Pathogens have a way of shining a light on the darker facets of society. SARS-CoV-2 has certainly done that with Covid-19, and the monkeypox virus is doing it again.

Pathogens don’t discriminate like humans do — they have no innate capability of discerning race, sexual orientation, religion, or nationality. This isn’t to say their effects are equal across different populations. Pathogens capitalize on individual vulnerabilities, exposures, and behaviors. They also hijack structural inequities embedded within societies.

Monkeypox isn’t new. The first known human case occurred more than 50 years ago in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Since then, it has been primarily associated with a number of countries in west and central Africa, although there was a small outbreak in the United States in 2003.

advertisement

In May, cases simultaneously popped up in a number of countries for the first time, including the United Kingdom, Spain, and Canada. As I write this, at least 700 cases have been confirmed worldwide. The majority of early cases occurred among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, and European authorities are investigating cases associated with a men’s sauna and gay festivals.

Practically on cue, monkeypox has been portrayed in stigmatizing ways. Emphasis on same-sex sexual acts has been flagrant at times. So far, it isn’t known if the virus is transmitted through semen. Even if monkeypox is not transmitted through sexual activity, it may have still been able to take hold in sexual and social networks in which people have close skin-to-skin contact. Language conflating monkeypox and sexuality, however, stigmatizes the community of men who have sex with men, and carries the risk of “driving people away from health services, impeding efforts to identify cases, and encouraging ineffective, punitive measures,” as Matthew Kavanagh, UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director, recently stated.

advertisement

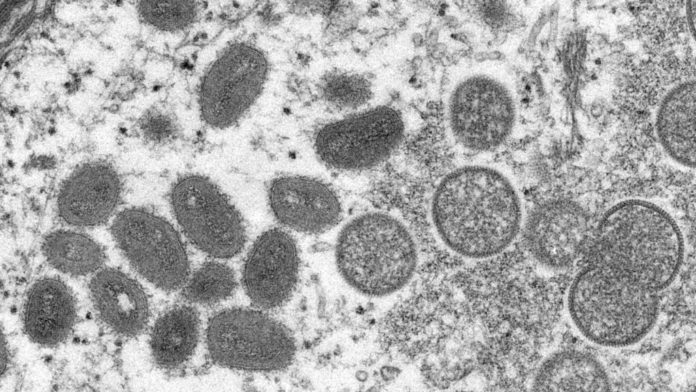

There has also been a racial dimension to the stigma. Initial Western reporting on the monkeypox outbreak extensively used stock images of dark-skinned people with visible rashes on their body, something the Foreign Press Association, Africa has decried. This mischaracterization stigmatizes Africans as disease sufferers in an outbreak that is primarily occurring among Europeans and North Americans, and in the process creates misinformation about who is at risk in the current outbreak.

Quite quickly, the monkeypox outbreak has also reflected the current state of global health inequity, which privileges Western voices and lives. North American and European clinicians could learn from their African colleagues, who have the most direct knowledge and experience with diagnosing and treating monkeypox. African researchers have produced countless relevant journal articles that may shape understanding of the current outbreak. Systemic barriers to academic publishing mean, however, that many voices in countries where monkeypox is endemic were never able to join the discourse. Gaps in current knowledge of monkeypox reflect a long history of deprioritizing African researchers and research into diseases of the Global South.

It is ironic — but utterly predictable — that monkeypox will become a global priority now that people in the Global North are getting the disease. High-income countries have access to post-exposure prophylaxis with vaccination or immunoglobulin. After the first U.S. case of monkeypox was reported, the Biden administration purchased $119 million worth of smallpox vaccine, which is licensed for use against monkeypox. European countries are considering stockpiling antivirals. These targeted therapeutics are not widely available, however, and if the Covid-19 pandemic provides any insight, there will be no rush to distribute them to African countries where monkeypox is endemic.

The world seems to be repeating a historical script of perpetuating stigma and structural inequity that has plagued responses to other outbreaks. HIV, for example, is recurrently portrayed as a disease of gay men and Africans, and early depictions of Covid-19 focused on Asians. Since the Ebola epidemic of 2013-2016, this disease has receded as an important international priority, despite the fact that outbreaks continue to appear, as recently as two months ago in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Finally, at a time when the Global North is trying to “move on” from the Covid-19 pandemic, a profoundly imbalanced vaccine rollout has left just 17% of Africans fully vaccinated, compared to as many as 75% on other continents.

As a gay man and a global health physician, I know there are ways to begin flipping this script. In the early stages of any outbreak, it’s essential to avoid simplistic headlines and unrepresentative images, taking care to communicate the limits of knowledge. Clear, targeted public health information for communities of men who have sex with men is still necessary, however, especially as we enter Pride season. This can be accomplished without blending sexuality and disease, and queer communities can lead the way in tailoring and amplifying health messaging through social media and at community festivals this summer. We have a long history of rallying around public health emergencies that affect our communities.

Monkeypox also represents an opportunity to interrogate some larger global health paradigms, like whose voices and lives are prioritized, and for whom resources are mobilized?

The threat of pathogens, new or old, is very real for everyone on Earth, but the global health security agenda still feels like America and Europe First. Collective resource allocation, either regionally or globally, would provide better security for all of us. This applies not only to monkeypox, but also to the next disease that spills over from animals to humans. Until the global health community actually commits to cooperative action, it is making a deliberate policy choice to neglect diseases until they arrive in the Global North.

Pathogens are here to stay, but the key drivers of outbreaks — who is perceived to be infected, who actually is infected, and who gets treated — are determined by human responses to pathogens. With monkeypox, and other outbreaks that are sure to follow, we must choose to learn from our mistakes.

Vinay Kampalath is a pediatric emergency medicine physician, a global health specialist, and an associate fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.