On September 22, 1975, President Gerald Ford attended the World Affairs Council at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. As he exited, Sara Jane Moore pulled a .38 revolver and shot at Ford.

She missed, thanks to the swift actions of former Marine Corps veteran Oliver “Billy” Sipple, a San Francisco native who happened to be in the crowd and thwarted the assassination attempt. An often-overlooked slice of history, it was a gay patriot who saved the president’s life.

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay up-to-date with the latest LGBTQ news

President Richard Nixon was sometimes perceived as gay because of “that funny, uncoordinated way he moves,” according to staffers close to him.

Ronald Reagan and his advisors were concerned that the public might regard him as gay due to his career as a Hollywood actor. He was also embroiled in scandal on the eve of the 1980 Republican National Convention, which inferred that Reagan was being controlled by a right-wing gay network, manipulating him as a Manchurian-like candidate. There was no evidence to support these claims, and his administration employed more gay individuals (usually closeted) than any other in previous presidential history.

“Ronald Reagan and his advisors were concerned that the public might regard him as gay due to his career as a Hollywood actor.” — James Kirchick

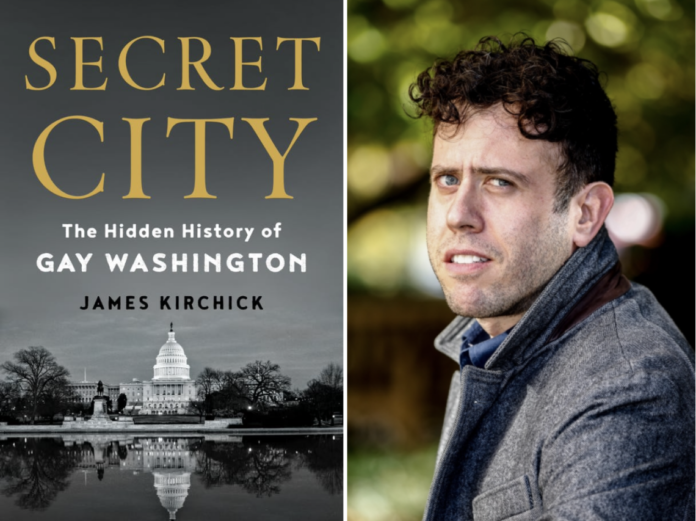

These reminders and revelations are a mere thumbnail of scenarios explored in James Kirchick’s book Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (2022). In it, he presents a detailed retrospective of gay individuals who walked the nation’s highest political corridors, working for and with government agencies while keeping their own lives hidden.

Secret City is not just perhaps the most richly detailed look at gay life in the nation’s capital to date. It may also be the most debated. Alexandra Jacobs in the New York Times praised the work as a “sprawling and enthralling history” and a “luxurious, slow-rolling Cadillac of a book.” Meanwhile, in The Washington Post, Matthew L. Riemer wrote that “Kirchick seems content not to ask questions about those waiting outside.”

For his part, Kirchick is well aware of the omissions in his reporting but says that the hard truth is that until very recently, these government institutions have long been governed by white men. Women, minorities, openly gay and/or trans individuals were completely overlooked and had little to no sway in political circles.

A Yale graduate who describes himself politically as a centrist, Kirchick elaborated on his political leanings and research, telling LGBTQ Nation that he “voted for Joe Biden in 2020 and for Hillary Clinton in 2016… I’ve written so many things on various topics. It shouldn’t be hard to define what my political views are on various issues.”

Regardless of ideology, these are tough times to be a politically aware queer person. But despite the attacks on queer equality in red state legislatures and a looming presidential campaign by Donald Trump, Kirchick implies that the worst may be behind us.

Writing for the Atlantic in 2019 on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, Kirchick suggested that “For the gay movement to persist in its current mode risks prolonging a culture war that no longer needs to be fought because one side — the gay side — has already prevailed.”

Kirchick further wrote, “Across wide swaths of the planet, homosexuality itself — or even the advocacy of equal rights — is criminalized, and societal acceptance lags far behind that found in the liberal democratic West.”

But recent events have proven otherwise, including nearly a dozen anti-LGBTQ laws that went into effect July 1 across the U.S.

The author spoke to LGBTQ Nation about Secret City, the fight for equality, and his optimism that marriage equality is here to stay.

Secret City opens with an overview of gays in political power from George Washington onwards but then starts to get more specific with Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Bill Clinton. Why did you choose these two presidencies?

