As early as the 1830s, the black abolitionist and social reformer Frederick Douglas observed white men darkening their faces with burnt cork for satirizing and ridiculing Black people in public performances. One of those performers, Thomas D. Rice, later saw a former Black slave dancing a jig and singing a plantation song called “Jump Jim Crow.” By creating a caricature of this traditional slave tune and placing it in “blackface” productions, he further demeaned this race in what became known as “minstrel shows.” Impresarios turned them into three-part plays with jokes, songs, and skits, and from about 1850 to the 1930s minstrel shows remained the most popular entertainment across the United States, including Quincy. Remnants of this racist theater continued until the early 1960s.

Minstrel shows began in Quincy just before the Civil War and by the 1870s received top billing at the Opera House and Empire Theater, the town’s leading venues. In November 1877, the oldest minstrel organization in the country, Duprez & Benedict, came to Quincy and played to sold-out audiences. While white men (and later women) in blackface comprised nearly all of the major touring shows, some Black companies also engaged in minstrel entertainment, attempting to rise above the lot of almost all Black people in the country. Sprague & Blodget’s Original Georgia Minstrels and Mahara’s Minstrels (billed as “20 colored performers”) played to enthusiastic audiences at Quincy’s Opera House.

While both Black and white audiences attended minstrel shows, racial segregation remained rampant in Quincy. When the Mahara’s Minstrels appeared at the Casino a notice in the Nov. 8, 1893, Quincy Daily Whig stated: “The management desires to correct the misunderstanding that there is any intermingling of the blacks and whites. It is not so. Perfect arrangements have been made for the colored people in their own section of the house.”

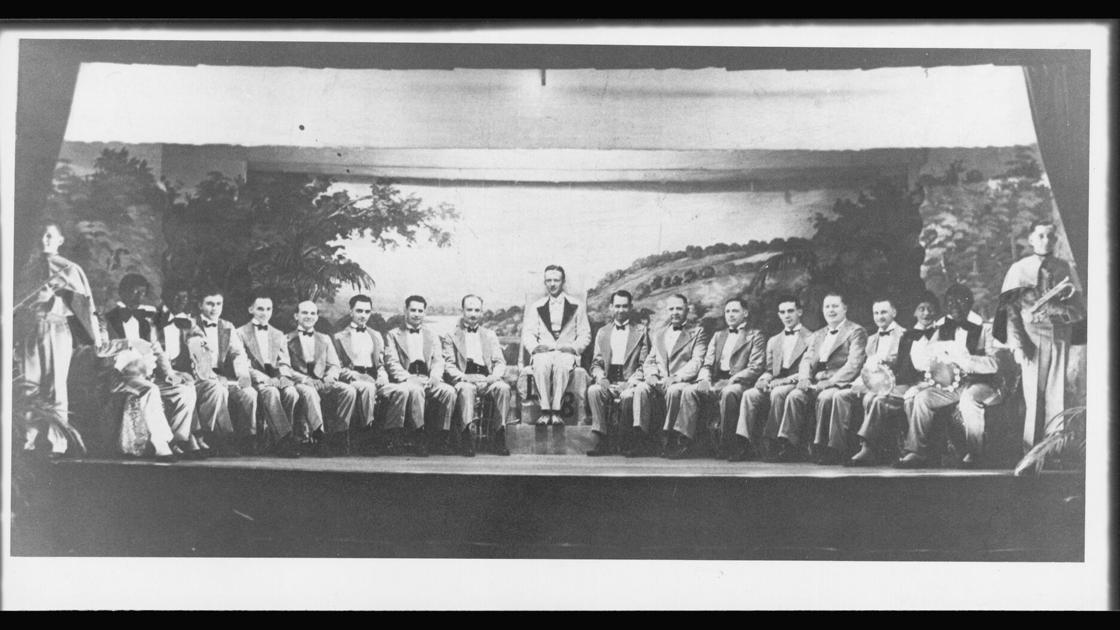

By the beginning of the 20th century, not only did Quincy theaters present minstrel shows but service organizations also promoted them. To raise money for charitable causes, the Elks, Moose, Triple Oaks, Knights of Columbus, Eagles, Masons and Turner Hall regularly held productions. The Moose even formed its own dramatic minstrel club. A Knights of Columbus performance billed itself as the “Three KCs”: the Knights of Columbus’ initial show, Kansas City, the hometown of the touring company, and the “Kute Comics” performing in the show. An advertisement noted that a KC member and former Quincy resident, Charles Jochem, composed one of the songs.

