If you ask Sophie Smith why she switched elementary schools, the reasons are simple: gender and name. Sophie, whose name has been changed for this story to protect her identity, wanted to be referred to with the pronouns “she” and “her” and called Sophie — and then get back to doing what she loved, like creating art and hanging out with friends.

At home, that’s exactly what happened. Even though Sophie was assigned male at birth, her parents listened when at age 3 she told them she was a girl. Experts from the Mayo Clinic to the American Academy of Pediatrics say from a young age, kids can identify their gender — and whether it matches what’s on their birth certificate.

At school it was a different story.

“[Other families questioned] how I was parenting her and [wanted me] to guide her to a different way,” Sophie’s mom said. “I think they were trying to pray for us, like pray the gay away.”

At an Omaha Catholic elementary school, Sophie was misgendered by teachers and bullied by classmates for wearing a dress to an event. When Sophie’s mother asked that her daughter be referred to with she/her pronouns and wear a girl’s uniform, a priest said no. God makes us as we are, Sophie’s mother remembered him saying. It was non-negotiable.

“I believe the very same thing,” her mother told the priest, “that God makes us who we were meant to be, [which means] you can be you on the inside. It’s not just the external parts of your body that make you [who] you [are].”

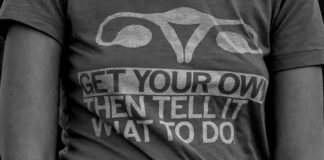

Nationwide, transgender students have become a magnet for politicians, television pundits and countless social media keyboard warriors. Omaha’s no exception. The initial drafts of suggested statewide sex education standards, which mentioned gender identity, coalesced into a political proxy war, and the word “transgender” wound up nixed from the drafts (see our story here). And, as the school year kicks off, teachers and parents battle over whether educators should ask students to share their gender pronouns. But many feel we’re missing the most obvious fact: They’re just kids.

“Little trans girls are not out to get anybody,” said Dr. Jay Irwin, a medical sociologist and sociology professor at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. “I don’t know when [trans people] became so scary.”

Experts, parents and transgender kids themselves say they aren’t doing this for sports, bathrooms or pronouns. They’re doing it because trans kids know who they are, and they want the rest of the world to see them that way.

When it doesn’t, when parents, schools or friends aren’t accepting, it can lead to bullying and mental health crises, including higher suicide rates. But that’s not everyone’s experience. Sophie transferred to Millard Public Schools, which has a non-discrimination policy that includes gender identity. Teachers and kids treat her like the girl she is, her mom said.

“Everybody was scared of Sophie at the last school. They were basically trying to protect all the other kids from Sophie,” she said. “Now they’re protecting Sophie.”

Science and Controversy

As they returned to class for the new school year, local high schooler Jamal Webber was focused on getting good grades and bracing for the usual teenage social drama. Jamal, whose name was changed for this story to protect their identity, wasn’t thinking about being out as trans and nonbinary in a sea of teenagers.

That’s because their friends were supportive, and the rest of their classmates didn’t really care much.

“People are like, ‘Whatever,’” Jamal said of their classmates. “Students are generally really chill with it.”

Someone’s gender identity shouldn’t be controversial. And for kids, Irwin said, it usually isn’t. According to children’s health experts, before kids can read and write, they begin to form a gender identity. And if it doesn’t match what’s on their birth certificate, so be it.

According to Irwin, telling a kid like Sophie she can’t wear a dress or play with dolls because of what’s on her birth certificate isn’t based on science or biology. It’s a rule made up by humans that can prove confusing to even cisgender kids (whose gender matches the sex on their birth certificate).

“Elementary schoolers [ask], ‘I’m supposed to play with these kinds of toys, but I can’t play with these kinds of toys? Why? They’re toys,’” Irwin said. “Those seem like arbitrary rules to kids.”

Sophie’s younger sibling understands her big sister’s gender. When she sees old photos of her older sister, she matter-of-factly says, “That’s when Sophie was a boy,” but she knows Sophie is a girl now.

