When I last met Jordan Peterson four years ago he was on the cusp of what some would call renown, others notoriety. Let’s settle for prominence. Peterson, a clinical psychologist, had spent the first three decades of his career in relative obscurity, teaching at the University of Toronto, churning out academic papers, maintaining a small private practice and producing YouTube videos on his interests in ethics, theology and myth.

All that changed in 2016 when he challenged, on free-speech grounds, a proposed Canadian law, C-16, which he argued would legally compel him to use transgender people’s preferred pronouns. (It became law in 2017.)

When I met him, he had recently appeared on Channel 4 being interviewed by Cathy Newman – a famously combative encounter on subjects including the gender pay gap, relations between men and women, and the rise of identity politics – that quickly went viral and has since had more than 38 million views on YouTube.

In the years since, Peterson has become the most visible, outspoken and certainly the most polarising figure in the ‘culture wars’ between Left and Right, challenging the new orthodoxies of political correctness that have permeated academia, education, and political and cultural life.

His book 12 Rules for Life: an Antidote to Chaos, has sold more than five million copies in English and been translated into 50 other languages. Through his talks, podcasts and videos – his own YouTube channel has five million subscribers – he has amassed a devoted army of followers, many proclaiming, dramatically, that he has saved their lives, bringing them back from the brink of depression, alienation and despair.

He has also galvanised an army of critics. Added to which, in 2020 he almost died after undergoing a prolonged and, to outward appearances, bizarre, treatment in which he was flown to Russia and put into a coma to free him from physical dependence on antidepressants, which was itself the culmination of a medley of ailments that boggle the imagination.

It has been a period that he readily describes as ‘insane’. Peterson, his wife and two children have lived in the same house in a quiet, residential area of Toronto near the university for the past 22 years. The last time I visited, we sat in a room hung with a picture of heroic Soviet soldiers in the midst of a battle and a monumental painting of Lenin proclaiming Soviet authority at the Winter Palace in 1917.

Among his areas of interest is the psychology of authoritarian states, notably Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. The paintings, he explained, were an aide-memoire of the iniquities of totalitarianism and the evil of art being subordinated to propaganda. He particularly relished the irony of having bought them for a song on eBay: ‘The most capitalist platform that’s ever been invented!’

But in recent times the house has been refurbished and the paintings put in storage. ‘They got a bit depressing,’ his wife Tammy tells me. This time we speak in an upstairs room, filled with First Nation carvings, masks and totem objects.

Peterson is an honorary member of the Kwakwaka’wakw – a Pacific Northwest Coast indigenous people. The carvings are by his friend, a master craftsman called Charles Joseph. They are so large that scaffolding had to be erected at the side of the house in order to winch them into the room. Peterson is a complicated man.

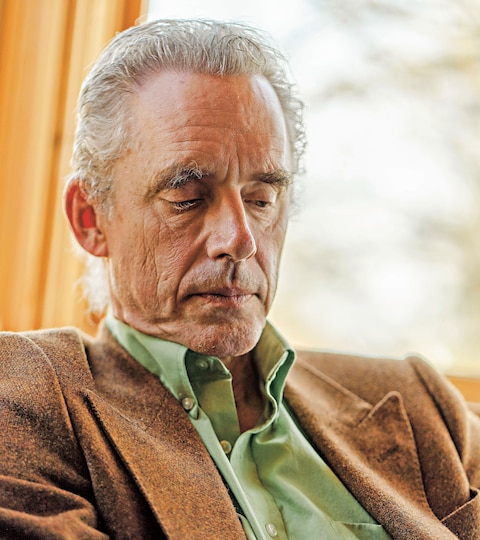

He is 60, medium height, craggy-looking. He has lost weight since his illness; his features are drawn. His default posture is a kind of coiled thoughtfulness, as if the motors of some sort of intellectual inner struggle are in perpetual motion. His manner can be adversarial, his attention to detail forensic. Somebody once described arguing with him as like ‘throwing stones at a tank’.

Watch him being interviewed on YouTube and you can get the sense that he is inwardly marking the other person’s arguments for coherence, logic and semantic exactitude. He is prone to a certain fervour in his pronouncements, and has a tendency towards the apocalyptic. ‘That’s hell,’ he says at various times in our conversation, speaking, one senses, literally.