Many local churches also held minstrel shows. The Salem Minstrels, comprised of members of the church’s Men’s League, staged many shows in Salem Hall, complete with orchestra and banquet before the performance. St. John’s Catholic Church announced that their 1916 show netted a profit of $230, an almost 100% increase from the previous year. St. Francis Solanus Church held large annual minstrel shows for more than 20 years and had to reschedule the date one year because it conflicted with a Holy Name Society meeting.

Public schools also hosted shows performed mostly by students and their parents. Among many productions in the early 1900s, Jefferson School mothers acted as the “Dark Town Ladies Minstrel” to help purchase a piano. Jackson School’s eighth grade class staged a show for the benefit of the baseball team and the Centennial Debating Club of Quincy High School performed an original minstrel show composed by local resident John Guill.

During World War I, several organizations sponsored minstrels to inspire patriotism and national solidarity for the American cause. Since its inception, performances of minstrelsy usually ended with a flag-waving grand finale of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” After the war ended, Fifer Minstrels of Quincy’s Soldiers and Sailors Home organized a city-wide parade for returning servicemen followed by a show in the Armory.

Black soldiers, though, who had fought in the war expected better treatment and respect after returning to the States. Even before the war began, the Empire Theater issued a disclaimer in the March 7, 1912, Quincy Daily Herald about racial insensitivity. “All elements of coarseness have been studiously avoided and the entertainment could pass muster at the hands of Sunday School censors.”

An editorial in the Nov. 10, 1917, Quincy Daily Whig, though, tried to justify this profitable genre during a time of widespread racial segregation. “The modern minstrel evolved from the colored race. The Negro himself makes the best minstrel man if he can be restrained from being self-conscious…any person is sure of a good laugh if they can but be around a group of Negros 30 minutes.”

Minstrelsy began declining during the 1920s as other forms of entertainment like vaudeville and movies emerged. Vestiges of this racist theater, though, continued in these newer venues. The movie “Birth of a Nation,” which cast blackface actors in demeaning portrayals of Black people, played to overflow audiences in Quincy and across the country, and kindled a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. During the Great Depression, Quincy neighborhoods sometimes staged informal shows performed by residents to help those hurting during these hard times.

As the aggression in Europe that would lead to World War II escalated, some local minstrelsy replaced blackface with performances that denigrated Japanese and Germans — Allied enemies during the war. The Men’s Club of Emerson School performed “Sultan Minstrel,” billed as a “gay minstrel with an Oriental setting” and the Empire Theater staged “Wang” starring the “Kamekichi Japs.”

While minstrel shows sporadically continued in Quincy until the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s, the word “minstrel” itself began appearing more in newspaper crossword puzzles as a clue for “troubadour” than denoting a form of entertainment. A question-and-answer column in the Dec. 18, 1961, Quincy Herald-Whig asked, “What is the origin of ‘Jim Crow?’” The term that now meant separate and unequal treatment of Black people evoked in this query its roots in the song-and-dance jig once done by slaves on plantations that distorted the country’s racial perception by creating a mocking and demeaning image of black people.

“Amusements.” Quincy Daily Whig, Nov. 8, 1893, 3.

“Attractions at the Empire.” Quincy Daily Herald, March 7, 1912, 9.

“Minstrel Show at Empire.” Quincy Daily Whig, Nov. 10, 1917, 4.

“Minstrels Are Great.” Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 9, 1915, 9.

“Minstrels Organize New Dramatic Club.” Quincy Daily Whig, April 27, 1917, 9.

“Oriental Setting For Gay Minstrel By Emerson Men.” Quincy Herald-Whig, May 3, 1933, 12.

“Question and Answer.” Quincy Herald-Whig, Dec. 18, 1961, 14.

Riggs, Marlon. Ethnic Notions: African American Stereotypes and Prejudice. San Francisco: California Newsreel, 1987, film.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.