/UnemploymentRates-b0470f0972f548b8b2b6fbd289e58d32.png)

Although it has received less attention than other notable pay gaps, data shows that pay gaps exist for LGBTQ+ communities in the United States. National studies of discrimination in the private and public sectors have noted widespread employment discrimination going back decades against LGBTQ+ workers, especially against transgender and bisexual workers.

Income inequality refers to an uneven split of income that favors some segments of the population over others. Income inequality connected to discrimination also impacts a variety of job-related areas—including productivity, job satisfaction, earned wages, and job opportunities—as well as other conditions related to prosperity like health.

A pay gap refers to a difference in the average pay between two groups of people. This article will focus on the pay gap between LGBTQ+ people and heterosexual people. Despite recent progress, the data shows that LGBTQ+ communities continue to face discrimination and disparities in income and unemployment.

Key Takeaways

- The LGBTQ+ pay gap refers to the disparity in earned income of typical households across sexual orientation and gender identity.

- LGBTQ+ communities continue to face discrimination and disparities in income and unemployment.

- Job protections for LGBTQ+ are new.

- Laws and court decisions such as the 2020 Bostock v. Clayton County Supreme Court decision affect progress by guaranteeing job protections, but activists say there’s still work to do.

The Broad Picture of the LGBTQ+ Pay Gap

Before 2017, most studies concluded that gay men faced a pay gap and that gay women earned more income than straight women, although these studies received some criticism for their exclusion of bisexuals and for their embracement of binary views of sexual orientation, which may have obscured the role of family arrangements at play in these observed wage trends.

A Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law report, which surveyed all the available evidence as of the summer of 2011, established that LGBTQ+ workers in the United States had seen staggeringly high rates of discrimination and harassment in the workplace, including the loss of jobs, across both the private and public sectors for the four decades leading up to the report. A review of public sector surveys detailed in the report, for example, showed 380 documented examples of workplace discrimination against LGBTQ+ people in all branches of government across 49 states, including harassment, slurs, threats, and physical violence.

In general, the report said, homosexual men tended to earn less than heterosexual men, and bisexuals tended to earn less than gay or straight people. In contrast, many studies have concluded that lesbian women tend to earn more than heterosexual women, including a 2014 meta-analysis by Marieka Klawitter of the University of Washington that looked at 29 studies.

Reporting on these trends from 2015 suggested a “wage hierarchy” with heterosexual men receiving the most pay, gay men the next most, followed by lesbian women, and then heterosexual women. It is important to note that the factors influencing these gaps are complicated and that there are also pay gaps within and across these categories, especially when accounting for the impact of COVID-19.

Noteworthy Progress

For some LGBTQ+ groups, in some limited categories, the pay gap seems to have narrowed in recent years. National Health Interview Survey data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control began to show, for the first time from 2013-2015, that gay full-time employed men earned 10% more than similarly employed straight men, controlling for other factors like age, ethnicity, presence of a partner, etc., according to a 2017 study from researchers at Vanderbilt University.

Previous studies had shown that gay men were paid less, even after they controlled for intervening factors. It is important to note, however, that gay men in the study also had lower employment rates than straight men. The Vanderbilt study also reconfirmed that lesbian women made more than straight women, or what is referred to as the “lesbian wage premium.” The reasons for this are somewhat unclear and are debated, but the authors of the Vanderbilt study suggest that it is probably not because of reduced discrimination or changing patterns of household specialization.

The Vanderbilt study also showed the continuation of pay disparities for other LGBTQ+ communities. Bisexual men and women, for example, earned less than gay or straight men and women.

Moreover, studies of earnings of transgender individuals have consistently reported lower income, high rates of discrimination and harassment, and high rates of unemployment. Transgender individuals also face exceedingly high levels of discrimination. According to the San Francisco LGBT Center, for instance, 50% of trans people say they were unfairly fired or denied employment, and 78% say they face harassment at work.

Reasons for the LGBTQ+ Pay Gap

Discrimination and uninclusive workplace climates deserve a share of the blame. The Williams Institute report, which looked at surveys of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people, says that 42% of the people in these communities reported having been discriminated against because of their sexual orientation, with about 16% reporting that they had lost their job because of it.

Transgender people, when surveyed separately, reported even higher levels of discrimination. The Williams study, for instance, reports that 78% of transgender people had faced discrimination in 2011. Almost half of all transgender respondents said that they had suffered from discrimination connected to job retention, hiring, or promotion.

Other factors also play a role. For instance, the rates of discrimination will typically differ by region and by workplace. While 44% of people in national surveys from 2009 reported discrimination, 19% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans staff and faculty at universities and colleges across the country reported having suffered discrimination, suggesting that perhaps academic workplaces may be somewhat less discriminatory.

