For the past decade there’s been a plethora of LGBTQ memoirs published every year. As the Baby Boomer generation, who matured right before and after the Stonewall Riots, have entered their sixties and seventies, they want to bear testimony both on how they impacted gay liberation movements and how that drive towards equality affected their own lives. These voices are vital for preserving a historical record on this activism that literally reshaped American acceptance of, alternative sexualities.

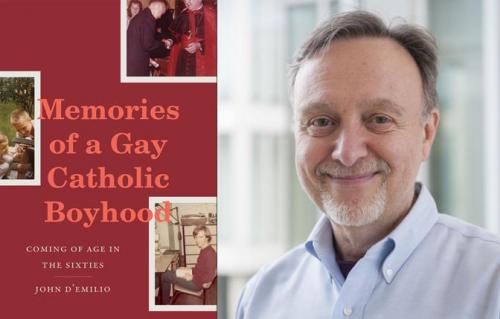

Therefore, it is fitting that John D’Emilio, one of the preeminent queer historians instrumental in helping establish Gay and Lesbian Studies as an academic discipline, has written a memoir, “Memories of a Gay Catholic Boyhood,” detailing his coming of age in the sixties through the beginning of his graduate career at Columbia University, right after Stonewall.

D’Emilio is Professor Emeritus Gender and Women’s Studies at University of Illinois-Chicago. His 1984 book “Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970,” is considered foundational, while his research with co-author Estelle Freedman, “Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America,” was cited by Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy in the Lawrence vs. Texas decision that overturned sodomy state laws. Finally, he wrote “Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin,” an essential biography on the black gay civil rights icon.

In his preface, D’Emilio sets the goal of his book: “How did so many young people move from the quiet of their family backgrounds to the social and political upheavals of this seemingly un-orthodox era? What kinds of experiences provoked their shift in outlook? How did they become agents of change? And how did their lives change because of this?”

He largely succeeds in showing how Baby Boomers moved from the status quo life of the fifties into a new world of activism, dissent, and nonconformity, which in his case consisted primarily of political radicalism by protesting the Vietnam War and participating in the emerging gay sexual revolution.

D’Emilio constructs his memoir like a three-act play. Act One delves into his Italian family boyhood in the Bronx and early Catholic education at St. Raymond’s school. Act Two explores his formative high school education at the Jesuit St. Regis school. Act Three centers on his undergraduate life at Columbia University including campus protests as well as exploring gay life in Greenwich Village.

D’Emilio mentions the inspiration for his book came preparing for and recovering from triple-bypass heart surgery, recalling memories from his youth but also wanting to inspire young people in the age of Trump to become progressive activists, just as his generation had done. He kept letters written during his Columbia days to his high school friends describing his antiwar activities as well as his emerging gay identity.

Faith, family, forensics

Family stories told at the dinner table reinforced his Sicilian ancestry, while his mother’s photo albums helped him reconstruct childhood memories. There are no skeletons in the closet here, just an affectionate, close-knit, multigenerational, republican Catholic family. His parents were working-class Italian immigrants, living in a housing project called Parkchester that was private rent-controlled housing but also a model community. D’Emilio is adept at painting the classic post-war urban life where his father made enough money so they could live a solid middle-class existence. His mother decided early on that education was destiny for the smart D’Emilio.

His religious faith became central, leading to his acceptance at the prestigious elite all-male Jesuit St. Regis high school (after acing a competitive entrance exam) where he blossomed, developing friendships outside his neighborhood. He excelled in Latin and Greek. The school exposed him to more liberal thinking, but primarily taught him to think for himself.

Recruited for the Speech and Debate Society, he toured the country, entering and winning debate tournaments, brilliant at public speaking. He was obsessive in researching background material for these contests and studying 4 hours a night. So dedicated, he opted to attend a Georgetown tournament as opposed to going to his beloved grandmother’s funeral.

During this time he was becoming more aware of his attraction to men and would play footsies and body grinding on crowded subways with handsome older men. In his sophomore year, a teacher suggested he read James Baldwin’s “Another Country” and he realized there were other gay men like him. He began having sex with strangers in subway bathrooms and park bushes, the ways gay men often interacted with each other in the early 1960s.

However, D’Emilio’s Catholicism compelled him to confess his “sins” and resolve to abstain from any further sexual activity. He even contemplated in his senior year becoming a priest and applied to a Jesuit seminary, but later decided he had to deal first with accepting his gayness, otherwise he’d be fooling himself and his superiors.

At Columbia he’s exposed to new people who don’t believe in God, which shook his faith in the institutional Church. He also had to confront his views on the Vietnam War especially since de- ferments to students were ending. Much to the consternation of his parents, he wanted to declare himself a conscientious objector, though his failure to pass the army physical finally saved him.

Still as he gets involved in Vietnam War protests, he admires the priests and nuns’ activism and decides he still believes in some Catholic teachings on social justice and pacifism.

During this stage he will read Oscar Wilde’s “De Profundis,” his paen to love and an apologia for his sexuality, written while imprisoned for gross indecency. “The real fool is he who does not know himself. To speak the truth is a painful thing. To be forced to tell lies is much worse. To aspire to a Christlike life, one must be entirely and absolutely oneself.”

The book enabled D’Emilio to embrace his sexual desires while still living out the ethics he had so deeply internalized in his Catholic upbringing. He’s able to come out for the first time to high school friends now attending seminary. The book chronicles gay life at the end of the 60s with signposts like Christopher Street, the Oscar Wilde Bookshop, and visiting the Stonewall Inn prior to the riots. He decides to study American history at Columbia, but from nontraditional vantage points such as race, gender, and sexuality, for his graduate program.

What is so refreshing about the book is D’Emilio’s non-judgmentalism. Even though he ultimately rejects institutional Catholicism, he understands how it has formed his values and made him a better person. He learns to trust his own instincts and not be dependent on others’ demands upon him. This account of his coming-of-age journey is warm, affectionate, insightful, and compulsively readable, as one feels transported into a more carefree, less ambiguous time.

Reportedly, D’Emilio is writing a second volume covering his LGBTQ activism from the 1970s through the 1990s, which readers will eagerly anticipate after finishing this first installment.

Although D’Emilio charts his particular transformation from conformity to radicalism through the prism of his sexuality, it is written so honestly and universally, anyone, whose personal discoveries collide with their cultural values, causing tension leading to growth, will glean wisdom, assisting them as they seek their own path in exciting unexpected new directions.

‘Memories of a Gay Catholic Boyhood: Coming of Age in the Sixties’ by John D’Emilio. Duke University Press, $29.95 https://www.dukeupress.edu/

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.