I decided that World War II should be the beginning because that is when homosexuality transforms from being merely a sin and a mental disorder into being a national security threat. It’s considered the most shameful and unspeakable secret. There are all these euphemisms that I come across that people use to describe homosexuality because the concept is just “too loathsome to mention” as one senator said in 1942. There’s a fear that gays can be blackmailed so it’s about the rise of the national security state and the securitization of homosexuality.

That goes throughout the entire Cold War and ends in 1995 when Bill Clinton lifts the ban on gay people receiving security clearances. Those are the bookends for this era of what I call the “specter of homosexuality.” And that doesn’t mean that there isn’t, you know, gay history being made after Clinton. Obviously, there’s a lot, but just in terms of the official prohibition on gay people working in Washington, and this being a real liability and a danger. That’s the period of time that I think matters.

You write that many gay and lesbian individuals had a dual life and that being secretive would be beneficial since they are capable of compartmentalizing. What was the government’s reasoning behind this national security threat?

The fear was that gay people would be more susceptible to blackmail because of this dastardly secret that they had to keep. But there was actually never any evidence of that happening in the United States, that a gay person had turned over confidential information because they were gay.

In fact, there was a Defense Department study in the early ’90s when over 100 American espionage stories were analyzed. Of the six who were gay, not one did it for blackmail. It was for money.

What was one of the biggest discoveries that shocked you while researching the book?

The gayness of the Reagans, I didn’t really understand the degree to which they were surrounded by gay people. Reagan himself and his advisers were concerned that he might be perceived as gay because of his Hollywood background.

I came across an anecdote in his memoir when he ran for Governor of California. In one of his earliest films with Bette Davis, the director is basically asking him to play the role of the gay best friend and how uncomfortable this makes him. There was also a scandal when he was governor with Drew Pearson, the newspaper columnist, alleging that there was a gay network working for him in his office.

The big scoop in the book happened in 1980 just a couple of weeks before he was nominated, a group of Republicans tried to torpedo his nomination with allegations that he was being controlled by a right-wing homosexual network which The Washington Post investigated.

And so that kind of shed new light for me on his position on AIDS, I think there’s a surreal sensitivity or almost paranoia on their part that they would be seen as they’re sort of overcompensating for all of this. And you add to that the Christian right, the Christian evangelicals, who are a big part of a support base, and it’s sort of like an unholy alliance, you know. I don’t think the Reagans were personally homophobic in a way that distinguished them from other people in their generation — quite the opposite, probably. We know they had all these gay friends. It was really sort of tragic. A tragic combination.

But the President has the largest platform in the world. You don’t think that staying silent on the AIDS epidemic was homophobic?

I should maybe phrase it differently. Their views on this issue did not extend to not having gay friends because they had many gay friends. Were their public policies or lack thereof harmful to gay people? Absolutely. I’m not absolving them in any way but I think it’s important to learn this distinction.

It’s similar to Richard Nixon, who had horrible views about Jewish people and Black people. He expressed that on his tapes we heard and yet he was a strong ally of Israel and he implemented affirmative action. He increased affirmative action policies more than his predecessor. So politicians can have these vulgar views about people. Nixon had Jewish advisors in the White House, but he said all these terrible things about Jewish people. He also had a gay speechwriter, Ray Price, but spewed awful things about gay people. So it’s important to understand that the Reagans could be not personally homophobic in their personal relationships, but clearly, the President not uttering the word AIDS for over four years is unforgivable.

Nancy Reagan and Jackie Kennedy had a lot of gay men around them. How did they reconcile these relationships with their husbands and the political structure?

It’s a good question. Nancy was quite inscrutable about this. I think she was extremely protective of her husband because she wanted him to win. There was the feeling that “morning in America” was not compatible with people dying of AIDS, and wasting away in hospitals — that was not the image that they wanted to project. So I think that was how they were able to justify the lack of action on AIDS. And then just a sense that, you know, we have our friends, and they’re rich and tend to be powerful, right? And they’re different from the rest, right? They’re reserved, discreet, perhaps, they’re not ruffling feathers, you know, they’re fashion designers, society figures — not these sorts of scruffy activists in the street. They’re conservative like us politically.

Were there any recurring themes that you found through these administrations?

