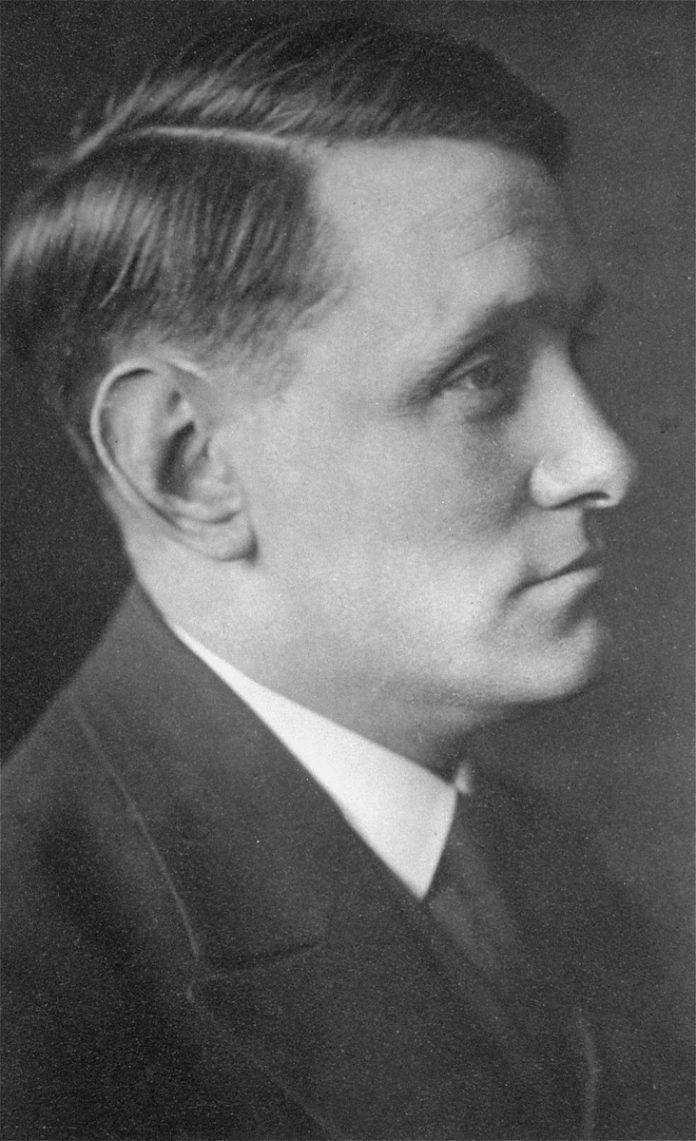

In the final days before his execution in July 1943 at the hands of the Nazi party, Willem Arondeus asked his lawyer for one last request: to spread a message after he was gone.

“Let it be known,” he said. “Homosexuals are not cowards.”

Related: Disneyland wouldn’t let same-sex couples dance together until a gay teen sued in the 80’s

A battle cry of defiance and a bold assertion of his strength, Arondeus lived his life by these words. An openly gay man and a tireless member of the Dutch resistance against the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, he willingly sacrificed his life for a mission that ultimately protected hundreds of thousands of Jews’ lives.

A budding artist struggling to survive

From an early age, Arondeus was no stranger to the concept of defiance.

Born in 1894 as the youngest of six siblings in Naarden, Amsterdam, Arondeus began to have constant fights with his parents over his sexuality.

Often deemed the birthplace of LGBTQ rights, Amsterdam decriminalized homosexuality in 1811, but restrictive rules still barred homosexuality in the early 20th century.

In 1911, the beliefs of the ruling political parties led to the age of consent for homosexuality to be changed to 21 in the Netherlands — despite the age for heterosexuality remaining at 16. Despite the first gay bar opening its doors during this time, these restrictive age rulings, along with other laws against public indecency, were used to unfairly target gay men.

But these rulings did not intimidate Arondeus. He refused to suppress his identity as a gay man, leaving home that year at age 17 and severing ties with his family.

Picking up work where he could find it, Arondeus struggled financially but continued to pursue his passion for writing and painting for the next three decades — going on to complete a mural for the Rotterdam Town Hall in 1923, and, later, writing a biography of Dutch painter Matthijs Maris in 1938. During that time he met his partner, Jan Tijssen, with who he lived for seven years.