Trans kids just want to mind their own business and have normal childhoods, Irwin said. What they don’t want are classmates, teachers and parents looking at their clothes or wondering what’s underneath them. How we feel in our bodies is intuitive and natural, according to experts like those at the American Medical Association. Trying to argue or rationalize it is a losing battle.

“People deserve to present as their authentic selves,” said JohnCarl Denkovich, a longtime LGBTQ+ activist in Nebraska. “It really is as simple as that.”

Title IX, School Guidelines and the Gospel

The Archdiocese of Omaha Catholic Schools defines “authentic” differently.

“First and foremost, we abide by what the gospel tells us,” superintendent Vickie Kauffold said. “That’s [our] identity; [that’s] who we are.”

The gospel, she said, explains God created male and female. According to the Archdiocese of Omaha’s Evangelization and Family Life Office, there’s no differentiation between body and soul, nor gender and body.

The Family Life Office says it offers patient, loving guidance to students questioning gender identity. But they’ll affirm reality — which they consider the sex on the child’s birth certificate — and not the child’s new pronouns.

Kauffold said an individual school within the Archdiocese could technically affirm a child’s gender identity, but most would seek guidance through the Family Life Office. The Archdiocese recognizes that children might leave Catholic school when their pronouns aren’t affirmed.

“We love these kids,” Kauffold said. “It hurts us to see kids want to walk away from the church [and] from how God designed them to be.”

Sophie said that when Catholic school wouldn’t affirm her name and gender, it made her feel bad. When The Reader asked her in an email interview how she feels now that her Millard classmates and teachers treat her like a girl, the elementary schooler’s response wasn’t complicated:

“Grrrrreat.”

Unlike private schools, public schools are required to follow Title IX, a civil rights law passed in 1972 that protects students from sex-based discrimination. As of June 2021, that includes protecting students on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation.

Omaha Public Schools has four pages of gender identity equity guidelines, which define terms like “gender fluid” and “transgender,” and outline how the district affirms a child’s gender.

Ralston Public Schools lists gender identity, in addition to gender expression, in its notice of non-discrimination. Irwin, himself transgender, serves on the Ralston Schools Board (according to the Omaha World-Herald, Irwin is believed to be Nebraska’s first openly trans elected official), and said it was his idea to add gender identity.

But rules don’t make safe environments for kids. Teachers, administrators and other students do.

“At the end of the day, the student really only knows … what they’re experiencing in school,” Denkovich said, “and whether or not those policies translate into practice.”

Guidelines on the Ground

Denkovich attended public school in Lincoln in the late 90s and early 2000s and describes their high school years as horrendous.

“I had food thrown on me, I was spit on, I had my stuff stolen, people keyed the word ‘fag’ into the hood of my car,” said Denkovich, who as a result often experienced panic attacks for years when eating in public and still lives with severe social anxiety. “I was suicidal … I didn’t think I would live to graduate from undergrad.”

Denkovich, who was inspired by their mother to channel their trauma into LGBTQ+ advocacy work and activism in college, is a proponent of statewide anti-bullying laws that specify protections for historically marginalized groups like the LGBTQ+ community. Currently, Denkovich said, protections for marginalized groups, which aren’t explicitly covered under Nebraska’s anti-bullying law, are optional.

According to research from the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, LGBTQ+ students who attend schools that have enumerated policies, which explicitly state that they protect marginalized groups, experience less bullying than those whose schools — like Nebraska’s — do not.

In Catholic school, most of Sophie’s classmates refused to use her pronouns and chosen name. When Sophie wore a dress to a church event, kids made fun of her, and the school changed its dress code so kids had to wear clothes that aligned with the sex on their baptismal certificate for future events. And when Sophie came to school with a Disney princess backpack, a mom called the priest and requested he talk to Sophie’s mother about appropriate parenting.

“Bullying doesn’t just come from students,” Denkovich said. “It can come from other parents; it can come from administrators and educators.”