Most of these presidents had close friends or aides who were gay, yet they maintained policies that were destructive to gay people: FDR and Sumner Welles, Eisenhower and Arthur H. Vandenberg Jr., Lem Billings was JFK’s close friend, LBJ had Walter Jenkins and this other aide, Bob Waldron, whose story I report for the first time.

Almost without exception, we find that the presidents had these relationships, but they were able to compartmentalize and separate them from public policy. I think it changes with Bill Clinton, who gets a bad rap, rightly, for some things like the Defense of Marriage Act and “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” but he was the first presidential candidate to openly appeal to gay people as a candidate. It was a big deal in 1992, and I don’t think that’s appreciated. He also welcomed openly gay people into his administration and was the first president to do that.

Was Clinton’s presidency the turning point where being openly gay in Washington was no longer a taboo?

It depends on what level of power we’re talking about. The Civil Service Commission lifted the ban on gay people working in the civil service in 1975. Regarding high-ranking executive jobs in the White House, Clinton was a major turning point. He also lifted the ban on security clearances. There’s a whole stratum of jobs that gay people were officially barred from because you needed security clearance to have a real powerful job in Washington.

But it’s not like the closet ends at that point. I think on the left within the Democratic Party, it collapses around then, but within the early 2000s when George W. Bush was president and the federal marriage ban was debated in 2004 — that was a real season of outings.

By the time Trump became president, I don’t think homosexuality was really an issue within the administration. Trans rights certainly were, but I never came across stories of people being discriminated against because they were gay. In fact, Trump appointed the first openly gay member of the cabinet, Richard Grenell [Acting Director of National Intelligence], so I think it’s kind of neutralized now in Washington politics. I don’t think that being gay, except in certain congressional offices on the far right, is an issue anymore.

But do you think that we’re going back in time now with so much anti-trans and “Don’t Say Gay” legislation? Where are we right now in this cultural moment?

The story of gay people in America is a story of progress and then reaction to it. It’s two steps forward, sometimes three steps back or two steps forward, one step back.

Last year, a poll came out from Gallup that showed the percentage of LGBTQ people doubling over the past decade. That was sort of shocking to some people, and so now I think now we’re seeing the backlash to that. But I think it’s a temporary setback. I look at the polls, and I see that 55 percent of Republicans support gay marriage. That’s the first time there’s ever been a majority of Republicans supporting gay marriage. When you look at that and look at the younger generation, they’re much more open-minded and progressive. So, I’m not worried in the long term.

Even in light of having Roe v. Wade overturned, you have no concern that the Supreme court will strip away more LGBTQ rights including same-sex marriage?

I actually am not that concerned for several reasons. One is that the ruling majority opinion was explicit in saying that the legal justifications for overturning Roe should have no bearing on other cases and explicitly mentioned Obergefell. Yes, it’s true that Clarence Thomas in concurring opinion is calling for these cases to be reopened, but I don’t think there’s anything approaching the majority on the court to do that. But I also think that the abortion issue is very different from gay marriage. There, we’re talking about the fundamental debate revolving around a potential human life and when does life begin? It’s just a different argument about whether two consenting gay adults can have marriage rights.

There’s also no political movement like there has been for Roe v. Wade where there’s been a 50-year campaign and a very concerted political and judicial effort to overturn it. The conservative movement has been very explicit about that for five decades. I don’t see any sort of appreciable political movement in the United States to reverse gay marriage.

You specify that the story of gay people in America is one of progress and then reaction to it. Do you differentiate between gay and lesbian rights versus rights for trans, queer, and nonbinary individuals, or all they all under the same umbrella?

I believe all Americans are deserving of equal rights before the law and should not be discriminated against for any reason having to do with sexual orientation or gender identity.

There’s not a lot written about trans people, lesbians, and minorities in the book. Was that due to a lack of information or that they just didn’t have visibility?

The book is about political power in Washington during the Cold War era. I’m not aware of any transgender people who were working in congress, in the defense department — any of the institutions I was writing about. If there are other historians who want to dig them up and write about them, I encourage them to do so. I did not come across any, which isn’t to say that they might not have existed but I spent a lot of years scouring, and I was just also focusing on homosexuality. I think gender identity is a different issue. It’s not something that I feel particularly knowledgeable enough to write about.

