Since completing my Ph.D. in biochemistry and biophysics in the fall of 2021, I have been road-tripping around the United States with my wife, who is a deep learning engineer and an immigrant from France. As scientists and a bicultural, queer couple, we are constantly weighing our career, lifestyle and travel options and limitations.

The demands of research often force scientists to move every few years and to travel regularly for research or conferences, and where we go to follow opportunities is typically out of our control — it’s determined by the location of the field site, instrument, collaboration, conference or job opening. One scientist, Anita Di Chiara, told me, “I feel like I do not have the freedom to choose where I go. To choose where I go, I would have to leave academic research.”

These travel demands can weigh heavily on any scientist, but those in the LGBT+ community face additional hurdles; cultural acceptance and laws can vary dramatically among states and countries. Questions expand beyond “will I like the food and weather there?” to “is it safe for me to be myself?,” “will I have access to the health care I need?,” “is there a dating pool for me?” and “will I legally be my son’s mother?”

LGBT+ scientists consider questions like these at every stage of their academic careers, so I spoke with eight LGBT+ scientists from the undergraduate level to professors to find out how location has guided their professional life.

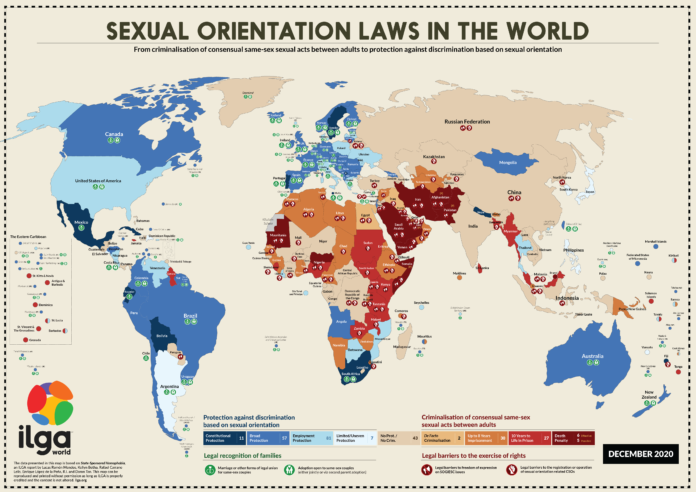

ILGA World

Undergraduate to graduate school

Lisa Coe is a laboratory technician at New York University Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, a country where homosexuality is punishable by law. Coe, who identifies as queer, moved to the UAE for her job after completing her bachelor’s degree in microbiology in the United States in 2020. Before she moved, the university put her in contact with someone in the department who is openly gay so she could ask him questions.

Despite cultural obstacles, Coe has formed a queer community in the UAE through the on-campus pride group and dating apps. She said she benefits from the globalized area she’s in and the privilege that comes with being from the U.S. After having an incredibly supportive advisor during her undergraduate research and then living within a culture that is more difficult to navigate as a queer individual, Coe is carefully considering her graduate school location and advisor options that work for her and her partner.

Two trans men in Europe, who asked to remain anonymous, told me about the factors that influenced their decisions about where to go to graduate school. Both said they had significant concerns about health care options. “I can only look at places with universal health care because my medication is expensive,” one man said.

Not only is cost a huge concern, but the paperwork involved in obtaining needed health care can be limiting, overwhelming or difficult to navigate. In many European countries, the process to receive hormones includes a diagnosis or letter from a doctor, which often requires long wait times and is not necessarily transferable to another European country. One man told me that even though he was excited about a research project in another country, he can’t go there because of these limitations. “Sometimes it’s better to take a better work environment over research,” he said.

Another concern raised by one of the men was consideration of surgeries in regards to trans health care. These typically come with assessments and long wait times, and sometimes must be completed in several stages; to get them done, a person will probably need to stay in one place for more than the few years that most academic positions last.

To further complicate the situation, one man spoke to me about being unable to attend a conference that would have been important for his professional development and networking because it was held in a country that would not allow him to enter as a trans person.

“Maybe conference organizers just don’t think about it,” he said, but he does not have that luxury.

Graduate school to postdoc

Boomer Russle is a third-year Ph.D. candidate in the biochemistry and cellular and molecular biology department at the University of Tennessee–Knoxville, and he has always lived within a single two-hour driving radius in Tennessee. He is comfortable being out as a gay man and has a great support system, but the queer community in this region, and consequently the dating pool, is small and limited compared to other places in the U.S.

Russle loves his department, but their decision to stay so close to home for undergrad and his Ph.D. was largely driven by financial limitations and family obligations, not by dating prospects. Of course, dating isn’t a priority in graduate school, he said, but it does often overlap with the time in people’s lives when they find a life partner.

