:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/BBCAYJGGUNAFPEFVV6RCY5NUC4.jpg)

The rare global monkeypox outbreak is just weeks old, but the early focus on cases among gay and bisexual men risks blinding the world to the risks posed by the virus — and increasing stigma.

Much of the coverage of the outbreak, especially on social media, has framed monkeypox as affecting only men who have sex with men — a false narrative that to many public health experts echoes the early days of the AIDS crisis. They’re worried that the emphasis on cases among gay and bisexual men could lead many people to assume they are not at risk and ultimately undermine efforts to contain the outbreak.

Since the outbreak, headlines like “Gay Community Most Vulnerable to Monkeypox Threat,” “CDC warns LGBTQ community at higher risk to get monkeypox,” and “Monkeypox likely spread by sex at two raves in Europe, expert says,” have framed monkeypox as a “gay disease” spread primarily through sex. In truth, it spreads by close contact (sex included). And previous outbreaks of the disease, which was first identified in humans a half-century ago, have affected all types of people.

So far, most identified cases have been in gay or bisexual men. But experts suspect this pattern likely stemmed from a chance event, or events, that then reverberated through close social networks.

ADVERTISEMENT

“This is a disease that can affect anyone, but currently seems to be affecting gay men,” said Keletso Makofane, a public health researcher at Harvard University. “We need to talk about monkeypox in a way that can help us respond to it without causing further harm in a community that is already marginalized,” he said. “We have to be able to attend to those with the highest risk and burden now, but we know that singling out gay men elicits homophobic responses.”

If monkeypox becomes a “gay disease” in the public’s mind, we risk repeating many of the same mistakes made during the beginning of the AIDS crisis 40 years ago that led to needless suffering and death, Makofane said. Because of that framing and stigma, many straight people assumed they couldn’t get HIV/AIDS, and many gay people were ostracized and denied care.

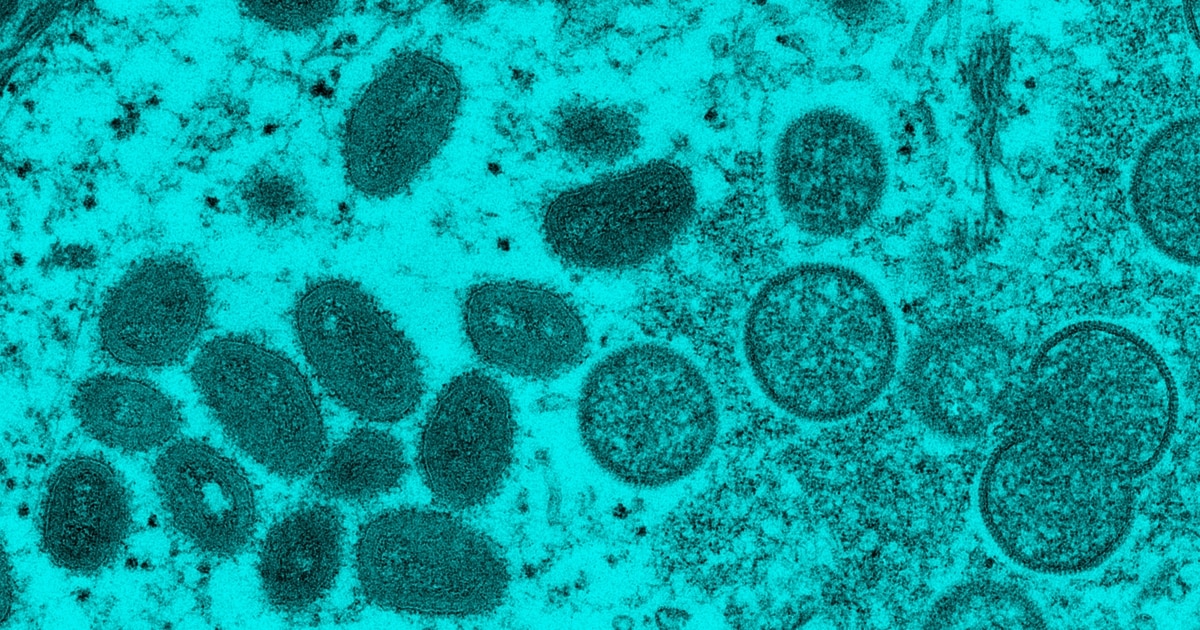

Monkeypox was discovered in a monkey in 1958. The first human case was detected in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970. Since then, two major strains of the virus have become endemic to several African countries, meaning that it is continuously present.