Then there was the girls’ bathroom, which Sophie wasn’t allowed to use. Dr. Ferial Pearson, a University of Nebraska at Omaha teacher-education professor and activist, has seen kids lose class time walking to a single-stall bathroom, or get urinary tract infections from holding it all day because they’re scared of physical assault. According to a recent American Academy of Pediatrics study, roughly 36% of trans and nonbinary teens surveyed whose schools restrict bathroom or locker room access had been sexually assaulted in the past 12 months.

“People worry [trans girls are] pretending to be girls so they can molest somebody. There’s no record of that happening,” Pearson said. “But what we have seen [nationally] is trans kids being attacked in bathrooms.”

At Jamal’s school, there is a gender-neutral restroom, but kids need a separate key for it. Unless they’re connected with the right advocates, they’ll never know it exists.

Jamal’s school has been affirming overall; nevertheless, they encountered a teacher who insisted that “they/them” is plural, not singular, and misgendered them the entire semester.

“If the teacher gets [your pronouns] wrong and refuses to get it right, you just have to sit with it,” Jamal said.

Transgender students in supportive settings are still up against what Irwin describes as death by 1,000 paper cuts. Misgendering or deadnaming someone (calling a transgender person by their former name), even when unintentional, messes with students’ minds. Irwin said seemingly innocuous gendered comments like “You go, girl!” or “Do you have a boyfriend?” can make trans kids feel like they stick out like a sore thumb.

“It’s a constant reminder of, ‘Oof, I’m not fitting in. Do I want to stand out from the crowd, or do I want to conform?’” Irwin said. “Conformity comes with a price.”

Jamal’s mother worries how gender segregation in schools — separating boys and girls in sports, bathrooms, prom court — will affect Jamal. She wonders whether the PE teacher will place them with the boys or girls for swimming, and hopes homecoming “queen and king” will become “royalty.” Jamal, who plans to try out for tennis, is concerned they’ll be forced to wear a skirt.

Sports are another minefield. The Nebraska School Activities Association (NSAA) allows transgender students to play sports — after they’ve undergone a convoluted process, including official confirmation of the student’s gender identity by parents and peers, potential submission of medical records, review of an application by the NSAA’s Gender Identity Eligibility Committee, and more. Even if a student wins, they still must use the bathroom associated with the sex on their birth certificate if they haven’t had sex reassignment surgery.

“I’d argue that the majority of trans students will never exercise this policy because of how invasive it is and the hoops required to jump through in order to play,” Denkovich said. “And there’s no guarantee that if you submit all this that you’ll even be approved.”

Every school should accommodate trans students, advocates say. That can be as simple as desegregating activities based on gender or educating the class on pronoun usage. But, according to Denkovich, some parents and educators argue only LGBTQ+ students should get that education; the whole class shouldn’t change for one student. Denkovich disagrees.

“[It’s like] taking 10 kids on a field trip, and only nine coming back,” Denkovich said. “A 90% success rate is great, but if your child is the one child left behind, it’s a problem for you and for that child.”

There’s no way to know who is LGBTQ+ unless there is space created for everyone to feel valued, respected and safe, they said, and even then there’s no standard timeline for coming out.

“The reality of being a queer student,” Irwin said, “is that you have to be the mature one that says, ‘Here’s who I am. Accept me.’”

“A natural reaction”

On the day The Reader talked to OPS teacher Lucas Martin, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, he was pretty sure a kid just came out to him as trans.

“They said their favorite colors [were] pink, blue and white, the colors of the trans flag. The way they were looking at me, I was like, ‘I got you,’” recalled Martin, who said the student was coming out of their shell for the first time. “I do [a lot of] coded language because as kids are discovering themselves, they don’t know how to articulate it, but they have someone they know [will get] it.”

An openly gay teacher who mentors many LGBTQ+ kids, he’s guided trans teens through dark moments.

“I’ve coached [a] student on how to come out as trans and not want to kill yourself as a 13-year-old,” Martin said. “[The potential for] suicide is very real.”

Suicide statistics for transgender youth are staggering; more than half of trans and nonbinary youth seriously considered committing suicide in the last year, according to the Trevor Project’s National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health 2021.

