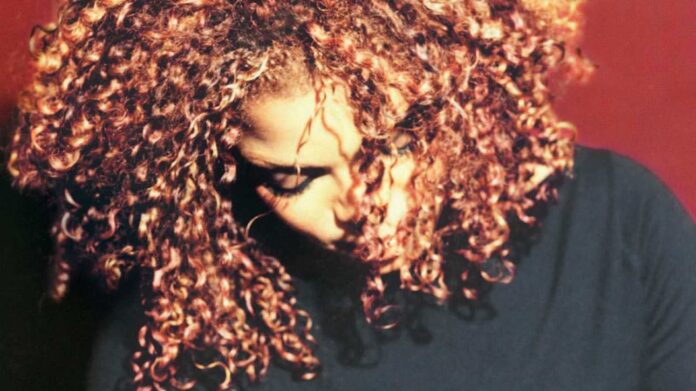

In the liner notes for her 1997 album, The Velvet Rope, Janet Jackson pays tribute to her fallen friends, writing, “I dedicate the song ‘Together Again’ to the friends I’ve lost to AIDS, Dominic, George, Derrick, Bobby, Dominic, Victor, José … I miss you, and we will be together again.” “Together Again” was the emotional anthem to her loved ones who perished from AIDS, but instead of choosing to pay homage with a beautiful ballad, she decided to honor her friends by writing a disco anthem. “Together Again” would not only commemorate her dear friendships, but it would do so by celebrating their lives in the most respectful way possible: by turning their eulogy into a classic dance song. By evoking disco and queer dance culture, Jackson subverted her pop grief by turning it into pop joy.

When talking about “Together Again”, Jackson said, “It was a lot of fun to write, and it brought back a lot of memories. I wrote that for all my friends who have passed away from AIDS. I may have seven, eight friends who have died of AIDS, and the song reflects their personality, the energy they had. It’s rejoiceful; it’s rejoicing.” She credits the song with making her aware of her devoted queer following, a following she fully embraced on The Velvet Rope, which would be Jackson’s first record that would speak frankly of the queer influence in her music.

Though the record’s brutal honesty and emotional candor would be justly celebrated, and Jackson was decidedly forthright about her struggles with depression and spousal abuse, issues that led to her creating The Velvet Rope, one aspect of the record that deserves special attention is her unabashed acknowledgment of her work’s importance in queer culture. So much of The Velvet Rope is dark and introspective that the queer moments laced throughout the tracks provide a much-needed lift.

“Together Again” was one of six singles released from the album and became one of Janet Jackson’s greatest hits. It’s an exuberant song that recalls Donna Summer, Diana Ross, and Gloria Gaynor at their giddiest, and it belies the tension and struggle that cloaks most of The Velvet Rope. Jackson shared details of the depths of her depression, admitting that she struggled to get out of bed. The album’s darker, more contemplative tone made it a somewhat harder sell for her audiences, many of whom were caught off guard by the moodiness of the record. Though it would debut at number one on the Billboard album charts and ultimately sell over 8 million copies worldwide, it was decidedly a more niche project for the pop diva.

With The Velvet Rope, Jackson’s work was starting to be compared to confessional singer-songwriters from the 1970s, including her idol, Joni Mitchell (who appears on the first single, “Got ’til It’s Gone). Mitchell’s emotionally naked Blue was cited in more than a few magazine articlesreviewing The Velvet Rope. Dance-pop artists were supposed to create escapist and fun music, and just as she did with her fourth album, 1989’s Rhythm Nation 1814, Jackson brought weightier concepts and themes to the dance floor and pop radio.

Former players with The Time and star graduates from the Minneapolis Sound, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, had worked with Jackson since 1986’s breakout album, Control. Marrying her soft pop instincts with their innovative synth-funk, the trio would become one of the most reliable collaborators in pop music. Though Jackson is the creative force behind The Velvet Rope, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis provided the singer with musical support and armature on which she could hang her musings and thoughts.

By the time they joined Jackson for The Velvet Rope, they were fellow legends and icons in their own right, working for some of her peers and becoming the most in-demand urban-pop and dance-pop producers. Their work with other artists was impeccable – listen to the gems they’ve crafted for New Edition or Boyz II Men – but they shared unique chemistry with Jackson that often overshadowed their other work.

As they did with Rhythm Nation, Jam & Lewis were able to work with Jackson on creating mainstream dance-pop that would address complex themes. In the case of The Velvet Rope, the trio would again mine Jackson’s personal life and set her insecurities, anger, resentment, and sorrow to a pop beat. But it wasn’t just the sadder songs that made The Velvet Rope special. It was the gayer ones.

The Velvet Rope would contain references and allusions to queer culture and tracks that were openly queer. Aside from “Together Again”, Jackson recorded “Free Xone”, a sharp and blustery funk jam that decried homophobia; she also did a rare cover, this time of Rod Stewart‘s “Tonight’s the Night”, except she chose to maintain the female pronouns, turning the tune into a carnal, same-sex love song. Not only does she choose to sing about queerness on the record, but she and Jam & Lewis insert nuggets of queer culture, like having Jackson and her friends bray the “But ya’ are Blanche, ya’ are!” catchphrase from the camp horror classic Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? or by slyly slipping in a sample of Diana Ross’ disco anthem “Love Hangover” on the track, “My Need”. These loving and intimate references are “for the kids”, a term of endearment Jackson uses when describing her gay fans or gay family circle.