“People don’t apply to grad school thinking about what stage of life they’ll be in there,” he said. “If I had thought about it, I would’ve applied to other places not in the Bible Belt.”

Russle plans to try to move to a new place for his postdoc, but he said he wouldn’t be surprised if he ultimately ended up back in a place similar to Knoxville because it is so important for queer people to show up and stay in these regions to advocate for other members of the community and to be role models for other upcoming LGBT+ scientists.

Postdoc to professor

Ranen Aviner, a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University and the University of California, San Francisco, is now looking for a faculty position. Aviner moved to San Francisco from Israel for his postdoc, and he said that navigating academia is already difficult, but being gay adds an additional layer of frustrating difficulties.

Aviner’s partner is also in academia, so they have to navigate the difficulty of two partners securing academic jobs in the same area, commonly referred to as the “two-body problem.” And to complicate the situation further, if Aviner were to move back to Israel for his next step, they would have to face new legal, distance and cultural challenges to stay together. Because of these complications, Aviner said, “I can’t think about the next step, about where the science takes me, because it comes with loss. It’s a really emotional decision.”

Additionally, Aviner has enjoyed living in San Francisco, where being gay is well accepted, so it isn’t something he worries about much. He said that feeling accepted and safe frees up mental space for other things, and he’d like to remain in an accepting environment. “There’s no point in adding additional stress and burden,” he said.

Up to this point in his career, Aviner has noticed that many people in university systems view LGBT+ diversity statements as simply performative and think that being a part of the LGBT+ community shouldn’t matter in the workplace. The responsibility often falls on LGBT+ people to explain how they bring diversity, he said, when universities should be asking what they can do to help people in the LGBT+ community overcome barriers. “It’s disrespectful to think that you shouldn’t bring this into the work environment,” he said, “because people talk about their families.”

Anita Di Chiara is a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology in Rome, Italy. Through her Ph.D. and four postdocs, she has lived in Italy, the United States, Brazil and England. Beyond moving every few years, Di Chiara has also had to travel extensively for fieldwork, often to places that are not welcoming to the LGBT+ community. She is always very careful and tries not to draw attention to herself, she said, and if her partner is traveling with her, sometimes it’s best to let people think they’re sisters.

In particular, Di Chiara found an accepting environment in San Diego, where for the first time she was able to come out as a lesbian to her supervisor, and in São Paulo, Brazil, home to the largest Gay Pride Parade in the world.

Due to the pandemic and visa issues, Di Chiara and her partner had to move back to Italy, which she said was an especially difficult transition after becoming accustomed to more inclusive environments. Although same-sex couples can obtain a civil union in Italy, marriage is still not legal, and adoption or surrogacy is not an option for same-sex couples in Italy who want to be parents.

