:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/H72WBBGLPBHXPKUJTRLWQMR2II.jpg)

When an infectious disease outbreak starts, it’s like a brush fire. The flames are small and, in theory, can be contained if chains of transmission — blowing, burning debris — are snuffed out before they spark more small fires that eventually grow into a raging epidemic.

The key to it all is testing, a lesson the United States painfully learned early on with covid and is once again confronting as monkeypox spreads across the country.

Two months into this latest epidemic, the U.S. has enlisted commercial labs to increase monkeypox testing capacity to 80,000 samples a week, up from a few thousand early on. But many people who think they have the virus are running into doctors who don’t believe them or are slow to provide a test. If that gap between capacity and use persists, monkeypox could become the second new virus to become endemic in the country since 2020, despite being a much less transmissible — and thus more easily containable — virus.

“That this could happen again so quickly after SARS-CoV-2 is a choice and a failure,” said Joseph Osmundson, a molecular microbiologist at New York University. In the weeks it took the federal government to scale up testing, “we were behind and we knew it, and yet there was no urgency about scaling testing … we’ve now found thousands of cases, many of which could have likely been prevented by aggressive testing, treatment and vaccination in June.”

More than 4,600 cases have been detected in the country since early May, primarily among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM). But that is almost certainly an undercount.

In theory, monkeypox should be much easier to contain than covid. The virus spreads primarily through close physical contact and isn’t known to linger in the air like SARS-CoV-2.

But the trouble started early. When cases began surfacing, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initially insisted on PCR tests run through its centralized network of laboratories, making it difficult for people to find tests. New York, an early epicenter of the U.S. outbreak, could process only 10 tests a day by early June, and turnaround times in other major cities stretched as long as seven to 10 days, allowing the virus to spread undetected.

“This virus is likely to stick around. We are going to have to have long-term need for flexible diagnostics,” said Osmundson. Bringing in commercial labs, as the federal government did in early July, is a start, “but every spigot needs to be open.” That includes developing more kinds of tests and ensuring that providers are actually using them.

“We haven’t learned that we can’t have this wait-and-see kind of approach,” said Ranu Dhillon, an infectious disease doctor at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. As early as 2017, there were signs that monkeypox was spreading differently in Nigeria, where the virus is endemic. “From day one when there was a concern of an emerging pandemic with monkeypox spreading around the globe, we should have made a lot of the steps that are only now coming online,” Dhillon said.

ADVERTISEMENT

All our testing eggs are in one basket

Right now, there’s basically only one way to get tested for monkeypox.

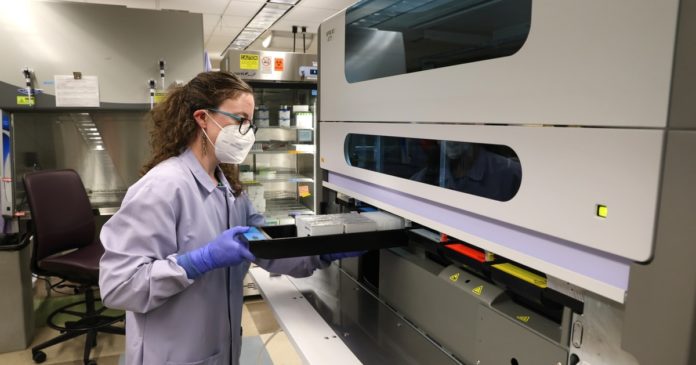

The PCR test, developed by the CDC and approved by the Food and Drug Administration, detects any DNA from orthopoxviruses, a family that includes monkeypox but also non-circulating viruses like smallpox. Providers swab external rashes or lesions to pick up that DNA and then send those swabs to one of the 66 labs in the CDC’s Laboratory Response Network, or commercial labs such as Labcorp or Quest Diagnostics, for testing.

While external lesions are a hallmark symptom of monkeypox, not everyone with the virus gets them, and if they do, they can often appear after people feel sick or get extremely painful internal lesions. And primary care providers may not be reading the latest reports on how the virus is presenting, which can influence whether or not they authorize a test.

“One of my friends, whose story was reported widely, could not get testing because he first showed up with only internal lesions,” said Keletso Makofane, a public health researcher at Harvard University. His sexual history and other symptoms were consistent with monkeypox, Makofane said, “but he still couldn’t get tested and wasn’t initially treated as a monkeypox.”

Some other anecdotal reports have surfaced of people who have had trouble getting tested because they are not men who have sex with men, the group in which most initial cases occurred in the U.S.

ADVERTISEMENT

Together, these stories suggest that many potentially infected people aren’t being tested soon enough to stop transmission and treat those suffering.

“We need to be moving full steam ahead on developing assays using other biological samples, like saliva, oral swabs or blood,” Osmundson said. “Those are all published to contain monkeypox DNA and so would be a good clinical sample for a PCR test.”

