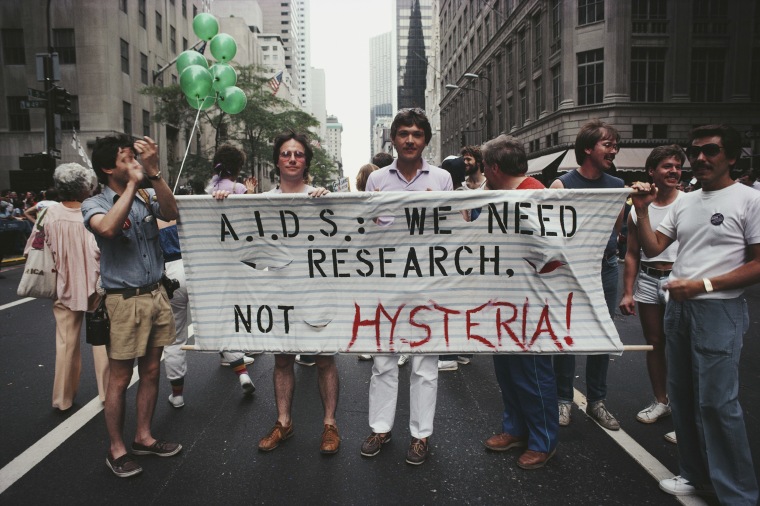

In the early days of the HIV epidemic, in the 1980s, governments around the world mailed public health information to households featuring images of tombstones and death. For even the least-informed citizens, the message was clear: There was no cure for this new disease spreading globally through sex and other pathways.

“These early communications, amplified by an often hostile mainstream media, created significant fear that fed stigma and discrimination for decades,” Andy Seale, an adviser to the World Health Organization’s global HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections programs, told TODAY via email.

“Some might even argue that the harmful legacy of those early information campaigns continues to this day.”

Related: As monkeypox outbreak spreads, these pictures can help you identify symptoms

It’s a legacy that public health experts are trying to avoid with the newest global outbreak driving headlines and information campaigns — monkeypox.

As of Friday, more than 2,500 cases have been confirmed in 37 countries outside West and Central Africa, where the virus is endemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the United States, 20 states and the District of Columbia have recorded 113 total cases, also per the CDC.

“Early data suggest that gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men make up a high number of cases,” the CDC notes on its landing page for the monkeypox outbreak. Back in 1981, when the CDC first used the term “AIDS,” the agency observed that roughly “75% of AIDS cases occurred among homosexual or bisexual males.”

Last month, the CDC sounded the alarm about the monkeypox outbreak to gay and bisexual men, calling attention to the delicate, public-health dance of making sure an at-risk, marginalized group knows how to protect itself without sending the message that its members are the only people being infected or are responsible for the outbreak.

“It’s really important that we don’t associate (monkeypox) with one population,” Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, CDC’s director for HIV/AIDS prevention, told TODAY. “It creates stigma and misinformation, and everyone needs to get the right information.”

Daskalakis, who’s credited with decreasing HIV rates to a historic low, stressed the importance of learning from the mistakes of the early years of the HIV epidemic.

“When comparing monkeypox to the HIV crisis, this is something new going on, and there’s a lot that’s still unknown. And that’s where the comparisons should end,” he said. “The virus doesn’t discriminate. Lead with science, not stigma. Infections don’t understand identities.”

Seale agreed that public health authorities are still learning from the HIV outbreak and applying those lessons today.

“When we develop messages for a community that has experienced notable rates of infection, it is important that messages are balanced both for that particular community and also others from outside that community — viruses, including HIV and monkeypox, do not care about someone’s sexual orientation or sexual history,” he explained.

“We need to be mindful that viruses can move into different social and sexual networks, and any over-association with a particular group could both halt individuals from seeking health advice and possibly act as a barrier to health professionals presented with symptoms in what they might consider to be someone with little or no risk.”

The perspectives of gay individuals are also driving messaging this time around, thanks to Daskalakis and WHO advisory groups featuring LGBTQ experts from around the world.

“The collective expertise of public health and community representatives is central to this work,” Seale said. “Should the outbreak move to other groups then the same principal of community engagement will apply.”

While public health experts continue to gather information about the outbreak, Daskalakis reminds the public to take precautions, but not to panic.

“This is about knowledge, not anxiety,” he said. “Just like we’ve trained ourselves from dealing with the coronavirus pandemic, if you’re sick, stay home. Now that includes a rash. Don’t panic and see a doctor.”

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus, a member of the same family of viruses as smallpox. The smallpox vaccine will play a key role in controlling this outbreak. Historically, monkeypox symptoms have started with fever, headache and muscle aches followed by its telltale rash, which usually starts on the face or in the mouth. But in this outbreak, the rash has often started on the genitals or around the anus without evolving to the face or extremities and many people don’t experience fever or aches at all.

This outbreak is the first time this many monkeypox cases have occurred at the same time in disparate countries around the world, WHO said in a recent report. Most transmission in the current outbreak has been linked to sexual conduct. The CDC recently issued guidance for safe sex as monkeypox continues to spread, including reducing skin-to-skin contact, avoiding kissing and washing hands, linens and any accessories used after sex.