Although Legaspi remains overdue for a widespread revival, Owens did write a book about his underappreciated hero. The gorgeous, lushly illustrated, coffee-table hardcover, titled Legaspi: Larry Legaspi, the ’70s, and the Future of Fashion, was published in 2019, and it’s the closest thing to a biography of the designer that exists. It includes Legaspi’s own written account of his early life. He describes growing up in New Jersey, where he says his hard-drinking stepfather regularly beat his mother and molested him. After years of abuse and trauma, he left home for New York, where he opened a boutique called Moonstone and began designing garments. “I am self-taught,” he told the fashion journalist André Leon Talley in 1979. “I went to the Fashion Institute of Technology for a few semesters of basic trainings, but what you see is mostly my dreams.” In his own words, he was a “gay hippie” upon arriving in New York, but he soon gravitated toward the angular, intergalactic sparkle of glam rock. Incorporating elements such as arched collars and reflective materials into his designs, he also drew from the past—namely from the science fiction he had devoured as a kid.

Read: How Pierre Cardin’s futuristic fashion infiltrated everyday life

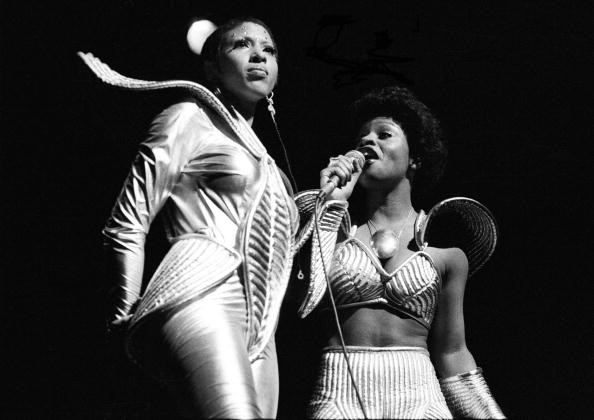

New York in the early ’70s was hardly what you would call restrained. But when Legaspi wore his own outfits on city sidewalks, his Flash Gordon–on–Fire Island style drew catcalls of “Moon man!” from passersby. “I never could bear to look like everyone else,” he told Us Magazine in 1980. Moonstone struggled to attract clientele at first, but that changed when Legaspi got a job on Broadway as a dresser for the original run of Jesus Christ Superstar. Soon, he was noticed by Labelle. The trio of Patti LaBelle, Nona Hendryx, and Sarah Dash was transitioning from a sweet vocal group—one that Legaspi had loved as a child—to a fierce and forward-thinking funk powerhouse. Legaspi began designing their stage costumes, stitching together shimmering metallics, white leather capes, and ludicrous plumage straight out of some hallucination of alien ornithology. Hendryx, also a lifelong sci-fi fan, had urged Legaspi, “Make me a spacesuit.” Labelle’s striking new look, the music magazine Melody Maker observed in 1974, was “like a soul version of UFO.”

Legaspi dubbed his new line of costumes “Primal Space,” a term that played on both his adoration of sci-fi imagery and his connection to the earthy pulse of funk and rock. His name began circulating, and as his Labelle creations made waves, other musicians took notice. Before long, the members of an unknown rock group playing small clubs in New York asked Legaspi to help them realize their own bizarre ideas for stagewear—costumes that were extravagant, gleaming, superhuman, and just a little bit scary. Legaspi obliged, unaware that Kiss would become one of the biggest bands of all time. “Our manager Bill Aucoin introduced us to Larry. He had a storefront in the far West Village,” the Kiss guitarist Paul Stanley recalls in Owens’s book. “He was doing costumes for Labelle.” In fact, Kiss stole Legaspi away from Labelle, whisking him up in a rise to fame that, ironically, did little to help the designer’s brand recognition. He loved applying his aesthetic to the world of popular music, and the money didn’t hurt. He wanted nothing more, though, than to be seen as a high-fashion creator.

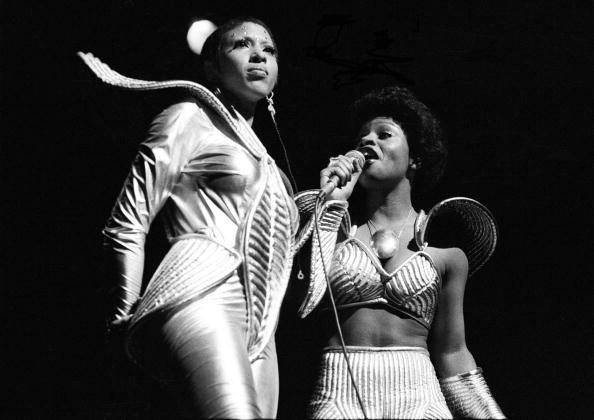

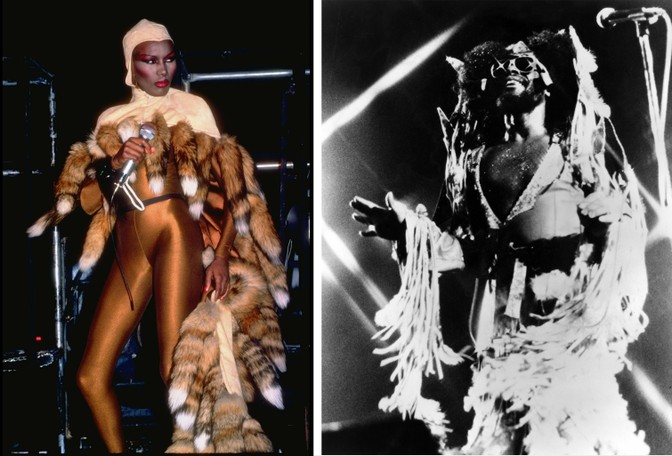

But Legaspi wound up stuck in a strange place: too bold to go mainstream and too weird to be embraced by the fashion industry. With seemingly nowhere else to turn, Legaspi continued making costumes for his friends in the New York art scene, including the operatic singer Klaus Nomi, whose retro-futurism meshed with Legaspi’s. And after becoming close friends with Divine, he supplied the gay icon with designs that accentuated camp, drama, and subversive sexuality. Grace Jones, as she was moving from modeling to music in the late ’70s, tapped Legaspi as well. But of all the people he dressed, no pairing was more perfect than Legaspi plus P-Funk. “I know the theater well,” Clinton told Vogue in 2018. “I watched a lot of these plays, and when we first did the Mothership Connection album in 1975, I knew that I had to get the costuming from Larry Legaspi.”