Credit: Ian Patterson

‘Hell’ is how he describes the illness that plagued him for two years; and ‘hell’, he says, is where he confidently believes Michel Foucault, the French intellectual who is one of his bêtes noire, now resides. Foucault was one of the two French ‘deconstructionist’ philosophers – the other being Jacques Derrida – whose ‘postmodern and neo-Marxist theories’ Peterson says now threaten not only free speech but the very foundations of Western democracy.

Derrida was ‘a trickster’, Peterson says, but he reserves a special contempt for Foucault, ‘so smart, so brilliant, but utterly corrupt ethically’. Last year, a fellow intellectual, Guy Sorman, raised a storm in France by claiming that, while living in Tunisia in the 1960s, Foucault sexually abused young boys in a local graveyard.

‘At that point,’ Peterson says, ‘you’re a denizen of hell.’

There are two distinct sides to Peterson. One side is his political pronouncements, which have put him in the front line of the culture wars and which tend to excite the attention and opprobrium of his critics and the media. The other side is his theories on how to lead an ethical and productive life, which are what attract his millions of readers to buy his books and listen to his talks.

Many of them are young men, who credit Peterson’s advice to ‘Stand up straight with your shoulders back’, ‘Tell the truth – or at least don’t lie’ (and – more oddly – ‘Pet a cat when you encounter one on the street’), but above all to stop seeing yourself as a victim and take responsibility for your actions, as having transformed their lives.

His new book, Beyond Order: 12 More Rules For Life, deals primarily with the need to achieve a balance between the creative, anarchic spirit and the organising principle. It includes such advice as: ‘Do not carelessly denigrate social institutions’, ‘Imagine who you could be, and then aim single-mindedly at that’ and ‘Be grateful in spite of your suffering’.

It is notably uncontentious on any political issue, yet its very existence apparently proved so distressing to some staff at his Canadian publisher, Penguin, that there were reports of people crying in meetings at the prospect of the book being published. Responding to this, Peterson’s daughter Mikhaila tweeted: ‘How to improve business in 2 steps: Step 1: identify crying adults. Step 2: fire.’

Earlier this year, Peterson made a series of appearances in theatres and other venues in the US and Canada, at which he says he talked to 150,000 people. ‘All of the people who come to the tour are there because they’re trying to improve,’ he says. ‘I hardly ever talk about political topics. Every single person is there because they’ve decided they’re going to aim up. And it’s not intellectually pretentious.

‘A lot of people have attacked me for that – I’m the stupid person’s smart person. But you know, I’m not so upset about that definition. What are they? The smart person’s smart person? And I thought you weren’t elitist. Part of the role of an intellectual is to articulate what people know but can’t say. In that sense, I’m doing my job.’

Peterson’s first brush with controversy came in 2016 in the debate over C-16, which ruled that ‘refusing to refer to a transperson by their chosen name and a personal pronoun that matches their gender identity’ in a workplace or a school, would be considered discrimination.

Peterson argued that at no time in British common law history has the legal code mandated what people must say, as opposed to simply what they must not say. (Although he added that he would use the gender-neutral pronoun of a particular person, if they asked him to.) This, he said, was not about gender, but about free speech – a principle that he was prepared to go to jail for. Peterson did not go to jail. But the rise of gender politics and the proliferation of ever more letters among what he calls ‘the alphabet people’ (LGBTQIA) have remained a source of consternation and exasperation.

What is most striking about the rapidly increasing numbers of teenagers and young adults self-identifying as trans, ‘non-binary’ or ‘queer’ is that whereas it was once young men who were in the majority, it is now increasingly female adolescents.

‘I knew when all this nonsense started back in 2016 with C-16, you dumb bastards are going to start a psychogenic epidemic,’ Peterson says heatedly. (Psychogenic meaning mental or emotional conflict). ‘And that’s exactly what happened with this rapid onset of gender dysphoria. For every kid you save, you will doom a hundred.’