Though it seems somewhat unremarkable in 2022 for a mainstream pop artist to embrace queerness, in 1997, the cultural landscape was quite different. Though it was far better than the repressive 1980s, which saw the looming shadow of the Reagan Administration as well as the scourge of the AIDS crisis, queerness was still a divisive topic. The reprehensible Defense of Marriage Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton a year earlier. Just three years earlier, the Clinton administration instituted the discriminatory “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

The prevailing attitudes of the political landscape also trickled their way down into pop culture. Even though the 1990s saw a bright burst of out-and-proud pop stars like k.d. lang, Melissa Etheridge, Elton John, and RuPaul; television celebrated Ellen DeGeneres’ much-ballyhooed coming out on her sitcom, Ellen, in April of 1997, just a few months later ABC slapped warning labels on episodes that dealt with queerness.

So even if there was far more representation and acceptance, there was still a significant risk for a mainstream pop star to embrace her queer following and play with identity herself. Like many celebrities, Jackson was also the subject of rumors about sexuality. She rarely denied these claims, arguing that doing so would imply something shameful about queerness. But with the songs on The Velvet Rope, Jackson explores sexual identities freely, seemingly unconcerned about fuelling questions.

Celebrities take to social media to claim fluid gender and sexual identities, insisting that labels are restricting and reductive. This freedom from concern makes “Tonight’s the Night” such a thrilling moment on The Velvet Rope. Jam & Lewis create a breezy, relaxed soundscape for Jackson to coo seductively to her lover, asking that she “loosen off that pretty French gown,” before she promises that “Tonight’s the night / It’s gonna be alright / ’Cuz I love you girl.”

There’s an intimacy on the record – Jackson’s whispered vocals with their amplified catches of breath and sighs – and the ‘revelation’ of Jackson singing erotically to a woman isn’t a revelation at all. Instead, we’re led gradually and subtly to the act, like the lover in the song. Though some critics were confused by Jackson’s cover: The Daily Telegraph’s Neil McCormick’s oddly called it ‘bizarre’ while AllMusic writer Stephen Thomas Erlewine opined that the song felt ‘forced’. But these takes miss the point: Jackson could have done some crass queerbaiting, particularly if she couched it in the more explicit or explosive numbers, as she had done with the songs dealing with sexual fantasies (including S&M and bondage); however, she chose to tell this particular story in a sun-dappled, gentle pop ballad. The simplicity of “Tonight’s the Night” reveals its verisimilitude.

As lilting and wistful as “Tonight’s the Night” is, “Free Xone” is a loud, cacophonous workout of drums, horns, and explosive vocals. Jackson’s small voice practically purrs on the track – the late 1960s/1970s pastiche built on samples from soul numbers of that decade: Pleasure’s 1977 song “Joyous”, Lyn Collins’ 1972 track “Think (About It)”, Archie Bell & the Drells’ exciting “Tighten Up” (1968), and Stevie Wonder’s 1973 tune “Don’t You Worry ‘bout a Thing”. Jam & Lewis use those samples adroitly as they draw in other sounds from 1970s R&B and funk, creating an exhilarating moment on the record that jolts listeners.

The lyrics are deceptively straightforward: it’s a protest song but one in which Jackson shows contempt for homophobia by cleverly rewriting the “Boy Meets Girl” narrative by positing different permutations of that scenario that are inclusive of queer sexualities. The recurrent theme in the song is freedom, as the sampled voice demands listeners to “Let’s get free!” Jackson sets out her utopic manifesto, which is boiled down to: “Free to be who you really are / One rule / No rules / One Love / Free zone.” As with the disco anthem of “Together Again”, Jackson and her collaborators didn’t impart their message with earnest pop balladeering – which would be predictable and expected – but chose to do their social justice work on the dance floor.

With The Velvet Rope, Jackson solidified her status as a gay icon. The album was feted in the gay press, and it won the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Music. In 2008, the organization again honored her with its Vanguard Award for her continued gay rights advocacy. Though she would be a consistent ally of the queer community – she would record the icy Euro-disco song “Rock with U” with her gay fans in mind in 2008 – The Velvet Rope represented the peak of her gay allegiance in her artwork. After the dark and emotional Velvet Rope, Jackson made a return of sorts to sunny pop with the upbeat All for You, which represented a move away from the expressive and ambitious work of its predecessor.

All for You was predictably another massive seller for the singer, and it unfurled another string of hit singles before she traversed the new millennium with new career challenges. Her work after The Velvet Rope was consistent as she weathered stark changes in the music industry as well as changes in pop trends. Her follow-up albums to The Velvet Rope each had bright moments and her 2015 LP, Unbreakable, was arguable her most consistent set since the mid-1990s, but The Velvet Rope is arguably her masterpiece. And one in which she brilliantly welcomes her queer audience.