Dante Buu’s point of view is as unique as the pieces he’s producing for this year’s Venice Biennale.

His colourful embroideries are sculptural pieces affixed onto flexible metal rods which can be manipulated causing the pieces to change form. Buu himself is constantly morphing his forms of expression. Utilising video, performance art, photography, text, and textiles, Buu challenges notions of alienation, sexuality, intimacy, and identity.

His works will represent Montenegro at the 2022 ‘Olympics of the art world’.

“I am the first artist from a Muslim background to come out publicly as gay in the Balkans,” Buu states emphatically. “It’s a concept with specific wording that I use. Of course, there are others and I’m not denying their existence. It’s a question of making a declaration to the world.”

Hailing from Rožaje, which hugs the border with Serbia and Kosovo, Buu grew up feeling alone, due to his homosexuality and Muslim faith. Books and films were and still are his comfort.

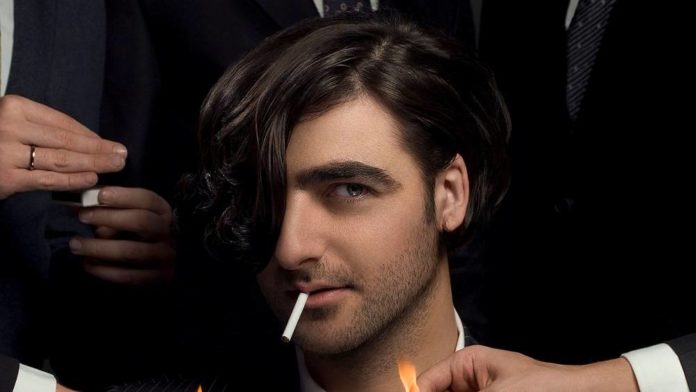

His loneliness comes through in the photograph ‘If you wanna fuck me you don’t have to pretend it’s for art,’ in which a dapper Buu is enveloped by suited men offering to light his cigarette. It’s a direct reference to the film ‘Malèna’ by Guiseppe Tornatore in which Monica Bellucci’s character pulls out a cigarette and men clamour to light it. In that moment, she resolves to be a prostitute in order to survive. Malèna’s husband is allegedly killed at war, she’s financially strapped. It’s a sterling moment, in Buu’s eyes, of self-empowerment.

“Every human being in this world is relevant. There is no supremacy of anyone. Unfortunately, we live in a world where wealth dictates supremacy.”

Minority in Montenegro

Coming out to his parents aged 14, he credits the support of his family with buttressing his sense of self. Buu also spent some time in Sarajevo before obtaining an artist-at-risk scholarship from the Martin Roth Initiative, arriving in Berlin in 2021. He still goes home to Rožaje regularly.

“I come from two minorities in Montenegro. I was constantly harassed and bullied as a child. In fact, there’s no difference between children and adults in that way.”

Buu considers his existence as resistance to uniformity, a sentiment that is born out in his works.

“I’m standing up for myself considering my background and then, dealing with the art world which also has misuse and abuse of artists.”

After coming from the margins, Buu has garnered major fellowships and awards. He became an artist-in-residence in places such as KulturKontakt Austria and the Ankara Queer Art Program. This autumn he will join CEC ArtsLink in New Orleans.

Most recently, he was selected for one of the foremost contemporary art residencies in Germany, Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Christoph Tannert, artistic director of the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, calls Buu’s art “true and beautiful.”

“He buries himself in the wounds of the soul,” notes Tannert “All he radiates is an almost tender humility that he shows to everyone who enters into dialogue with him.”

Performance art and social affairs

Buu’s performative works are meant to challenge our sense of intimacy as well as the art world’s focus on production and themes. He values durational performances because they aren’t just items to be bought or casually viewed without the artist present. For Buu, each performance is different, ineffable, impossible to duplicate exactly.

“He is driven by a will to truth that often goes so deep and is so existential that it leaves one speechless,” says Tannert

“The international art scene is characterised by routine. Dante Buu relies on disrupting the norm.”

One of his most searing performances took place in 2015 at < rotor >, a center for contemporary art in Graz, Austria. Called The Winner Takes It All, it features Buu in front of a video singing in monotone the famous ABBA song with its melancholic harmony, backed by two videos spliced together: one shows gay men joyfully dancing in a New York nightclub and the other, in sharp contrast, is from a YouTube video of a group of Russian men beating up a gay man.

Russian ‘gay hunters’ are known to lure gay men into attacks by going undercover in gay chat groups.

“It’s heartbreaking,” admits Buu. “The video is at once the executioner and victim. It’s what happens in life. We all have personal responsibility to each other, but I find that people don’t. There is a point in the video on YouTube where one man tries to stop the beating, then they explain to him why they’re doing it and he joins them.”

At the Bethanien in Berlin, Buu confronted the public with two performances. One, called ‘and you—do you die happy?’ featured Buu in a window, standing mid-phone call with teary mascara running down his face, four hours a day for eight days. A performance he repeated twice at different locations in the city. While in ‘thigh high,’ he exhibited some of the embroideries he’s worked on since 2020 whilst he exhibited himself standing still for 27 days, five hours a day.

“I am obsessed with time and what it means for artworks. With the performance, we see the time, but the artwork is fleeting. With embroidery, we see the result but have a fleeting idea of the time that went into production—the first one I ever did took four years,” says Buu.

Buu’s embroidered work began in 2014 after his father fell from a cherry tree. While his mother waited in hospital for his father to wake up, Buu, who witnessed his grandmother, aunties and mum embroider throughout their lives, began a piece in all black. It ended up being 2 metres long.

Embroidery and class in Montenegro

“It is a craft that is denigrated because if you’re poor in a place like Montenegro, you have to make things, and the women did this—it’s also part of their dowry. It’s the kind of female labour that’s rendered invisible.”

Buu has invited his mother, in anticipation of the Biennale, to create a new embroidery piece. She begins on one end and they meet in the middle. They take anywhere from three months to years to finish depending on their varying sizes.

“I just tell her to choose the colours randomly and to go with her feeling. There is no planning and she’s the only one who can do this.”

Five of Buu’s pieces will feature in Montenegro’s contribution at the Venice Biennale from April to November.

It’s been a tough journey from Rožaje to the Biennale, where Buu’s work will be in the international spotlight, but he remains steadfast, reluctant to cater to the mainstream.

“Artists often have to say they are influenced by so-and-so–from the canon of Western, European art by straight, male artists. But what is the history of art? It’s not that.

“It’s something we have been sold and it’s not the truth.”