, but not exclusively, been confirmed among men who have had recent sexual contact with a new or multiple male* partners.

The unexpected appearance of monkeypox and the wide geographic spread of cases indicate that the monkeypox virus might have been circulating below levels detectable by the surveillance systems and sustained human-to-human transmission might have been undetected for a period of time. Routes of monkeypox virus transmission include human-to-human via direct contact with infectious skin or mucocutaneous lesions, respiratory droplets (and possibly short-range aerosols) or indirect contact from contaminated objects or materials, also described as fomite transmission. Vertical transmission (mother-to-child) has also been documented. While it is known that close physical contact can lead to transmission, it is unclear whether sexual transmission via semen/vaginal fluids occurs, research is currently underway to understand this. In addition, the likelihood of sustained community transmission cannot be ruled out and the extent to which pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic infection may occur as the infectious period is unknown, as well as the further spread of monkeypox virus among persons with multiple sexual partners in interconnected networks and the likely role of mass gatherings.

The clinical presentation of monkeypox cases associated with this outbreak has been atypical as compared to previously documented reports: many cases in newly-affected areas are not presenting with the classically described clinical picture for monkeypox (fever, swollen lymph nodes, followed by centrifugal rash).

Atypical features described include:

- presentation of only a few or even just a single lesion

- absence of skin lesions in some cases, with anal pain and bleeding

- lesions in the genital or perineal/perianal area which do not spread further

- lesions appearing at different (asynchronous) stages of development

- the appearance of lesions before the onset of fever, malaise and other constitutional symptoms (absence of prodromal period).

The actual number of cases is likely to be underestimated, in part due to the lack of early clinical recognition of an infection previously known in only a handful of countries, and limited enhanced surveillance mechanisms in many countries for a disease previously ‘unknown’ to most health systems. Health care-associated infections cannot be ruled out (although unproven to date in the current outbreak). There is a potential for increased health impact with wider dissemination in vulnerable groups as the mortality was previously reported as higher among children and young adults, and immunocompromised individuals, including people living with uncontrolled HIV infection, are especially at risk of severe disease.

The risk is also represented by the difficulties involved in widespread lack of availability of laboratory diagnostics, antivirals and vaccines and as well as in ensuring adequate biosafety and biosecurity in diagnostic, clinical and referral laboratories everywhere that cases have occurred.

A large part of the population is vulnerable to monkeypox virus, as smallpox vaccination, which is expected to provide some protection against monkeypox has been discontinued since the 1980s. Only a relatively small number of military, frontline health professionals and laboratory workers have been vaccinated against smallpox in recent years. A third-generation vaccine MVA received authorization of use by the European Medicines Agency for smallpox. The authorization of use provided by Health Canada and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) includes an indication for the prevention of monkeypox. An antiviral agent, tecovirimat, has been approved by the European Medicines Agency, Health Canada, and the United States FDA for the treatment of smallpox. It is also approved for use in the European Union for the treatment of monkeypox.

All countries should be on the alert for signals related to patients presenting with a rash that progresses in sequential stages – macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, scabs, at the same stage of development over all affected areas of the body – that may be associated with fever, enlarged lymph nodes, back pain, and muscle aches.

In addition, during this current outbreak, many individuals are presenting with atypical symptoms which includes a localized rash that may include as little as one lesion. The appearance of lesions may be asynchronous, and persons may have primarily or exclusively peri-genital and/or peri-anal distribution associated with local, painful swollen lymph nodes. Some patients may also present with sexually transmitted infections and should be tested and treated appropriately. These individuals may present to various community and health care settings including, but not limited to, primary and secondary care, fever clinics, sexual health services, infectious disease units, obstetrics and gynaecology, emergency departments, surgical specialties and dermatology clinics.

Clinical management and Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) in health care and community settings

Caring for patients with suspected or confirmed monkeypox requires early recognition through screening protocols adapted to local settings, prompt, isolation and rapid implementation of appropriate IPC measures (standard and transmission-based precautions, including the addition of respirator use for health workers caring for patients with suspected /or monkeypox, and an emphasis on safe handling of linen and management of the environment), testing to confirm diagnosis, symptomatic management of patients with mild or uncomplicated monkeypox and monitoring for and treatment of complications and life-threatening conditions such as progression of skin lesions, secondary bacterial infection of skin lesions, ocular lesions, and rarely, severe dehydration, severe pneumonia or sepsis. Patients with less severe monkeypox who isolate at home require careful assessment of the ability to safely isolate and maintain required IPC precautions in their home to prevent transmission to other household and community members.