Arondeus quickly learned, though, that persistent discrimination of LGBT citizens made life difficult. Alongside living in poverty, he also struggled to find housing due to his refusal to hide his sexuality.

“Willem, as an exception, lived as openly as he could,” Klaus Mueller, the European representative for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, said during a virtual event “Pride Month: Defying Nazi Persecution” this past July. “In his diaries… he wrote about being kicked out of apartments because he was gay, there was no protection.”

A calling to activism

While Arondeus had many artistic talents, he is much more recognized for his courageous acts of rebellion as a member of the Dutch resistance during World War II — which he joined in 1940 and where he truly found his voice as an activist.

“When you read [his] diary you see an insecure artist, even doubting his own success… he always felt as an outsider,” said Mueller. “But when he joined the resistance, he found his own voice — you see a man who is determined, who knows the risks, but doesn’t feel like an outsider anymore.”

Though Arondeus was focused on defending the safety of the Dutch Jews, he and other LGBTQ citizens also saw the imminent threat of the Nazis to their community.

Upon their occupation of the Netherlands at the start of the 1940s, the Germans brought with them Paragraph 175 — a law first introduced by Hitler in Germany in an effort to cleanse the country of homosexual activity. The ruling, which first began by expelling any gay and lesbian organizations in Germany, was revised to make homosexual activity between men punishable by imprisonment. Even the slightest bit of suggested evidence could send them behind bars, and as a result, over 100,000 German men were arrested and 50,000 were imprisoned.

Further, over the course of the Nazi rule, it is estimated that between 5,000 and 15,000 gay men were sent to concentration camps. Marked by pink triangle badges, they were brutally abused; and many underwent experimental medical treatments aimed at curing their sexualities.

Cognisant of this dire threat, Arondeus sprang into action right at the start of the Nazi occupation. Along with publishing anti-Nazi information, he and other members of the resistance created about 70,000 false identification cards of Dutch Jews — preventing them from being tracked down by the Nazis.

Yet over time, the Nazis began to catch on to the forged documents, which could be double-checked at the Amsterdam registry building.

Arondeus and the rest of his unit constructed their riskiest plan yet: they would blow up the facility — along with the hundreds of thousands of documents inside.

Frieda Belinfante, an openly gay woman who fought alongside Arondeus in the resistance and participated in the plan, said that while both of them knew the danger that would come if they were caught, each knew it was necessary to carry out their mission.

“He said, ‘Do you think that we see the end of this war?’ and I said ‘I don’t think so’ and he said ‘I don’t think so either,’” Belinfante recalled in a conversation the two had about the danger of their plan. “And then he said ‘Do you mind?’, and I said ‘No I don’t’, and he said ‘I don’t either.’”

And so, on March 27, 1943, a group of resistance fighters led by Arondeus entered the facility disguised as Dutch police, drugged the guards, and blew up about 800,000 identity cards.

Yet, just several days later on April 1, an anonymous source informed authorities of the attack and Arondeus was arrested. Though he attempted to take full responsibility for the attack and refused to give the names of his team, his notebook was found and many of the contributors were revealed.

Some were able to escape and flee the country, but exactly three months later, Arondeus and 12 others — including two other gay men — were brought before a firing squad and executed.

A legacy overshadowed

Though the bombing of the Amsterdam registry building was widely regarded after the Holocaust as a lifesaving moment in history, education about the heroic moment omitted Arondeus’ leadership due to the fact that he was a gay man.

So, while his family did receive a medal of honor for his sacrifices in the years following his death, homophobia that persisted throughout the 1950s and 1960s prevented LGBTQ war heroes like Arondeus from getting the recognition they deserved. This went against Arondeus’ final message to his lawyer for the public to be informed of LGBTQ participation in the mission.

It was only in 1984 that Arondeus was awarded the Resistance Memorial Cross, and in 1986 that he was posthumously declared a Righteous Among the Nations honor —given to those during the Holocaust who were not Jewish but protected the rights of Jewish citizens in need.

And in 1990, he finally got his wish to be recognized not only as a hero, but as a member of the LGBTQ community. His sexuality was revealed in a TV program, and the Dutch public finally learned the true extent of his bravery — forever cementing his efforts as a symbol of heroism in the LGBTQ community for years to come.

“He was a great hero who was most willing to give his life for the cause,” Belinfante said.

To learn more about Willem Arondeus, visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website and YouTube page.