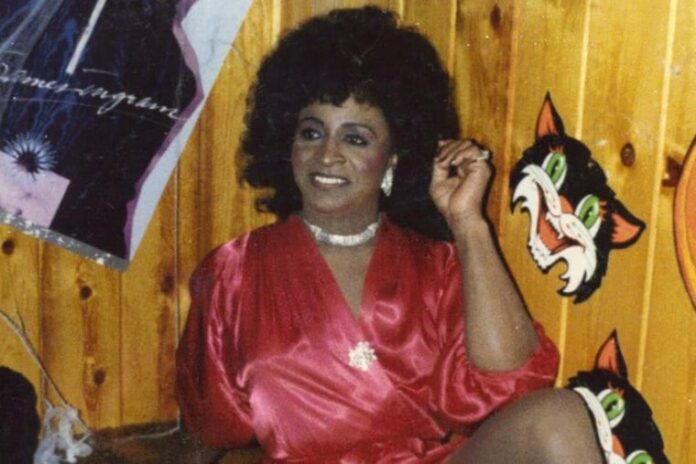

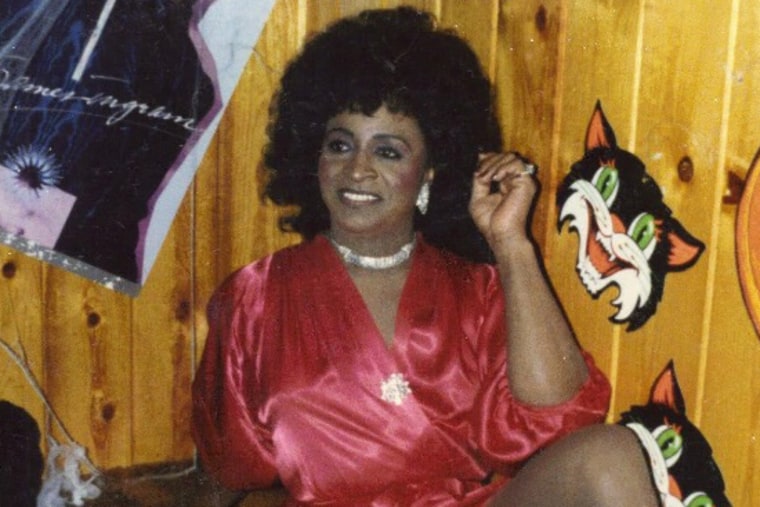

In the early evening hours of Aug. 5, 1961, Josie Carter was sitting at the bar in the Black Nite, a gay tavern in Milwaukee, doing her makeup in her bathrobe.

Later that evening, she would lead bar patrons as they fought back against a group of Navy service members in what some historians believe could be the first recorded LGBTQ uprising in the country.

The event became known as the Black Nite brawl, and though the bar itself is no longer standing, the Milwaukee County Landmarks Committee is expected to designate the site a historic landmark.

Historian Michail Takach, who nominated the bar for landmark recognition, said the Black Nite brawl was almost lost to history, in part because Carter was so modest and humble that she didn’t want herself or the event commemorated while she was alive. She died in 2014 at the age of 73.

“This is a remarkable story for a trans woman of color to have changed history the way she did, especially because she exhibited throughout her life so much Midwestern modesty that no one would have ever guessed that she really did this,” said Takach, who is the co-founder of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project and interviewed Carter about the event. “It does show that when people take a stand regardless of the risks and consequences, they can change history.”

On Oct. 5, the Milwaukee County Landmarks Committee held a public hearing to discuss four landmark nominations, including the site of the Black Nite. Though the committee won’t make an official decision until next month, the chairman told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that “it’s going to happen.”

During the hearing, author Diane Buck said the unrest at the Black Nite began when four servicemen showed up at the bar and refused to show identification or sign a log.

“A group of Navy trainees went to the Black Nite on a dare, they knew it was a gay bar. … The Black Nite was targeted because it was a gay bar,” Buck said, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Takach said the Black Nite was able to openly cater to queer people because the owner paid the police for protection.

When the servicemen showed up and refused to pay or sign in, Takach said, the bouncer told them to leave and grabbed one of them by the arm, which led to a fight between the four men and the bouncer, who was Carter’s boyfriend at the time.