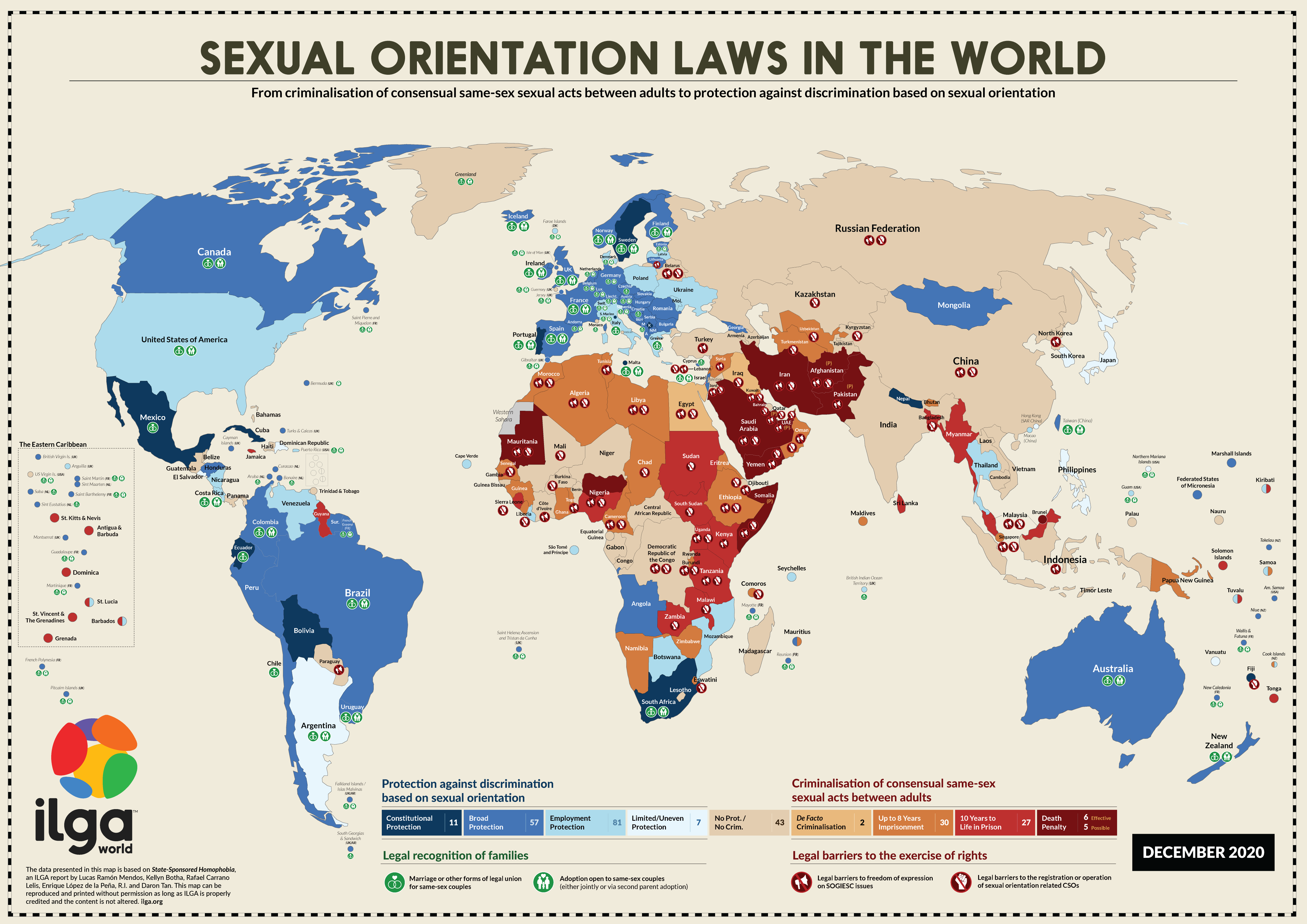

Movement Advancement Project

Beyond the postdoc

Within the United States, as well, marriage and parenthood laws can dictate where queer families can live comfortably.

Katie Thompson–Peer, an assistant professor in the developmental and cell biology department at the University of California, Irvine, said laws regulating the LGBT+ community have influenced her decisions since choosing graduate school. She went to Harvard University for her Ph.D. because Massachusetts was the only state at the time where she and her partner could get married and share legal benefits such as health care. She then moved to San Francisco for her postdoc — by that time, California also acknowledged her marriage

Even after gay marriage became legal throughout the U.S., Thompson–Peer knew that state laws governing parental rights could make a huge difference in her life. Although both parents may be listed on the birth certificate, this administrative document is not protected by the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the U.S. Constitution, meaning that other states are not required to recognize it, and not all will

To guarantee legal recognition by other states, Thompson–Peer had to go through second-parent adoption procedures, which can be long and expensive, and vary significantly among states. Additionally, she wanted to make sure her son would grow up in an environment that embraced their family.

“In California, he’s not the only kid who has a family structure that is reflective of ours,” she said. “It’s one thing to put myself in these situations, but it’s another thing to put my kid in these situations.”

Thompson–Peer was lucky enough to have faculty options in California, where the legal proceedings were manageable and she knew her son wouldn’t constantly have to explain his family structure. She loves her position at UC Irvine, which was also the only place she interviewed that put her in contact with an equity officer during the interview process.

Sharon Collinge is a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder and the executive director of the school’s Earth Leadership Program. Collinge identifies as a lesbian but kept this identity to herself through her undergraduate and master’s degrees. Being in the Midwest at the time, she didn’t have many scientist role models to look up to, let alone queer scientists, but she said she still misses the midwestern lifestyle.

“I grew up in a fairly small town, and I love the small-town life and the values, and connection with nature, and I still can’t live in those towns in the U.S.,” Collinge said. “They’re mostly not welcoming to LGBT+ people … and that makes me sad.”

After moving to Boston and pursuing her Ph.D. at Harvard, Collinge was able to start being more open about her identity. She took this into consideration when applying to postdoc and faculty positions later. “I was super-excited, not only for a great job, but to find my people,” she said.

Collinge is happy and comfortable in Colorado, but she has also had to travel extensively throughout her career, including a sabbatical in Tanzania. Living in the traditional culture there, she couldn’t share much about her personal life. “When you can’t be who you are, then you feel like you’re missing half of your body,” she said.

Even as a tenured professor, she still thinks about these issues when meeting new people and visiting new places, because simply sharing that she has a wife can shut down conversations.

“I wish I could just be me and just show up,” she said, “but it’s still complicated.”