I. Executive Summary

The twenty-first-century race for technological supremacy is contested across multiple domains and moving at breakneck speed. Today’s innovators will own tomorrow’s future. As it stands, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU), and like-minded nations risk falling permanently behind. To win this race, the West must develop a common approach to integrating emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs). The Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) led a year-long study to produce a transatlantic strategic framework for competing in defense and dual-use technologies. The project aims to raise awareness, spark discussion, and provide a shared framework for cooperation on these issues among NATO, EU, and national government officials, as well as industry leaders. Ultimately, it seeks to spur the development of a transatlantic defense technology strategy for the US and Europe, which will be critical for the West in light of rapid advances by Russia and China.

The study makes three important contributions to the ongoing debate. First, it offers a clear, replicable methodology to identify and prioritize critical technologies as they emerge. Second, it sets forth nine core pillars to form the basis of a common transatlantic policy framework for defense tech issues. Third, it outlines short-term recommendations to implement the policy framework. Together, these elements comprise a compelling strategy for enhancing transatlantic cooperation in defense technologies.

Key Findings: Policy Pillars and Recommendations

Pillar 1: Forge a Common Assessment of the Threat Competition

- EU member states and allies must utilize the EU Strategic Compass and NATO Strategic Concept as starting points to develop a shared understanding and assessment of the tech competition and create a sense of urgency for policymakers to act.

- The US and EU should use their dialogue on security and defense to align approaches to Russia and China.

- NATO should leverage its Political Guidance and Defense Planning Process to encourage a forward-looking approach to defense tech investment.

- NATO must adapt its doctrine, training, and warfighting techniques to create a common intelligence and operational picture of the strategic environment.

Pillar 2: Facilitate Faster Adoption of Technology

- To focus their efforts, allies should agree to work on three to five key use cases for each of NATO’s nine priority technologies and develop, procure, and deploy each tool accordingly.

- NATO, the EU, and their member nations should focus funding on supporting procurement and adoption, as opposed to strictly research and development (R&D). These funds should have clear transition partners to provide a clear path for companies to engage and thrive in the NATO ecosystem.

French soldiers scan the horizon for possible threats with the French weapon system during exercise Ramstein Legacy 22. Credit: NATO

Pillar 3: Improve the Regulatory Environment

- The US ought to strengthen its defense industrial base by opening it to more close, trusted allies.

- The US and EU could catalyze a new dialogue on export controls and create a transatlantic tech access clearing center to reduce barriers to multinational tech cooperation.

- To widen the pool of new capabilities, the US should streamline the process for establishing proxy boards, required for foreign tech companies to operate in the US.

- The US should create a corps of top tech talent (US citizens) who may maintain security clearances even if they leave government or classified contracts. This would improve the mobility of ideas and talent, ensuring they are able to support classified work across the innovation ecosystem with limited notice.

- Euro-Atlantic nations should make it more difficult for Russia and China to access Western commercial technologies through deeper coordination to tighten export controls, foreign investment screening, foreign research partnerships, etc.

- Europe and the US must work together to offset major defense tech supply chain vulnerabilities created by economic dependence, particularly in manufacturing and semiconductors, on China.

- NATO and the EU should create a list of shared principles for governance of dual-use and defense technologies.

Pillar 4: Incorporate Nontraditional Partners to Inspire Radical Innovation

- Rather than prescribing a solution and over-specifying requirements, governments should present a challenge to industry and academia with competitions and let them develop a wide range of possible solutions. Governments should also allocate funding to these competitions in a manner similar to the XPRIZE Foundation’s approach.

- To encourage scaling and production opportunities, governments could establish an incentive program in which, if a new capability succeeds beyond the first procurement to a second customer, the first is paid back or rewarded monetarily for taking the initial risk.

- Euro-Atlantic governments should convince more venture capital (VC) firms to invest in defense startups, engaging them early in the conceptualization process of innovation initiatives. Such engagement can include facilitating VC contributions to early rewards from government and government providing funds to match those which VCs provide to startups.