Peterson debating the C-16 law at the University of Toronto in 2016

Credit: Getty Images

One argument holds that in an earlier age the small number of people exhibiting gender dysphoria were inhibited by social or cultural constraints, but now feel more free to fully express themselves.

‘Well, that’s what the claim is,’ Peterson says. Some men have a female personality structure, and some women a male personality structure. ‘So the idea that there is fluidity and there is overlap in gender personality is true. What isn’t true is that this means you’re in the wrong body, and that’s not true even a bit.

‘But the radical types’ notion of gender is completely empty. “Gender is what you feel”. OK, what do you mean by “feel”? “I feel like I’m a man.” Well, how do you know, because you aren’t. Do you always feel that? “Well, sometimes I do, and sometimes I don’t. So I’m fluid.” It’s so juvenile and narcissistic that it’s almost impossible to exaggerate.

‘There’s a lot of confused people, and there’s certainly a lot of confused adolescents who could be enticed into narcissistic abnormality as a consequence of attention-seeking. No problem, man. Ten per cent of adolescents will line up for that, especially girls because they’re prone to psychogenic epidemics. But what’s happening now is that gay kids are being convinced they’re transsexual. Well that’s not so good for gay people, is it?

‘I’ve had people come to me who have uncertainty about their sexual identities. The right way to handle that therapeutically is to say, “OK, I don’t know what the hell is best for you, and clearly you don’t either because you’re confused. So let’s evaluate the whole range of possibilities before we do anything precipitous, let alone surgical.” It’s like sacrificing children to Moloch. It’s horrible, what’s happening.’

Peterson grew up in the prairie town of Fairview in Northern Alberta, where his father was a teacher. At university he studied political science before switching to clinical psychology. He went on to teach at Harvard before moving to Toronto in 1998.

Credit: Ian Patterson

As a young man, Peterson had been obsessed with the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation. In 1999 he published Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief – a 600-page work, 14 years in the writing, bringing together neuro-psychology, cognitive science, biblical study and Jungian approaches to mythology and narrative.

Underpinning it all was an attempt to get to grips with the roots of the ideological thinking that had given birth to Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, leading to a conviction that he repeats often: ‘Abandon ideology’. He quotes Carl Jung, a hero: ‘People don’t have ideas; ideas have people.’

‘I was dealing with what I thought was the cardinal problem of the age, the motivation for atrocity in the service of belief,’ he says. ‘I thought, these are fundamental ideas and they’re going to change everything.’

Life was good. The courses he taught at university were popular. ‘Ninety per cent of the kids, when they wrote the evaluations, would say, “This course changed the way I thought about everything.”’

His clinical practice was successful. He had a modest public presence through putting his lectures on YouTube and occasionally appearing on local television. It was a life, he says, ‘within the bounds of comprehensible normality, comfortable and exciting at the same time. I was very satisfied with my family, my career was going great; I had a good relationship with all my graduate students. I liked it a lot.’

Then the clouds rolled in. Depression runs in the family. His father and grandfather were both severely affected, he says. He inherited that predisposition and it manifested itself when he was young and multiple times through his life – a feeling he described to me as ‘like freezing to death on an endless stark plain knowing that the reason that you got there is because you did everything wrong’.

In 2016 it returned with a vengeance. As a result of the growing controversy over his pronouncements on the question of C-16, his university job was under threat. He was under fire from The College of Psychologists, accused of ‘not keeping email contact with clients in proper order’ in the few months following his emergence into notoriety, and being investigated by the tax authorities.

‘They admitted they made a mistake, which was real nice of them,’ he says drily.

At the same time other health issues began to multiply, exacerbated by the stress of his public profile and the frenetic round of lecture tours and media appearances.

Since early childhood, Peterson’s daughter Mikhaila had suffered from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, which necessitated a hip and ankle replacement at 17. She also suffered from chronic fatigue and depression. Experimenting with her diet, she began eliminating certain foods, finally adopting what she calls ‘the lion diet’, which consists solely of ruminant meat (beef and lamb), salt and water, and which she claims put her multiple disorders into remission.

In search of a remedy to his own bouts of depression, Peterson followed her example, subsisting on a diet solely of steak (‘it’s boring’, he admits), as well as being on a mild regimen of antidepressants.

