- Monkeypox was recently renamed mpox to get rid of the stigma that associated the disease with monkeys.

- The US is reporting an average of six mpox cases a week, down from over 600 in August.

- Mpox may never leave the country entirely, experts say, but current caseloads suggest vaccines and treatments are effective.

The Biden administration Friday declared an end to the public health emergency for the disease formerly known as monkeypox, which now accounts for fewer than 10 new cases a day in the United States.

The Department of Health and Human Services announced that it does not expect to need to renew the emergency declaration when it ends on Jan. 31, 2023.

“But we won’t take our foot off the gas — we will continue to monitor the case trends closely and encourage all at-risk individuals to get a free vaccine,” Secretary Xavier Becerra said in a prepared statement.

So how did an infectious disease that seemed to be raging out of control this summer become almost irrelevant three months later? It’s a combination of luck, good behavior and effective vaccines, experts say.

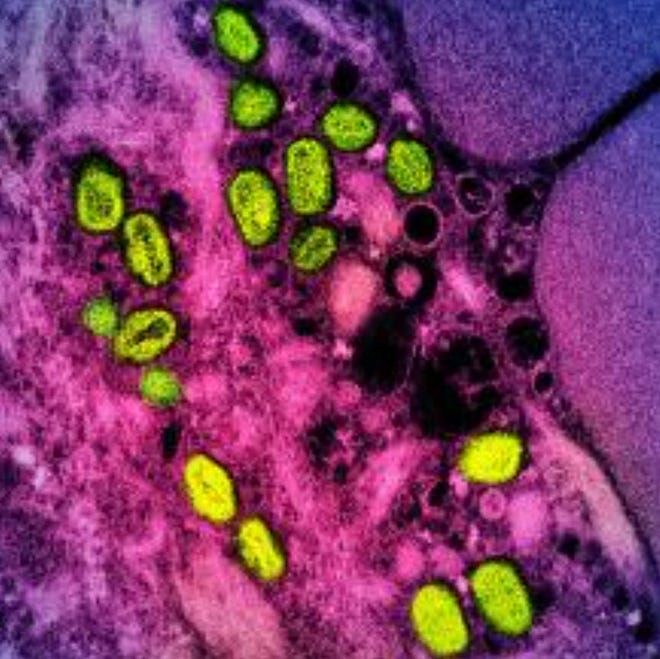

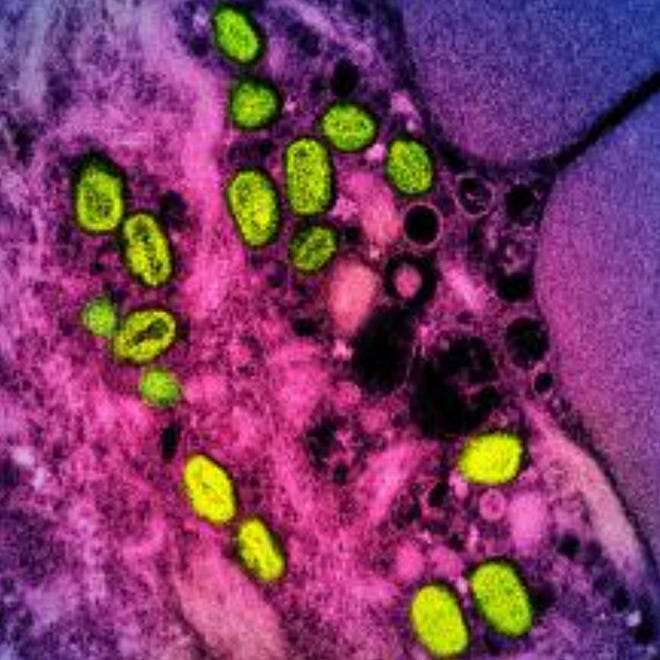

The World Health Organization last week renamed monkeypox to mpox to get rid of the stigma that associated the disease with monkeys. Monkeys don’t spread the virus, but it was first identified in them decades ago, hence the original name.

The virus — similar to smallpox but much milder — had been contained to the African continent until last spring, when it suddenly appeared in Europe and then the United States, spreading largely among men who had sex with men.