- Governments should utilize more agile contract models that have quicker award timelines, more money up front, and more flexible milestones for evaluating progress and measuring deliverables, especially to accommodate start-ups.

- Governments should find ways to lease intellectual property associated with new tech, as opposed to needing to buy it outright.

- Governments should create a specific category of awards for nontraditional companies which are capped at a certain value to minimize risk for program managers.

- Large companies should offer more programs for nontraditional players, with whom they often partner or subcontract, in which they offer to hold their security clearances, provide workspaces, and give tutoring for navigating government contracting without onerous terms for the startups.

- The EU should provide a platform for small, innovative companies to demonstrate their technologies to multiple countries at the same time to maximize resources.

- The US and larger European countries should explore lessons learned from small countries such as Latvia and Estonia which have never had traditional defense primes.

- Nontraditional players who have been through government contracting processes should collaborate on a book of best practices to help future start-ups.

Pillar 5: Continuously Scout for Technology Solutions and Talent

Governments should educate civil servants and military officers on tech issues earlier in their careers and provide realistic pathways to use these skills as they move up the value chain. Governments should provide more opportunities for civil servants and military officers to undertake short-term assignments in tech companies and vice versa.

- NATO and the EU should create an accessible set of shared definitions of key technologies.

- NATO, the EU, and their nations should host more “pitch days” and innovation contests with rapid, commercially significant awards attached to discover potential new solutions and talent.

- NATO and the EU could create a shared database of relevant startups discovered through these scouting events ensuring individuals across the organizations involved can benefit from this knowledge.

- NATO, the EU, and member nations must employ more people dedicated to extracting large amounts of information websites, also known as “scraping” technology that comes from the field, scanning the horizon for new opportunities, and sharing that information among allies. These individuals could be aggregated into a network of tech experts across transatlantic countries.

- More “tour of duty” assignments should be made available and accessible to leading tech and business talent to bring their expertise to government over the course of one to three-year job posts. Governments must work together, through screenings of research partnerships and university collaborations, to prevent foreign malign influence more effectively by capitalizing on talent in the tech sector.

Pillar 6: Increase Testing and Evaluation

- Governments should provide more sustained, long-term, fungible resources to support prototyping, testing, procurement, and private sector engagement initiatives that facilitate industry-warfighter contact.

- NATO and the EU should develop shared parametersacross allies to evaluate tech performance, success, and risk.

- NATO should give nations more opportunities to test advanced technologies (beyond TRL-5/6, where nations have already done initial testing) in large-scale field exercises.

- Governments and institutions should undertake more tabletop exercises and wargames with emerging tech components. This should involve leveraging synthetic environments and giving nations more opportunities to test advanced technologies in large field exercises.

- Governments should provide more implementation pathways from testing and evaluation. Contracts should allow for immediate selection or down-selection for future development of technologies that prove successful.

- NATO should develop a more robust internal architecture for digitizing the Alliance. This would allow for more rapid testing, evaluation, and eventually networking and integration of emerging capabilities across all domains.

Pillar 7: Enhance Data-Sharing Among Allies

- The transatlantic community must develop more resilient systems for data collection, sharing, and storage, as well as common standards for data formats, classifications, and transfers.

- NATO nations must build more trust around risk mitigation surrounding data-sharing. The default approach must involve nations sharing as much data as possible, with justifications required for not sharing.

- NATO and its allies should invest in new technologies that support intelligence activities and streamline or secure information gathering, storage, and sharing processes.

- Governments should provide start-ups with the means to test their capabilities using government data, prior to finalizing a contract, to increase attractiveness and feasibility.

Pillar 8: Improve Interoperability and Standardization

- NATO should invest in and empower monitoring committees for enforcement and implementation of existing interoperability standards among allies, while encouraging the EU to adopt these standards as well.

- NATO and the EU should consider developing more material standards at different places along supply chains, especially for emerging defense and dual-use technologies.

- Allies should more effectively leverage national training centers to practice interoperability with new technologies at the corps and tactical levels.