To compare differences even further by region, in 2010, 43% of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in Utah said they had been discriminated against, compared to about 27% of lesbian and gay people in Colorado. The picture is further complicated by intersecting factors that affect pay, such as race and ethnicity, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unemployment and COVID-19

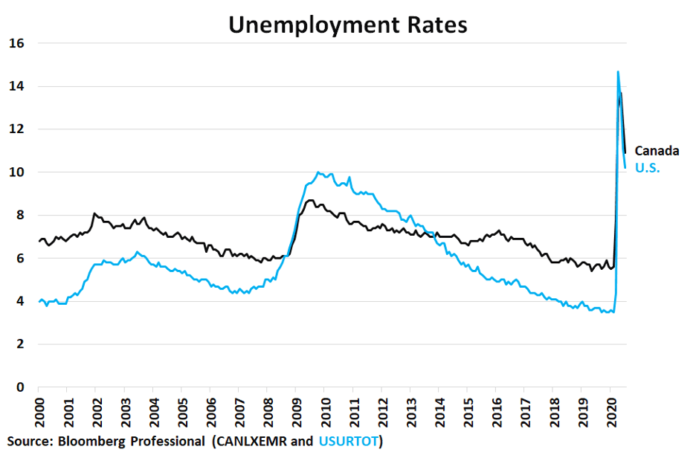

COVID-19 drove up unemployment rates for LGBTQ+ communities, especially for LGBTQ+ people of color and transgender communities. Activists and watchdog groups have warned that this threatens to further tilt an already unequal situation in the U.S. and across the world.

Importantly, researchers have highlighted that the bulk of the government data on COVID-19 does not incorporate sexual orientation and gender identity measures. This makes tracking the effects or including these communities in recovery efforts more difficult.

A Human Rights Campaign poll from 2020 indicated that, based on the impact of the first wave of the closures, 17% of LGBTQ+ people had lost jobs because of COVID-19, which was higher than the 13% of people who had lost jobs in the general population. People of color in LGBTQ+ communities, particularly Black and Latinx people, were more adversely affected, reporting a 22% job loss for people of color in LGBTQ+ communities and 14% for Whites in those communities. LGBTQ+ people of color were 44% more likely to take a cut in work hours, and transgender people were 125% more likely to do so.

Researchers attempting to put the findings in context told the Philadelphia Inquirer that LGBTQ+ households work in industries that were more severely hit by COVID-19, such as the hospitality sector and the survival gig economy. While there isn’t much data or analysis on these trends yet, reports on the LGBTQ+ community in general hold that COVID-19 exaggerates underlying vulnerabilities: These communities are more likely to live in poverty, more likely to work in industries negatively impacted by COVID-19, more likely to suffer from underlying conditions, and more likely to lack access to medical care or paid medical leave.

Laws that Affect Progress for LGBTQ+ Workers

When some of the studies mentioned in this article were conducted, LGBTQ+ people had no protections against discrimination in employment. Protections against employment discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity had mostly fallen through legislative gaps in civil rights protections.

The Employment Non-Discrimination Act, for instance, first introduced to Congress in 1994, failed to pass despite numerous reintroductions. It would have written the protections against employment discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity into civil rights laws. There was support from the Obama administration around the time for a version of the bill introduced by Senator Jeff Merkley, which passed the Senate in 2013. Acting Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division Jocelyn Samuels, for example, praised the bill, commenting that its passing would “move this great nation one step closer to fulfilling our Constitution’s promise of liberty, opportunity, and equality for all.” However, the bill died in the House.

During the Obama administration, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had included LGBTQ+ discrimination claims, but these protections aren’t specifically written in the law, leaving LGBTQ+ people vulnerable to executive whims of how to interpret existing laws. The Trump administration reversed this, setting the scene for a Supreme Court case.

In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act extends protections against employment discrimination to LGBTQ+ people, in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia. According to the Supreme Court decision, protections against discrimination due to “sex” include sexual orientation and gender identity. Many states did not offer these protections at that time. On January 20, 2021, President Biden issued an executive order to fortify the decision.

Laws that extended marriage rights, such as 2015’s Oberfell v. Hodges Supreme Court decision which legalized same-sex marriage, are worth noting as well. While this ruling did not directly affect the pay gap for LGBTQ+ people, the financial benefits were enormous. After legalization, same-sex spouses could file taxes jointly and legally receive payouts from their spouse’s retirement accounts without the tax burdens or issues faced by unmarried couples.

The Bottom Line

The 2020 Bostock v. Clayton County decision occurred against a backdrop of rights rollbacks for LGBTQ+ communities. The Trump administration had overseen pushback against the extension of rights to LGBTQ+ people, in part through the extension of religious exemptions to civil rights legislation.

The administration was criticized by pro-LGBTQ+ organizations for a litany of actions that encouraged income inequality, including appointing anti-LGBTQ+ judges, opposing the Equality Act, banning transgender people from serving in the military by citing “health costs,” filing court briefs to support discrimination practices, expanding religious exemptions to federal contractors, and other policies that touched on nearly all spheres of life for LGBTQ+ communities.

Since then, some of these have been reversed by the Biden administration, such as the transgender military ban. The rapid rollbacks in LGBTQ+ protections by the Trump administration and the reversals by the Biden administration point out the vulnerability of these rights and protections. This underlines the importance of Supreme Court rulings and federal laws when it comes to protections for LGBTQ+ people.

With new protections for LGBTQ+ people, perhaps the next decade will see improvements in pay and employment inequality. Despite progress in some areas, activists say that a lot of work remains to secure income and employment equality for LGBTQ+ workers. Some of this work could be achieved by passing the 2019 Equality Act, says Human Rights Watch.

- The Equality Act would alter the language of the civil rights legislation to explicitly ban discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

- The Paycheck Fairness Act, which other advocacy groups have argued for in order to close the gap created by wage discrimination, would update the 1963 Equal Pay Act. If passed, it would broaden the scope of the Equal Pay Act, clarify some of the language around its provisions, strengthen the remedies for victims and the oversight mechanisms, ban employer retaliation for employee wage disclosure, and also make class actions easier to bring in gender wage discrimination cases.