Emiliana Isabella Blanco, a local therapist who works with transgender youth and is herself transgender, says parental rejection has a major effect on a person’s mental health. According to the Trevor Project, trans and nonbinary youth whose pronouns are affirmed by everyone they live with attempt suicide at lower rates.

Like Sophie and Jamal’s parents, the parents of many of Blanco’s clients are supportive — but the kids nevertheless exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety. She said it’s hard to know whether they actually have diagnosable mental health conditions, or they’re responding to sustained alienation and abuse.

“[Sometimes it’s] just a natural human reaction to experiencing something that’s not only awful, but is ongoing,” she said.

That mental-health strain, Blanco said, can derail students’ academic careers. Blanco has seen trans kids flounder in school — neglect homework, show up late every day — and grapple with their bodies changing in ways that don’t affirm their gender.

“Instead of vilifying [them] and saying, ‘You didn’t do this homework, and you’re bad,’” she said, “[teachers should] check in and ask, ‘Everything OK, buddy?’”

Blanco said transgender youth of color face unique challenges as they battle both transphobia and racism — and, according to the Trevor Project, they’re less likely than their white peers to have access to mental health care. A Latina trans woman, she herself has dealt with people stereotyping her as a “fiery Latina” or “angry trans woman.” She’s also worked with Latinx kids who worry not only about gender-identity discrimination but also their parents being deported.

Many of Martin’s mentees are immigrants who struggle with poverty. The more marginalized identities his students have, he said, the more withdrawn and sad they seem. Meanwhile, Martin said, trans kids don’t always have transgender or queer teachers to serve as role models. Many trans and queer educators, he said, remain closeted, fearful of stigma and stereotypes about LGBTQ+ people as predators.

“The culture of [Omaha] is one of secrecy, where people are LGBTQ+ but don’t acknowledge it,” Martin said. “Students are trying to be themselves, and they see adults who are not.”

Martin strives to create an inclusive classroom where kids can be themselves. He displays pictures of his queer chosen family and stocks his bookshelves with literature that represents LGBTQ+ people. LGBTQ+ kids from other classes seek out his classroom as a safe space.

And when they’re in an accepting space, transgender youth can thrive.

Nothing Left to Prove

On the first day of class, Jamal Webber’s teacher misgendered them. Jamal told her, “I don’t use those pronouns anymore,” the teacher made the switch, and that was that.

“When someone misgenders me, I correct them, [and we move on] — that’s one of the best things I’ve ever seen,” Jamal said. “It’s nice to have [people’s] support … without [them] making a big deal out of it.”

According to her mom, Sophie gets tons of support at Millard. Sophie’s not out to her classmates yet, just to teachers and administrators. For now, Sophie and her mom like it that way.

“Her gender, her privates, that doesn’t matter,” her mother said. “Whether you’re friends with Sophie should be based on whether you get along with her.

Sophie’s mom knows things might not always be this easy.

“We’re not gonna run to public school and suddenly be free from the people who are against us,” she said, “because there sure as hell are going to be a bunch of people against [my daughter in the future].”

She also recognizes, however, that her daughter is becoming more secure in herself and how others perceive her. When Sophie first told her parents her gender, she wanted all things girly: frilly dresses, glitter, painted nails.

Not anymore. Now Sophie wears pants, shorts and a lot less pink than she used to. Her mother believes it’s because Sophie has made those around her understand what she’s known since she was a toddler. There’s nothing left to prove.

“Back then, she felt like she had to prove to the world how feminine she was,” she said. “Now that she’s been affirmed and she’s a girl, she doesn’t have to do any of that anymore. [Sophie] can just be who she wants to be.”

Special thanks to activist and public speaker Eli Rigatuso for offering his knowledge and input at the beginning of the research process for this story.

Leah Cates is a reporter and Editorial & Membership Associate for The Reader. You can connect with Leah via Twitter (@cates_leah) or email (leah@pioneermedia.me).