- Euro-Atlantic nations must take stock of lessons learned from Russia’s war in Ukraine regarding the need for rapid production and delivery of interoperable systems.

- Develop a NATO capability to integrate diverse non-NATO military units and equipment into coalition efforts.

Pillar 9: Connect and Better Align Existing Tech Efforts

- NATO’s Defense Innovation Accelerator (DIANA) should embody a flexible approach aimed at creating multiple innovation ecosystems across countries for different fields of technologies.

- NATO could task its military authorities (international military staff), who are responsible for military budgets, to serve as coordinators for all efforts across the Alliance related to prioritizing technological capabilities and concepts for further development and operational experimentation.

- To bring together the EU, NATO, their member states, and industry players, the transatlantic community’s innovation efforts could be based on a “stone soup” model, in which each stakeholder offers what they are best suited to do. Nations could also explore a more explicit division of labor to create key technological capabilities.

- Leading allies and partners could also explore a G7-style framework where different nations, institutions, and entities (including critical industries) come together via a special envoy to establish innovation benchmarks and tech initiatives among willing nations.

- Governments should make more dedicated efforts to establish cross-governmental coordination on technology.

- The NATO ACT Innovation Hub could create a more open forum that involves other NATO entities in the development stages of their activities.

II. Introduction

Since the end of the Cold War, the US and its NATO allies have enjoyed a capability advantage over state and non-state adversaries. This advantage gap, however, has drastically shrunk in recent years. While the US and its allies spent the last two decades prioritizing counterterrorism capabilities over innovative near-peer technologies, Russia and China have been utilizing EDTs to close their traditional capability gap with NATO. These technologies – such as autonomous systems – do not seek to simply mirror NATO capabilities, but instead mitigate or even leapfrog them. As a result, NATO is no longer the main driver of new defense technologies and has fallen behind its competitors in key emerging technology areas.

To maintain their strategic edge in an increasingly contested world, NATO and EU nations must collaborate to leverage EDTs to enhance shared security and better prepare for future crises. Particular attention must be paid to near-term, dual-use, transformative technologies, which are rapidly affecting and overturning traditional defense methods. The ability to develop and deploy these game-changing technologies more effectively than China and Russia will shape the global role of the transatlantic Alliance in the coming decades. Allies are waking up to the need to forge a common approach to defense technology, but the window to act is narrowing.

Two major challenges inhibit a common approach. First, NATO and EU member states are each focused on somewhat different technologies, while innovating and investing at radically different levels and speeds. Recent priority lists and policy efforts, such as NATO’s DIANA and the Hub for EU Defence Innovation (HEDI) within the European Defence Agency (EDA), have rightly sought to address this and hold important potential to help the Alliance pursue EDTs to transformative ends. Still, insufficient coordination over time among nations and institutions has produced duplicative efforts, inefficient spending, and a concerning interoperability gap, most acutely between the US and European allies. Second, Euro-Atlantic allies diverge on key policy issues surrounding the defense application and adoption of EDTs, such as implementing common technology governance structures and managing supply-chain issues. The result is slow and stilted decision-making that impedes the Alliance’s ability to ideate, develop, and deploy defense technologies quickly enough to compete with Russia and China. These dynamics undermine NATO’s collective defense, internal cohesion, and strategic edge over Russia and China.

To address these issues, CEPA has undertaken a year-long study to set forth three elements that are missing from current literature and policy debates: 1. A systematic ranking of key defense technologies to prioritize that will give the Alliance as a whole the most strategic “return on investment” and elevate its competitive edge; 2. A common framework for addressing policy issues around EDT development and integration; and 3. A list of concrete steps toward these ends for NATO and EU member governments to take in the near term. This project will have immediate policy relevance for Euro-Atlantic government officials, helping to spur discussion, unite thinking, and motivate the development of a transatlantic strategy for defense technology.