Reliance on a single test is worrisome for other reasons too, Osmundson said. In the early days of the covid pandemic, the only available test was developed and distributed by the CDC. Many of the CDC tests contained a faulty ingredient that left them unusable. “What happens if there are reagent shortages or contamination with this one test?” asked Osmundson. “What happens is nationwide testing goes to zero immediately, and we’ll be in the dark for days to weeks.”

Let a thousand tests bloom

The U.S. needs to diversify testing, with nongovernmental labs developing different kinds of tests, Osmundson said. So-called laboratory developed tests are designed by private labs and could make the U.S. testing capacity more expansive and resilient.

To develop these tests, labs need clinical samples from confirmed monkeypox patients, something they’re having trouble accessing, Osmundson said. “God knows we have enough patient samples; the CDC received all of them. Why aren’t they partnering with NIH and approved labs to disseminate the samples such that labs can develop tests immediately and offer those tests to patients now?” Osmundson asked. “This is completely possible under current law.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The most robust laboratory-based testing system can’t reach everyone, as the covid-19 pandemic has shown. “Even with the increase in testing capacity, all of that is through the health system, and many people aren’t connected to that health system,” said Dhillon.

To get tests to those people, “we need to invest in something more decentralized and agile,” Dhillon said. “An important piece of the solution is advancing some kind of rapid, point-of-care diagnostic test, akin to what we do with covid.”

Such a test would allow people to self-test, which is especially important when some may feel stigmatized when going to their doctor. It would also empower community organizations to bring tests to groups most at risk. “That’s a crucial missing piece. That would give us the scale, allow people to test without stigma and get fast identification of people who are infected,” said Dhillon.

Provider education

Tests do good only if doctors and other providers know to use them. Right now, monkeypox is still on too few radars, leaving many cases undiagnosed or treated.

“A lot of clinicians have not been sufficiently updated on the epidemic,” Dhillon said. Monkeypox symptoms can resemble diseases like syphilis, herpes, even insect bites, and many clinicians spend time ruling out all other options before considering monkeypox, if they do at all.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Just anecdotally, in the hospitals I work in, many people’s threshold for testing is probably higher than it should be,” he said. “We need to make it more acceptable so that you’re routinely testing people even if they have minorly suspicious symptoms or exposures; that’s how you’re going to uncover where that hidden transmission is happening.”

In some areas, people who think they have monkeypox are simply getting turned away. “Primary care docs, ER rooms, dermatologists, they’re all turning patients away because they don’t have experience with this and sending them to sexual health clinics,” said David Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors.

Sexual health clinics are trusted community providers for many gay and bisexual men, Harvey said, but are ill-equipped to handle a huge influx of patients. “These clinics operate on shoestring budgets and are already dealing with an out-of-control STI epidemic,” he said. Many don’t have the money to pay for testing at commercial labs or the capacity to bill insurance, Harvey said, “which means that most still rely on the public health lab system, which is frayed.”

The federal government has urged providers to be on alert for monkeypox, and certain state and city officials have implemented more targeted awareness programs for LGBTQ+ communities. “But if we use the HIV experience as an indication, I think we will have to develop healthcare provider training programs,” Makofane said. Organizations like Fenway Health, which gives providers training in care focused on LGBTQ+ patients, will be especially important, he said. “We really want to make sure that there’s a large cadre of healthcare providers, outside of specialty services, who can watch out for monkeypox.”

Gaps in data

Robust testing is key for providing care to individuals who contract monkeypox, but it’s also needed to understand the scope of the epidemic nationally. Right now, the U.S. is largely flying blind.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Neither the administration nor the states have made any data available on how many tests are actually being run, and on whom,” said Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University. Demographic data, like age, race, sexual orientation or sexual behavior, isn’t being routinely collected or shared, she said: “That makes it really difficult to answer key questions,” like how many tests are coming back positive and who is being infected.

“We know from data the United Kingdom publishes that test positivity in women and children is very low, which gives us confidence that it’s not circulating outside of MSM, but we don’t have similar metrics in the U.S.,” Rivers said. Without that basic data, public health officials can’t keep up with the spread.

Normally, the CDC does not have direct authority to require states or private labs to share data, and as a result only has demographic information for about half of all cases. The situation was similar with covid until it was declared a public health emergency, allowing the agency to compel states to share. The administration is reportedly weighing declaring monkeypox a public health emergency but is also planning to call the disease a “nationally notifiable condition” in August, Politico reported, which would compel more data-sharing.

“It’s really important to clearly state our objective, which I think should be containment, and then set metrics and targets for how we track progress toward that goal,” Rivers said. “If those metrics aren’t improving, then we can adapt our response.” But without adequate testing and data-sharing, monkeypox could permanently establish itself in the U.S. without us noticing. We may have already missed it.

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.