In 2019, his wife Tammy was diagnosed with a rare kidney cancer, which doctors told her was terminal. (After two extensive surgeries, she survived.) Devastated by his wife’s diagnosis, Peterson’s health worsened and he withdrew from public life completely.

Suffering from an autoimmune disorder, extreme anxiety and severe depression, doctors increased his prescription of the sedative benzodiazepine. Several failed attempts to detox in American hospitals left him with a condition called akathisia, where the patient constantly feels on the border of panic and is unable to sit still.

In desperation, his family flew him to Moscow, for an emergency detox treatment that involved being placed in an induced coma for eight days. It was merely the beginning of a protracted journey from Moscow, to Florida, to another hospital in Belgrade, before finally returning to Toronto and more or less normal life.

What, I ask, is the single most important thing he learned from his illness?

‘That there are things worse than death.

‘I was in so much pain I thought I might throw myself through a window. It was just agonising. Unbelievable pain. And it was so perverse, because at the same time this was happening, an immense world of possibility was opening itself up to me – and yet I’m so immobilised, I can’t think, I can’t work, I can’t do anything.’

He felt, he says, ‘like Tantalus’, the character from Greek mythology, whom the Gods put on the shore of a beautiful stream, under a tree bearing the most luscious of fruit above him, but when he holds his cup out to drink from the stream, the stream recedes, and when he reaches to take a fruit the branch moves away.

‘I thought, that’s my life, man. And I thought, this has been going on for two years, I can’t live like this for 20 more years. But what really bothered me was watching the effect of my illness on the people around me, how much pain it was causing them.’

Credit: Ian Patterson

Peterson is an emotional man and as he says this something seems to catch in his throat as if he may cry. Talking of the tumultuous upheavals in his life over the past four years, he tells me he had recently been speaking with his parents, brother and sister on one of their monthly Zoom catch-ups.

‘There was a bit of contention during the talk. My brother said, “We don’t know what to do with you, we don’t know what to say, because there’s two of you. There’s the person we knew, and there’s whoever the hell you are now, and it’s hard for us to adapt to that.” They don’t know who the hell I am.’

And does he know, I ask?

He pauses for what seems an age. ‘No, I don’t,’ he says at last. ‘I’m trying to figure that out along the way.’

His reputation, he says, puts him in the enviable position of being able to engage intellectually with almost anyone he chooses. ‘That’s pretty weird, but it’s as exciting as hell for my podcast for someone as curious as me. I talk to Frans de Waal, he’s the world’s greatest primatologist. And that’s unbelievably exciting.’

Then there are the encounters he has on his book tours, which he says are ‘overwhelming. People come up to me on the street and they tell me things that you would probably only hear from someone you knew closely once in your life. And that happens all the time.

‘Someone will relate some very personal story of transformation, their relationship with their father, or how they fixed up their family… All the encounters are unbelievably positive; they’re not just positive – they’re too positive.’ He shakes his head, and there is that catch in his voice again.

One of the remarkable things about Peterson is not just the degree of admiration – one could almost say adoration – he inspires among those who read his books, download his videos and attend his speaking tours, but the measure of vitriol he stirs in his critics. Over the years he has been a frequent user of Twitter, promoting his lectures on such subjects as the psychology of creativity, but also to post acerbic views on politics and the culture wars – to the frequent fury of the Twitter mob.

Health and family problems led to a withdrawal from public life in 2019

Credit: Getty Images

Shortly after our meeting, he announced he was leaving the platform, declaring, ‘Twitter is maddening us all.’ A day earlier he had posted a picture of plus-size model Yumi Nu on the cover of the Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit edition with the caption: ‘Sorry. Not beautiful. And no amount of authoritarian tolerance is going to change that.’ The tweet, not surprisingly, provoked an avalanche of criticism, even from his supporters.

When I contacted him via email he replied that the tweet ‘was not a mistake, nor was it the reason I left Twitter. The use of that model, who was not athletic (remember: SPORTS Illustrated) was manipulative economically and in relation to the model herself (although she participated in her own exploitation). Beauty is an ideal. Almost all of us fall short of an ideal. I am not willing to sacrifice any ideal to faux compassion. Period. And certainly not the ideal of athletic beauty.’

