Japan has only seen a handful of monkeypox cases so far, with the government making concerted efforts with medical institutions and activists to contain the disease when it is detected domestically.

But with the risk of more cases appearing, and the global outbreak currently mostly affecting men who have sex with men, some question how well Japan can tread the line between preventing stigma and adequately informing the population of the reality of the disease.

Though monkeypox is usually confined to Central and West Africa, where it is endemic, the current outbreak, which began in May, has been concentrated in Europe and North America. According to the World Health Organization, as of Aug 23, over 41,000 people worldwide have been infected so far this year.

The WHO has stressed the disease is not only transmitted through sex and that anybody, regardless of sexual orientation, can be infected.

Still, “around 98 percent of patients are known to be gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men,” said Tomoya Saito, who heads the Center for Emergency Preparedness and Response at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases.

All four confirmed patients reported in Japan thus far are male. But a lack of in-depth explanation of the disease or how it is transmitted has allowed ungrounded assumptions and prejudice to spread online.

On a YouTube video about an overseas monkeypox patient published by a major broadcaster, one comment erroneously states, “I’m relieved (I can’t get the disease), because it’s only limited to gays.”

After the WHO recently announced it was accepting suggestions for a new name for monkeypox to avoid negative associations with the animal it is named after, numerous Twitter posts in Japanese appeared proposing names incorporating homophobic slurs.

Through the institute, Japan’s current procedure to tackle the disease is to “test and diagnose individuals as soon as possible, ask close contacts to take preventive measures, and vaccinate them if necessary so that it does not spread any further,” said Saito in a recent interview with Kyodo News.

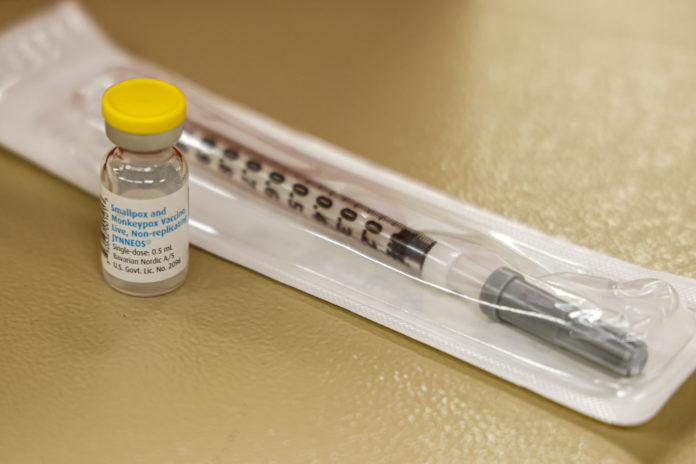

But while the health ministry has approved using a domestically manufactured smallpox vaccine known to be effective against monkeypox, jabs have so far been limited to close contacts.

This contrasts with the larger rollouts for vulnerable groups in countries like the United States and Britain, where cases have ballooned.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had reported more than 16,600 monkeypox cases as of Aug. 24, currently the highest number in the world. Britain, meanwhile, reported 3,000 cases as of Aug. 22, according to its government website.

Monkeypox symptoms include fever, intense headaches and painful skin lesions. Exposure to the bodily fluids of an infected person, or prolonged close contact with a patient’s lesions, including through sex, kissing, or hugging, is thought to transmit the virus.

“Originally coming from animals, it is thought that by chance a male patient who has sex with men was infected and that lesions appeared around their genitals,” Saito said, adding that experts believe the virus can spread more easily via sexual contact.

“Lesions in MSM (men who have sex with men) patients have been detected around the genitals, anus and mouth,” concurs Shigeru Morikawa, professor of microbiology at the Okayama University of Science’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. In contrast, in Africa, lesions “have mostly been observed on the face and hands,” he adds.

Monkeypox is not believed to spread as easily as COVID-19, whose infectiousness led Japan to impose controversial border restrictions on overseas arrivals.

But Saito has said that cases could go up “as restrictions are gradually relaxed and the number of people coming and going increases,” noting that the number of travelers heading from Japan to regions where monkeypox has been reported is on the rise.

With Japan’s community of MSM appearing to be most at risk of the virus, Kota Iwahashi, head of the non-profit organization Akta that raises awareness of HIV, wonders how such a conservative country can handle monkeypox when conversations on LGBTQ issues and sexual health are still largely taboo.

Originally formed in 2003 as part of a joint project between NPOs and the health ministry and based in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ni-chome district, famed for its large cluster of gay bars, Akta has long engaged in community-based activities to educate people on HIV testing and prevention.

It now also plays a key role in reaching out to Tokyo’s MSM population about monkeypox while also being is involved in discussions with the government and institute of infectious diseases on how to address the virus. Additionally, it shares information via Youtube videos and its website, including links to health ministry sites with some information in English.

Akta also provides direct feedback to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare on the community’s thoughts and fears. “We’ve gotten a huge number of inquiries,” Iwahashi said. “Many in the community are afraid of being outed as gay at school or work if they get the disease.”

Iwahashi, 38, said that he was too young to experience the AIDS crisis when it arrived in Japan. “But I know that at the time, many only saw it as a ‘gay disease’ that affected a minority. I think exactly the same is happening now with monkeypox.”

Iwahashi said he does not expect Japanese mass media to go into detail when talking about monkeypox. To get the correct information out to vulnerable communities, Akta and other similar organizations must fill in the knowledge gaps, he said.

© KYODO