The project’s methodology primarily involved qualitative analysis through literature research, interviews, and consultations with dozens of officials and experts across national governments, NATO, the EU, industry, think tanks, and academia. This included field visits to Brussels, London, Paris, and Washington, DC to examine areas of divergence and convergence across Euro-Atlantic countries, institutions, and companies. To inform the study and gather critical feedback, the research team at CEPA also led two workshops and two red-teaming sessions with officials, scholars, and practitioners working on these issues. CEPA also presented the initial findings of this study at the 2022 Munich Security Conference.

To examine current gaps, identify solutions, and forge a sustainable path forward, this study proceeded in three phases. First, the research team assessed priority technologies through an organically assembled EDT Innovation Matrix, which ranks EDTs that the overall alliance should prioritize based on five key factors (time, need, cost, policy challenges, and impact). The assessment’s scope was confined to dual-use technologies, which are least understood and most contested within the Alliance, and yet extremely valuable and practical, given their diverse applications. Dual-use capabilities have the benefit of consistent potential revenue from defense organizations, coupled with the accelerating impact of commercial funding, which makes them most viable. More specifically, the assessment examined such technologies with near-term application timelines (i.e., currently deployed or will likely be deployed within five years), which are most relevant for immediate NATO and EU planning. This study also assessed the Alliance’s capabilities as a whole, with supplemental analysis of comparable Russian and Chinese capabilities to understand NATO’s threat environment.

Based on these parameters, the research team identified and assessed five technologies as top priorities for the Alliance’s strategic edge: space-enabled capabilities, unmanned systems, hypersonics, edge computing, and cognitive influence capabilities. These were selected due to NATO’s relative need based on the current and foreseeable threat environment as well as Russian and Chinese capabilities in those areas, feasibility for realization, and the transformative potential of these technologies to impact the Alliance’s capabilities as a whole vis-a-vis China and Russia in future warfare. As explained in this section of the paper, the research team decided not to focus on artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) due to the extensive research, analysis, and literature that already exists and the fact that the authors fundamentally view AI/ML as a key enabler for all the above EDTs, rather than as a standalone capability. For further discussion, there is an additional section on excluded technologies later in this paper.

Second, the research team developed a common strategic framework to address policy divergences by formulating nine key policy pillars to guide transatlantic defense tech cooperation. Third, the researchers set out next steps for policymakers. This component of the project includes 50 short-term, concrete recommendations under each policy pillar to help nations and institutions implement the strategic framework. Finally, the research team developed a conceptual roadmap that includes one-year, three-year, and five-year key performance indicators (KPIs) to provide quantitative indicators to measure progress in implementing these recommendations as they evolve. It should be noted that the roadmap and KPIs which feature in appendix 1 of this paper represent only a working concept that will require further development and refinement over time.

This project was designed to have immediate policy relevance for NATO and EU member government officials, helping to spur discussion, unite thinking, and motivate the development of a transatlantic strategy for defense technology. The assessment’s five-factor EDT matrix provides a consistent and replicable process that transatlantic policymakers can use to reassess priorities as new technologies emerge. The assessment will offer compelling data for why these technologies should be prioritized, providing a pragmatic basis to drive further Allied consensus around these priorities in the future. The findings of the assessment seek to inform future defense strategies, budget decisions, and investments in Allied capitals and Brussels. The study’s strategic principles for a common policy framework will provide a foundation and shared language for Allied leaders to bridge divergences between US and European tech policies. By outlining a list of short-term policy recommendations in support of the framework, the study also provides a clear roadmap for Allied government officials to harness defense technology to strengthen NATO’s collective defense and strategic edge for the years to come.

III. Context and State of Play

In recent years, EDTs have quickly become integral to discussions about strategic competition and future warfare. As these technologies have advanced and proliferated, transatlantic policymakers and defense planners have begun to recognize the importance of these capabilities to the West’s strategic edge over its adversaries and competitors. While the term “innovation” has become ubiquitous, making its way into nearly every speech, strategy, and policy document, Euro-Atlantic nations and institutions have much work to do to effectively harness EDTs for collective defense and deterrence. Undoubtedly, the transatlantic community has made significant, rapid progress over the last three to five years to this end. However, significant gaps in progress remain due to a confluence of factors. To adequately understand and address these challenges and chart the way ahead, recent progress and remaining issues are explored below.