To enable reliable evaluations of interventions, randomized trials using CORE protocols are the preferable approach. Unless there are compelling reasons not to do so, every effort should be made to implement randomized trial designs. It is feasible to conduct placebo-controlled studies, especially in low-risk individuals. Harmonised data collection for safety and clinical outcomes using WHO’s Global Clinical Platform for Monkeypox, would represent a desirable minimum dataset in the context of an outbreak, including the current event.

Precautions (isolation and IPC measures) should remain in place until lesions have crusted, scabs have fallen off and a fresh layer of skin has formed underneath.

Laboratory testing and sample management

Any individual meeting the definition for a suspected case should be offered testing. The decision to test should be based on both clinical and epidemiological factors, linked to an assessment of the likelihood of infection. Due to the range of conditions that cause skin rashes and because clinical presentation may more often be atypical in this outbreak, it can be challenging to differentiate monkeypox solely based on the clinical presentation.

Risk communication and community engagement

Communicating monkeypox-related risks and engaging at-risk and affected communities, community leaders, civil society organizations, and health care providers, including those at sexual health clinics, on prevention, detection and care, is essential for preventing further secondary cases and effective management of the current outbreak.

For further information on risk communication for contacts, suspected and confirmed cases, and individuals who develop symptoms suggestive of monkeypox, please see the Disease Outbreak News published 17 June 2022.

Anyone caring for a person infected with monkeypox should use appropriate personal protective measures. As a precaution, WHO suggests the use of condoms consistently during sexual activity (receptive and insertive oral/anal/vaginal) for 12 weeks post-recovery to reduce the potential transmission of monkeypox for which the risk is currently not known.

Misinformation: The public is reminded that rumors and incorrect information continue to circulate on social media and other platforms regarding the current outbreak, and that it is important to check facts with credible sources such as WHO or national health authorities.

One Health

Various wild mammals have been identified as susceptible to monkeypox virus in areas that have previously reported monkeypox. These include rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, non-human primates, among others. Some species may have asymptomatic infection. Other species, such as monkeys and great apes, show skin rashes typical of those found in humans. Thus far, there is no documented evidence of domestic animals or livestock being affected by monkeypox virus. There is also no documented evidence of human-to-animal transmission of monkeypox. However, this remains a hypothetical risk. Therefore, appropriate measures should be taken, such as:

- physical distancing between people infected with monkeypox and domestic pets

- proper waste management to prevent the disease from being transmitted from infected humans to susceptible animals at home (including pets), in zoos and wildlife reserves, and to peri-domestic animals, especially rodents.

- residents and travellers to countries that have previously reported monkeypox should avoid contact with sick mammals such as rodents, marsupials, non-human primates (dead or alive) that could harbor monkeypox virus and should refrain from eating or handling wild game (bush meat).

International travel and points of entry

Based on available information at this time, WHO does not recommend that States Parties adopt any measures that restrict international traffic for either incoming or outgoing travellers.

- Any individual feeling unwell, including having a fever with rash-like illness, or who is considered a suspected or confirmed case of monkeypox by jurisdictional health authorities, should avoid undertaking non-essential travel, including international, until declared as no longer constituting a public health risk.

- Any individual who has developed a rash-like illness during travel or upon return should immediately report to a health professional, providing information about all recent travel, immunization history including whether they have received smallpox vaccine or other vaccines (e.g., measles-mumps-rubella, varicella zoster vaccine, to support making a diagnosis), and information on close contacts as per WHO interim guidance on surveillance, case investigation and contact tracing for monkeypox.

Public health officials should work with travel operators and public health counterparts in other locations to contact passengers and others who may have had contact with an infectious person while travelling. Health promotion and risk communication materials should be available at points of entry, including information on how to identify signs and symptoms consistent with monkeypox; on the precautionary measures recommended to prevent its spread; and on how to seek medical care at the place of destination when needed.

WHO urges all Member States, health authorities at all levels, clinicians, health and social sector partners, and academic, research and commercial partners to respond quickly to contain local spread and, by extension, the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. Rapid action must be taken before the virus can be allowed to establish itself as a human pathogen with efficient person-to-person transmission in areas that have previously reported monkeypox, as well as in newly affected areas.