The first cases were detected in the United States in mid-May, with the peak reached on Aug. 1, when there were 638 cases reported. Now, the seven-day rolling average of cases is just six.

“The outbreak has been contained, but it’s not ‘mission accomplished’ because the virus is still here,” said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

More coverage on mpox from USA TODAY:

Mpox cases are down but not gone

Mpox may never leave the country entirely, said Dr. Daniel Griffin, chief of the division of infectious disease and travel medicine for Optum Health.

The high volume of cases — around 30,000 total, which was likely an undercount — “suggests that mpox is already widely distributed throughout the U.S.,” he said via email.

He and Schaffner both worry that more cases will be missed as the virus strikes populations that have not seen it before and physicians aren’t thinking of the disease.

Plus, people with the virus remain infectious for as long as three weeks, likely too long for someone to remain totally isolated. With widespread transmission there is also the potential that it will infect animal carriers — typically rodents — and then jump back into people.

But the fact that caseloads have been brought so low suggests that current vaccines and treatments are effective, Griffin said.

The mpox virus typically requires significant contact to spread. Unlike COVID-19, which can pass easily through the air, physical contact with open sores or bodily fluids is the most likely route of transmission.

The outbreak was mainly among men who have sex with men, not because mpox is a “gay disease” or an African disease, Griffin said, but because “mpox is an infectious disease.” Griffin said the old name for the virus had “racial and stigmatizing associations and would have liked this to have been acknowledged and asked on much sooner.”

Advocates also supported the name change.

“Public health officials and authorities must remove every barrier to improving understanding about how viruses spread and who is most affected,” said Sarah Kate Ellis, president and CEO of GLAAD, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer media advocacy organization, in a statement.

“Decades of public health research shows stigma slows down testing, treatment, access to care, and vaccine equity, particularly in communities of color, which are often disproportionately impacted by global outbreaks.”

Gay community stepped up to stop spread of mpox

Griffin credits behavior changes within the gay community for stopping the virus’ spread.

“We were fortunate with the mpox spread that the most impacted population does not suffer from widespread embracing of the anti-science misinformation and were quick to embrace vaccines, proactive about getting treated, really did reduce risky behaviors,” he said via email.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s initial messaging around mpox frightened many people who were not at any risk for the disease and did not encourage action among those at high risk, said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist and professor at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

Once the messaging became more specific, the gay community took action and brought infection rates down, he said.

“People were so terrified of the scars and visual look of it that everybody rushed out to get (vaccinated),” he said.

Some people are declaring on dating apps whether they’ve been vaccinated or recovered from mpox, Chin-Hong said. If another outbreak were to occur, he said, “there’d probably be hopefully a faster calling in the troops and putting in all the interventions.”

Changing mpox vaccine policy

When the outbreak was at its peak, the CDC decided to conserve vaccines by delivering a smaller dose into the skin rather than underneath it.

The intradermal shot seems to have been effective in the short term, Schaffner said, but now he’d like to see a return to intradermal shots, which are probably more effective and less likely to leave a mark on the skin.

The intradermal shot often leaves a colored circular spot on the forearm, “almost like a scarlet letter,” Chin-Hong said. Having that scar or scars from an mpox infection, he said, “you’re kind of declaring yourself as part of the community, which not everybody is necessarily comfortable with.”

An intradermal shot doesn’t leave a permanent scar.

The real benefit of an intradermal vaccine is the ability to get more doses from the same vial, Chin-Hong said, which means more could be provided to the rest of the world.

OVER THE SUMMER:Biden officials announce 1.8M mpox vaccine doses

The outbreak peaked at a time when there were a lot of social events. Now, with Pride season over, the virus has died down but could flare up again when social activities resume, Chin-Hong said.

Most of the outbreak was driven by cases in major cities, particularly New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Chin-Hong worries that there may be undetected cases in rural and other areas where doctors are less likely to recognize the symptoms.

The open sores were both painful and visible, making them socially stigmatizing, he said. “It was a visible reminder of what community you belong to.”

It also brought up memories of Kaposi sarcoma, purplish skin tumors that had been one of the most obvious symptoms of the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, before medication turned it from a universally lethal infection to a chronic one.

“To me, what was striking about mpox was the fact that it caused so much suffering,” he said.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

More health new from USA TODAY