From the Global War on Terror to Strategic Competition: The Evolution of NATO, Russian, and Chinese Defense Tech Capabilities

After the Cold War, the US, NATO, and the world at large shifted focus to combating terrorism and capacity building in fragile states. As a result, the urgency to develop and field new systems to combat potential near-peer competitors eroded. Without this motivation, NATO and its allies – especially larger ones – continued to develop and acquire complex, bespoke platforms which assumed permissive operating domains, such as billion-dollar satellites, multi-billion-dollar aircraft carriers, and GPS-dependent ground and air assets. This approach yielded incrementally better capabilities, but no truly game-changing technologies. Concurrently, several of NATO’s largest allies drastically cut funding to their militaries and defense sectors, severely degrading previously robust capabilities. While this approach was sufficient for fighting technologically inferior non-state actors in the global war on terror, it has left NATO vulnerable in today’s renewed era of great power competition with Russia and China.

In the meantime, Russia and China have taken advantage of NATO’s pause in defense innovation to develop differentiated and comparatively more cost-effective area denial capabilities designed to mitigate NATO’s traditional strengths. Over the last decade, China has risen as a scientific and technological powerhouse, while Russia has more creatively and assertively pursued asymmetric advantages. Both the Kremlin and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have invested in innovation programs and EDTs that are beginning to change the character of modern warfare to their benefit.

Leveraging their highly centralized systems of government, Russia and China have facilitated cooperation between defense and commercial establishments to develop technologies that have already proven advantageous across military and civilian contexts. Because these authoritarian states can mobilize all elements of national power toward their technological goals, they have moved much faster than NATO or the EU, which comprise several sovereign nations bound by slow-moving, transparent, democratic, and open-market processes. China, and to a lesser extent, Russia have made major strides in artificial intelligence, military robotics, and autonomous systems, for example, which lower the cost and operational risk for Russia and China in a potential fight against NATO, whose greatest advantages are high-end, complex capabilities with high opportunity costs for their usage (e.g., manned aircraft carriers). This has significant implications for NATO as a whole, creating operational challenges and rapidly narrowing its traditional capability gap. Beyond these technologies, there are several key areas where Russia and China individually have managed to gain parity or even exceed NATO capabilities or develop tools to mitigate NATO advantages. Most notably, this includes hypersonic and anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons or counter-space capabilities.