He had left Twitter, he went on ‘because it’s an irredeemable snake pit’ and henceforth he would only post sporadically through a member of his staff. ‘I don’t have access to my account otherwise. This stops me from reading comments from anonymous trolls and helps me keep my temper.’

Peterson has been attacked and vilified as a misogynist, an Islamophobe, a white supremacist and a transphobe – often, it can seem, by people who have read about him rather than having actually read or listened to anything he has said.

‘I was “anti-semitic” and “a Jewish shill” at the same time – that was fun. But one of the things that’s protected me is that I’m not the person the radical Left would like me to be.’

Does he care what people think of him?

‘Oh yes, for sure. You’d have to be…’ He checks himself, ‘No, you are crazy if you don’t care what people think about you. Part of the way you keep yourself sane is seeing your impact on other people, which is partly why it’s helpful to say “be married and have friends” because they tell you when you’re acceptable, and acceptable kind of means being sane.

‘And that’s partly also what makes me conservative; I realised how much of our individuality is dependent on our properly investing within the social sphere. It’s crucial. All of that keeps you sane. And then I look at the impact of my thoughts on people and what I’ve said, and as far as I can tell, apart from the people who dislike me, even though they never pay attention to what I’m actually saying, all of the consequences seem to be positive. And I never have negative encounters with someone publicly.’ He thinks about this. ‘Actually, that’s not true – I was once bothered by a drunk woman in Dublin.’

Peterson takes a break to be photographed, I wander downstairs. Tammy is putting out some recycling. She and Peterson grew up on the same street in Alberta and were childhood sweethearts. They have been married for 33 years.

Peterson’s life currently is ‘quite a challenge’, according to Tammy, his wife of 33 years

Credit: Ian Patterson

I tell her what he’d said about his family finding it difficult to relate to him now, and his reply when I asked if he knew who he was.

She smiles. It had been ‘quite a challenge’, she says, for her husband to deal with the radical changes in his life. ‘He’s no longer a professor; he’s no longer a clinical psychologist. A lot of things that he thought of as how he was were taken from him. Our marriage surviving was a real blessing for both of us, because that at least has been stable through all this time.’

Between their illnesses and Covid, she says, they were mostly apart for two years. ‘It was very interesting when we got back together. We’d been through so much and learnt so many different things, we didn’t have a lot in common.’

From the time their children were born they had a practice of ‘dating’ twice a week. ‘You can’t answer the phone, you can’t answer the door, you can’t do any email, you can’t bring up any issues. You just have to be together. We did that for the last 32 years. So when we were in the house together after all this, twiddling our thumbs and thinking, “Well, here we are”, I said, why don’t we have a date? Jordan would get the room ready, make sure there were candles lit and put on some music and we’d dance.’ For dinner he’d eat his steak, and she’d eat the only thing in her diet – lamb. ‘I think it saved my life.’ They’d toast each other with sparkling water.

The photographer finishes and a friend arrives for dinner, but Peterson gestures for me to take a seat. He has been thinking more about that question, who does he think he is?

Somebody had once asked him, he says, how he would like to be remembered, ‘whatever that means. I would say, as an encouraging voice and doing my best to tell the truth.’

In 1983, he says, he was experiencing ‘a crisis of meaning. And I thought then, I’m going to do my best not to say anything I don’t believe to be true. So at least I can stop lying. And I’ve been practising that as diligently as I can. Some German philosopher – he was a sociologist – criticised me, saying, “What role is Peterson playing?” I thought, I don’t know if it’s ever occurred to you, but not everyone is playing a role.

‘In this interview, for example, I’m not thinking I want to portray myself as a reasonable person, who would appeal to people on the Left and dispel, what would you say, some of the misconceptions about me, and sell more books. I don’t know if I want any of that. But I do know I can say what I think.’

He pauses. ‘I learned, partly from reading great clinicians, that the speech that promotes physical, psychological and social health was truthful speech, and also that that was an adventure, because if you’re saying what you believe to be true then it’s you that’s having the adventure. That’s the idea, isn’t it? The truth will set you free. And that’s a hell of a thing – to be free.’