“If you look at who had political power in Washington during this period of time, it’s almost exclusively white men.” — James Kirchick

And the same goes, unfortunately, for African Americans and lesbians. If you look at who had political power in Washington during this period of time, it’s almost exclusively white men. That’s the sad fact. I think our country would have been a much better place if it wasn’t just white men who had power during this period. But that’s who it was. This isn’t a history of activism, right? I do write about activists. I write about Frank Kameny and the Mattachine Society and the Gay Liberation Front. But it’s really a book about political power. It’s not as much about the people who are excluded from political power.

There are some lesbians in the book. But, you know, women were not in positions of power. It doesn’t really happen until the Clinton administration and you see high-ranking women get federal government jobs. By and large, women were not holding jobs that required security clearances. So lesbians were not susceptible to the same level of scrutiny that men were. Having security clearance made you more vulnerable in a way because you were under a higher level of scrutiny.

Also, gay male sexuality was much more heavily policed than lesbian sexuality. Gay men were looking for sex in public parks and public restrooms. They were coming into conflict with the cops a lot. They were victimized by entrapment rings and blackmail operations and were being killed by hustlers in cruising areas. Being a sexually active gay man was dangerous.

Can you talk a bit about the importance of the gay bars and discotheques for Washington government workers and their problematic nature for Black men?

This is an issue where race became quite prominent in the book — and racism within the gay community. These super bars started becoming popular in the early 70s. And they had racist carding policies; they’d ask for multiple forms of ID for Black men or they would impose certain dress codes. The Gay Liberation Front and other local gay groups protested these exclusionary policies. That leads to a separate Black, gay social life where they developed their own social clubs, private clubs, and also nightclubs, like the Clubhouse, which actually sounds like the most fun of all the clubs that I wrote about in the book. They had giant vats of acid-spiked punch and the best house music.

The Lost and Found was the closest thing that Washington had to Studio 54. Barney Frank described gay bars and clubs in Washington, at the time, as being like a neutral Switzerland in that you’d have Republican staffers, Democratic staffers, lobbyists for corporations, and people who worked at labor unions. These people who were antagonistic outside in their everyday life in Washington because they all shared this secret. There was a term called “the code” among gay people to protect one another. And that doesn’t really start to change until the 80s when AIDS hits and homosexuality becomes a political issue in a way that it hadn’t been. It becomes more of a partisan left-right issue. You see mostly conservative gay men being targeted for outing, or as it was called at the time “outage.”

Do you think that we have any modern-day equivalents of Roy Cohn who are holding offices of power and fighting against rights for the LGBTQ community?

Not that I’m aware of. I’m sure they exist. There’s a recurring theme of gay people behaving badly to other gay people. The closet makes people do terrible things but I’m not looking at Capitol Hill and finding a kind of person in the mold of J. Edgar Hoover or Roy Cohn. I don’t think the issue of homosexuality still incites the same passion and opposition. Mostly the transgender issue and gender identity issues are the new “outrage du jour” for some people. But when it comes to gay rights it’s hard for me to point to anyone.

“The story of gay people in America is a story of progress and then reaction to it.” — James Kirchick

Obviously, we have other lawmakers against us. There is a good-sized portion of the Republican House caucus that probably opposes gay marriage and if they had the ability to vote on it would probably reverse it.

How was it that both Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s Chief Counsel, and Black, gay civil rights leader Bayard Rustin were able to evade the scrutiny that other gay people were facing at that time?

Cohn was just incredibly good at what he did. He was bright, effective, and ruthless and McCarthy valued that. But it was also his undoing. The Army-McCarthy hearings brought down Joe McCarthy, and it was because of this relationship between Cohn and David Schine. I don’t think there was ever a sexual component to it but think it’s pretty clear that Roy Cohn was obsessed with Schine, but Schine wasn’t gay. Cohn was lusting after him. It was this homosexual lust and obsessive desire that basically brought down McCarthy. I don’t think it’s been fully appreciated that that’s what did it. Homosexuality was also not something that was openly discussed. So, perhaps, in a way, paradoxically, McCarthy thought that he’d be able to get away with this because no one would actually explicitly say what they thought was going on since the topic was so taboo.

Rustin was already out for his time. The civil rights leaders knew that he’d been arrested for homosexual offenses in the past. But like Cohn, he was so good at what he did. There was no better organizer. They knew that Strom Thurmond was their greatest enemy who was playing a very cynical game. They decided to stand by Rustin, and it was the first time in American history that a public figure survived the accusation of being gay.

Was there material that hit the cutting room floor or that found interesting that you wish you could have included?

It’s a big book. I tried to cram in as much as I could. I think it’s pretty thorough.