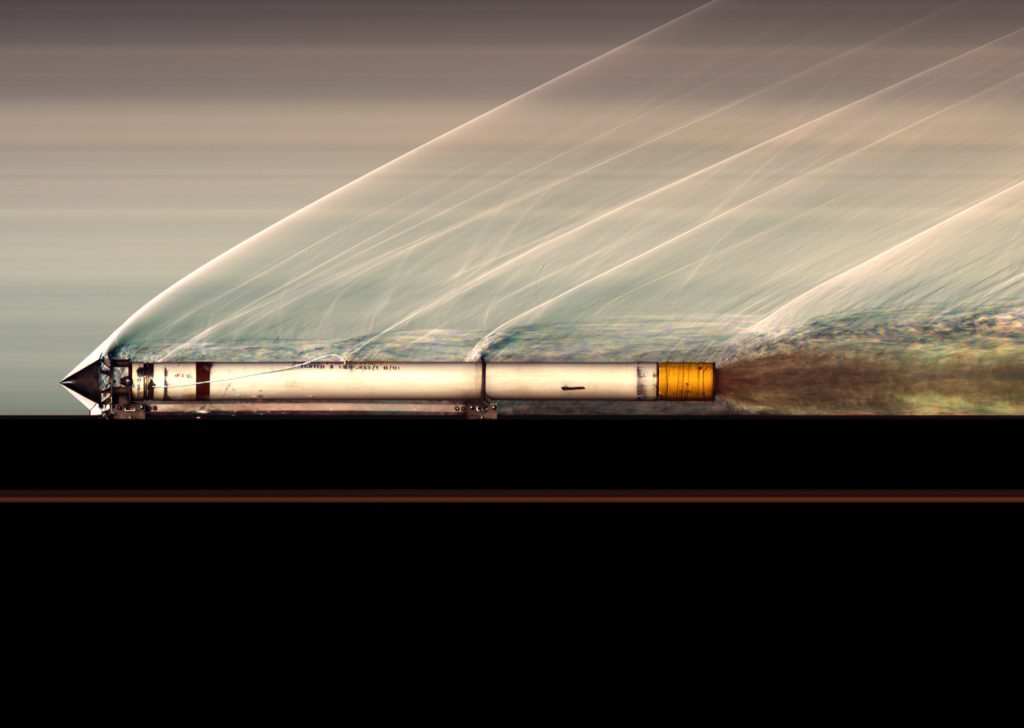

Russia and China have developed and deployed hypersonic cruise missiles (HCM) ahead of the US and other NATO nations. In Europe, Russia has created similar anti-access area denial (A2AD) bubbles over key areas near the Baltic and Black Seas that would restrict NATO’s navigation and operation in those critical regions. Its hypersonic weapons, such as the 3M22 Zircon, can fly so fast and low that they can penetrate NATO’s traditional anti-missile defense systems and leave insufficient time for Allied response. These weapons provide Russia with a means of contending with NATO’s size, mass, and key capabilities like aircraft carriers. However, some of the limits of Russia’s military and technological capabilities have been revealed by its failures during the war in Ukraine. China, in particular, has ramped up investment in hypersonics to develop enhanced A2AD bubbles which would prevent the ability of the US and its allies to project power in an expanding area. The proliferation of China’s HCM arsenal is intended to mitigate the US’s blue-water navy advantage. An array of carrier-killer weapons such as the DF-26 and CH-AS-X-13, at a cost of less than $100 million can disable or even, in the event of multiple strikes, sink a $13.3 billion US aircraft carriers with over five.

ASATs have similar, but even farther-reaching implications. NATO capabilities are highly reliant on space-enabled capabilities including GPS, satellite communications, and geospatial intelligence for situational awareness, conducting operations, and engaging in conflicts. Without these, the ability to understand the battlespace, coordinate, and react is completely disrupted. Knowing this, Russia and China have separately developed and successfully tested ASATs multiple times over the last fourteen years to counter NATO in space.

These weapons pose a threat to commercial, civil, and defense assets ranging from telecommunications to the International Space Station to bespoke intelligence satellites. In the latter case, a $60 million ASAT from Russia or China can readily destroy $2 billion in national security satellites, for example. Further, as ASATs are used, particularly if on low-earth orbit (LEO) based satellites, they significantly increase the chance of a cascading effect, which could destroy dozens or even hundreds of satellites, functionally turning LEO into a dead zone. This would be an economic catastrophe for the West (and the world at large). It would also render most, if not all, of NATO’s space capabilities inoperable, leaving the Alliance operationally deaf and blind.

Nevertheless, in some ways, tight government control has stifled radical innovation in Russia and China, compared to Western countries that encourage creative thinking, dissent, and risk-taking. In fact, to compensate for shortfalls in indigenous innovation, both Russia and China have orchestrated cyber espionage, hacks, and intellectual property theft from NATO countries in order to reverse engineer their own version of key EDT capabilities. At the same time, their authoritarian approach has allowed the Kremlin and the CCP to actively set spending priorities, manipulate talent programs, promote national champion companies, and accelerate the development and deployment of EDTs more effectively than the free market, open systems in the US and NATO countries.

Unlike NATO Allies, Russia and China have also avoided constraining their innovative efforts by establishing ethical standards, legal principles, and political consensus around tech governance. Development of technology based on shared democratic values is key to ensuring that the deployment of such technologies does not undermine the strategic standing of democracy on the international stage. However, the development of such technology requires a proactive and deliberate approach to ensuring that these values are upheld. How they are to be integrated into EDTs requires prioritizing them as early as possible in the tech development cycle to ensure final products inherently embody democratic values in a way that allows them to quickly and effectively be deployed.