Most of the time, humans catch the virus from close contact with rodents or other animals. Human-to-human transmission has been relatively rare, but can happen via close contact with lesions, bodily fluids, respiratory droplets and contaminated materials like bed sheets, according to the World Health Organization. Monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted disease like HIV, but sex certainly counts as close contact and can facilitate spread.

A cautionary tale

In early May, public health officials became aware that monkeypox was spreading in a way not seen before. Cases seemingly unconnected to travel from Africa began surfacing across Europe. Over the past several weeks, clinics have identified more than 230 confirmed or suspected cases in 18 non-African countries, mostly among men who have sex with men. The outbreak has centered in Europe but has also reached the United States and Australia. All known cases stem from the less virulent strain, endemic to Western Africa, which can cause fever, headache, fatigue and lesions concentrated around the genitals. Most people recover within two to four weeks on their own.

ADVERTISEMENT

Why the monkeypox virus is suddenly spreading so rapidly, mostly among gay and bisexual men, is still unclear. But it’s almost certainly not because this group of people is inherently at higher risk.

“We don’t know for sure whether there are other populations who have it,” said David Heymann, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and an adviser to WHO.

“I would think there was some random event when somebody who became infected had some genital lesions, and then [the virus] is being perpetuated by close physical contact,” he said. “Transmission is amplifying in a population that’s allowing it to spread more rapidly than it would normally.”

Some early news reports have linked outbreaks to gay saunas, Pride festivals and raves across Europe. “These large gatherings likely facilitated close contacts and transmission events leading to clusters within shared social networks,” said Boghuma Kabisen Titanji, an infectious disease physician at Emory University. “Traditionally, men who have sex with men are known to be very proactive about their health,” she said. Their current overrepresentation in cases might simply be a reflection of this extra attentiveness, coupled with common social networks, activities and exposures, she said.

“This does not mean that similar conditions will not facilitate transmission in heterosexual men, women and children,” Titanji added. “Everyone should be aware that there is an outbreak and the virus can spread to anyone who is vulnerable given the right conditions.”

Framing the disease as only affecting gay and bisexual men may obscure the potential risks to the broader population and stigmatizing those currently most impacted. Such a path risks repeating the messaging failures of the early days of the AIDS crisis.

In the early 1980s, before the term AIDS was introduced, the disease was referred to as GRID, or “gay-related immune deficiency,” despite evidence that women and heterosexual men were also affected. That framing led to “incredible stigma targeting [gay and bisexual men] who were ostracized, blamed and shamed for being ill,” Titanji said. “It delayed meaningful action to fully address the epidemic and drove many who contracted the infection underground.”

Multiplying harm

Stigmatization adds an extra layer of harm on those already suffering and makes controlling a public health crisis that much harder. HIV-related stigma increases risk of depression and anxiety in the stigmatized, and may actually increase risky behavior, according to a 2011 study. People who feel stigmatized may be less likely to report symptoms for fear of backlash, frustrating efforts to contact trace outbreaks and deliver care.

By framing the monkeypox outbreak as a gay disease, “we shoot ourselves in the foot overall and fail to respond in a way that defends the right to health of gay men,” said Makofane. Public health officials must walk a fine line of alerting those at most risk now while avoiding stigmatization and clearly communicating that the situation could change, Makofane said. “Just because we have this particular picture now doesn’t mean that’s the picture that’s going to stay.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is already trying to walk that line. At a Tuesday press conference, officials announced efforts of targeted communication to gay communities to raise awareness about monkeypox risk and how to seek care ahead of Pride Month, which kicks off over the Memorial Day holiday weekend.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Some groups may have a greater chance of exposure right now, but by no means is the current risk of exposure to monkeypox exclusively to the gay and bisexual communities in the U.S.,” said John Brooks, chief medical officer for the CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention.

Going forward, Makofane hopes public health leaders communicate clearly why we might be seeing current groups being impacted more, while emphasizing that epidemics often change. “Just because we have this particular picture now, that doesn’t mean it’s the picture that’s going to stay,” he said. “We can’t make the mistake of conflating the current state of the epidemic with notions of susceptibility and resistance to that pathogen.”

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.