The team behind a Nashville documentary screening Oct. 5 at the Nashville Film Festival is hoping the stories of human struggle, vulnerability and triumph it brings forward will help turn the invisible visible.

Directed by Nashville resident T.J. Parsell, “Invisible” is a film that intends to shine a light on the numerous gay female songwriters who have, over the years, helped feed country music industry leaders’ chart-climbing endeavors from the background or in silence.

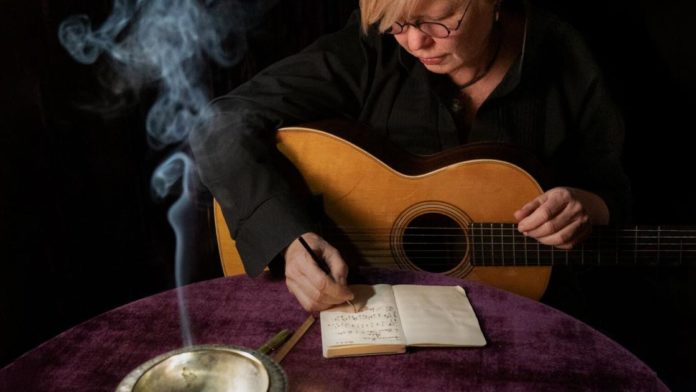

Singer-songwriter Pam Rose is one of 12 songwriters interviewed, women who collectively have written successful songs for artists such as Tim McGraw, Willie Nelson, the Judds, Reba McEntire, Martina McBride and Vince Gill, to name just a few.

Rose, herself a Grammy nominee and BMI “Million-Air” Award winner, helped outline the examined issue.

“Sure, of course, there are a lot of people in the country music audience that don’t like people being gay, of course that’s true, but the corporate mentality blows that way out of proportion,” Rose said. “For the most part, nobody cares. There’s a small percentage of people in the audience that care, but we were never able to get to them as artists.”

For Parsell, the filmmaking process was as much about learning about and appreciating the individual stories of the women as it was understanding the conservative-minded gatekeeping dynamic of the industry over the decades.

“These women had a lot to say, and their journeys were riveting and moving, especially given their backgrounds in the South, many of them growing up in religious homes,” Parsell said.

“It was listening to and learning about their own journeys in terms of accepting their sexuality and how that informed their art and how they dealt with an industry that is not all that welcoming to people that are different,” he continued. “How did they do that? What choices and compromises did they make to find a place for themselves in this industry?”

Parsell said he found himself inspired by their stories.

“I think the thing that inspired me a great deal was, despite all of the forces that seemed to conspire to keep them down, they persevered anyhow. Their voices came through anyhow,” Parsell said. “Their art and even their triumph deeply informed their work, and if you look at the collective catalog of these women, we’ve all been touched by them. … I thought this is a story that has to be told.”

From the beginning, the subject matter hit home on a personal level for Parsell, a gay man who kept his sexuality hidden from those with proximity to his software sales career in the 1980s and ‘90s.

“Part of my job was to build relationships, and talking about my boyfriend was not going to do that,” Parsell said. “Having lived through that experience and knowing what being in the closet cost me … all of those things sort of informed the approach I wanted to take with these women.”

Several of the songwriters interviewed deemed the film as good a moment as any to share publicly their long-held secrets for the first time, despite being longtime contributors to the country machine.

“It was so emotional,” said Rose, noting that much of the group knew each other well and in many ways experienced the moment as a collective. “The plethora of emotions I felt was unlike very much else I’ve ever felt.

“It was intriguing to do, and it seemed like the right time. “And it was an opportunity to address the very small boxes that Nashville and country music have around things. … It’s the limitations. It’s the fear factor.”

Over the several years spent making the film, Parsell found hardship in each story, some from the day each person arrived in Nashville hoping for careers as visible artists.

“It’s been very difficult being in Nashville and feeling that sense of oppression and repression,” Rose said. “If you have good instincts and good intention, you just know what’s going to tank your career or what isn’t.

“All of us songwriter people, that have the hit records, that have over 30 million air plays, we all came here to be artists, all of us, and quickly realized that wasn’t going to happen if we were really going to be ourselves and be honest,” she said. “Songwriting was a thing to fall into. You didn’t have to dress up, and the checks came in the mailbox.”

One example of fear turning into reality during the film comes from Chely Wright of “Single White Female” and “Shut Up and Drive” fame, whose songs had experienced success until she very publicly came out in the 2010s.

“When she came out, that was it. Just crickets,” Parsell said. “One disc jockey even said to her, on the air, ‘Girl, what were you thinking? There’s some things we don’t need to know. We just want you to shut up and sing.’ Now that was a real blatant example.”

The moment, along with the near suicidal experience preceding Wright’s decision to come out, illustrated one tangible example of what Parsell characterizes as usually being a quiet problem.

“The thing about Chely’s story, it wasn’t like a big slamming door,” Parsell said. “It was just a very quiet nudging away.”

Parsell said learning about the dynamic of country radio expanded his outlook on the totality of the problems within the industry, particularly when examining the idea that women get just 13% of country airplay, according to The Washington Post.

“I started to scratch my head not long into the project and started to wonder how much of what these women are feeling is because they’re gay and how much is because they’re women?” Parsell said.

Country radio, he found, was mired in negative sentiment among those he interviewed.

“Unless you have radio airplay, you don’t have a career. Radio is controlled by just a few corporations and a lot of men who abuse that power,” Parsell said. “There’s a lot of sexual harassment that goes on in the radio circuit that everybody knows about, but few people are willing to talk about it because they’re afraid.

“Many of the folks I talked to didn’t know a single woman (artist) who hasn’t put up with this nonsense on the radio circuit.”

He offered his reasoning as to why aspects of the country music industry exist in their current form, not keeping pace with society’s cultural evolution.

“I think the industry is still run by too many men,” Parsell said. “Women are way underrepresented.”

For her part, while acknowledging that the industry is, to a limited extent, at the very least moving slowly in the right direction, Rose offered up her hopes for the film.

“I would like to see the conversation. In a perfect world, we would sit down and share this with record executives. I don’t think that’s going to happen, and I don’t know that that would change anything, but usually what happens, in my estimation, is the ground-up philosophy helps,” Rose said. “When something’s honest and emotionally truthful, that just inevitably does good.”

Echoing that sentiment, Parsell placed his emphasis on the strength of the women themselves.

“When somebody’s really vulnerable and open, it touches something inside of us and it creates empathy because, at the core, we’re all the same,” Parsell said. “The thing that I would love people to take away from this film is to be as inspired as I have been by having the privilege of spending the time with these women.

“In spite of a number of factors that conspire to keep them down — whether it be their family, religion, the industry, radio, fear, internal fear of stepping in and being out — in spite of all these things, these women’s art came through anyhow and their voices came through anyhow, and they made an indelible impact on all of us.”