Carter, who was inside in her bathrobe, was a transgender woman of color, though Takach said she described herself as a “queen.” On that August evening, she heard what was happening and went outside with a beer bottle in each hand, “ready to knock some heads,” she told Takach in a 2011 interview.

“We didn’t start anything, but we sure as hell finished it,” she said.

One of the servicemen was injured, so the other three took him to the hospital, according to coverage of the event at the time by the two local newspapers, the Milwaukee Sentinel and the Milwaukee Journal. (The two papers would later merge in 1995 to become the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.)

Witnesses later told police that as the servicemen left, one of them said, “We’ll be back. We’ll return with some friends and clean up the place,” according to the Sentinel.

Takach said Carter began preparing for their return and urged patrons to fight back and defend the safe space they had created.

Her message was a timely one that resonated with the other queer patrons. Takach said it came about a year after police had beaten a man to death in a nearby public park that was known to be a meeting space for gay people. At the time, Milwaukee also had anti-crossdressing laws, which meant police would stop trans and gender-nonconforming people to ensure they were wearing three items of clothing that matched their sex assigned at birth.

But some Black Nite patrons were scared of potentially being arrested if they fought back, because most were not out and many had a wife and kids at home, Carter told Takach.

“And Josie’s like, ‘Who cares if you get arrested? It’s time to stop running and hiding, because this is never going to end otherwise,’” Takach recalled.

About two hours later, the servicemen did return with 10 to 15 friends, the Sentinel reported. Takach said they swung the door of the Black Nite open and yelled something. It was a “record-scratch moment” — the bar went silent, and all 75 patrons turned their heads to look at the door, he said.

The group entered and “started to tear the place apart,” according to bar employees, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported the next day.

The fight didn’t last long, according to Carter’s account. One man called her a homophobic slur, so she “popped him,” she said, and he fell to the ground.

“I’ll never forget that as long as I live,” Carter told Takach. “He started it, but I stopped it.”

After the fight, witnesses told police that the group of servicemen piled into two cars and drove off, according to local newspaper coverage. Three people were hospitalized (one serviceman and two bar patrons), and the next day, police charged three of the servicemen with disorderly conduct and searched for about a dozen others who they said “joined in an invasion” of the bar. The Black Nite’s owner, Wallace Whetham, estimated that the incident caused $2,000 in damages, the Milwaukee Journal reported.

About a year later, the Milwaukee Common Council declared the bar disorderly and ordered it to close due to the brawl, Takach said. But the owner of the building relicensed the bar under a new name, the Bourbon Beat, which operated until 1966, when the building was demolished to expand St. Paul Avenue.

Takach said the Black Nite brawl created a domino effect for LGBTQ rights in Wisconsin.

“It kind of triggered a cultural awakening,” he said. “Gay people knew where to go for the first time to find each other.”

The LGBTQ community in Milwaukee continued to expand in the ‘60s, and by 1969, Takach said there were 36 gay bars in the city.

On Feb. 25, 1982, the state became the first in the nation to make it illegal for state or private businesses to discriminate based on sexual orientation in employment and housing — nine years before another state would pass a similar measure. In 2012, the state would also be the first to send an LGBTQ person to the Senate when it elected Sen. Tammy Baldwin.

The Black Nite event, in addition to its effects on the state, may be the first recorded LGBTQ uprising in history, Takach said.

The first known LGBTQ resistance event was previously the Cooper Do-nuts riot in 1959 in downtown Los Angeles, but Takach noted that in recent years the one eyewitness of the riot recanted the story, and historians have noted that there are no other corroborating accounts or contemporaneous news coverage of the event.

“Unless there is evidence that something happened somewhere else earlier, Josie Carter’s decision might have been of national historic importance,” he said.

During the Oct. 5 event, Buck said that many people think of the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City as the catalyst of the gay rights movement.

“Although it’s little known beyond Milwaukee, the catalyst for this gay rights movement happened right here in Milwaukee eight years before Stonewall,” Buck said.

But Takach said Carter would laugh if someone said that to her.

“She has this very unique laugh, and I could just hear her saying to us, ‘Now, what did you go and do all this for? I told you, this was no big deal.’”