Looking ahead, Russia’s defense innovation efforts will likely suffer gravely as a result of its unprovoked war in Ukraine, which is ongoing at the time of writing, as well as the increasing pressure from Western sanctions that are severely damaging Russia’s economy and defense industry. While the longer-term impacts of these dynamics on Russia’s overall military and technological capacity are not yet fully understood, this creates a larger window for NATO to elevate its own technological edge. Chinese state-driven innovation efforts, however, are set to expand, intensifying the growing techno-strategic competition between Beijing and the transatlantic alliance. To ensure China does not continue to disrupt this competition in its favor, the transatlantic alliance must work together to boost cooperation on defense tech issues.

Transatlantic Defense Tech Cooperation: Current Efforts and Gaps

Over the last few years, US and European officials have recognized the need to cooperate around EDTs to enhance collective defense and more effectively compete with Russia and China. NATO, for its part as the premier collective defense forum for Euro-Atlantic allies, has moved remarkably quickly to sharpen its focus on technology. It has emphasized EDT-related issues through its public messaging, collaboration with think tanks and civil society, and the 2030 reflection process. In the past three years, NATO has also devised an EDT strategy, released a major report tracking defense tech trends, boosted projects through the Innovation Hub at Allied Command Transformation (ACT), and released the first comprehensive AI strategy for the Alliance in October 2021. Perhaps most notable has been the creation of NATO’s Defense Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA), whose chartered goals are to “harness new academic, commercial, and entrepreneurial start-up technology; test and develop it as potential defense capability; and connect it more quickly to military end-user operational requirements.” DIANA is intended to operate alongside the NATO Innovation Fund, the world’s first multi-sovereign venture capital fund slated to invest 1 billion euros in early-stage startups and other investment funds developing dual-use technologies relevant to NATO.

The Madrid Summit in June 2022 built on this progress, as the Alliance focused on the Russian threat, enhancing capabilities, and, most critically, on EDTs to aid in doing so. This EDT focus was underscored in its new Strategic Concept, released at the Summit. The Strategic Concept states: “Emerging and disruptive technologies bring both opportunities and risks. They are altering the character of conflict, acquiring greater strategic importance, and becoming key arenas of global competition. Technological primacy increasingly influences success on the battlefield.” Russia’s actions in Ukraine have brought a new sense of urgency to the Alliance and highlighted the need to focus on EDTs to support the mission of deterrence and defense in Europe. The Concept places particular emphasis on space, not only as a critical technology area but more explicitly as a “warfighting” domain. Prior to 2019, NATO had avoided characterizing space in this regard in all policy documents. NATO’s new strategy clearly places emerging tech as a core element of its approach to the current and future security environment.

EU Efforts

While NATO has a critical role to play as the core transatlantic defense organization, it is important to recognize the EU’s litany of complementary resources and mandates related to funding, regulation, and legislation around EDTs. These have also had a massive impact on the innovation ecosystem in Europe. The EU operates entities such as the European Defense Agency (EDA), European Defense Fund (EDF), Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), and more that complement NATO’s mission. It has also developed its own technologies roadmap, aimed to create synergy between various European defense, civil, and space industries. Importantly, the EU recently launched the Hub for EU Defense Innovation (HEDI) within the EDA. The EU-US Tech and Trade Council, established in June 2021, also provides a transatlantic forum to coordinate on technology and related economic policies rooted in shared democratic values. Additionally, NATO-EU collaboration on projects such as the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats and the publishing of various joint declarations identifying emerging tech as a key area of collaboration for the two organizations prove the utility and necessity of working in tandem on these issues.

National Efforts

Aside from NATO and EU efforts, individual nations have also played a crucial role in advancing EDT and innovation initiatives. Various countries have prioritized technology as part of their own national security, having developed their own national EDT and AI strategies, as well as defense accelerators. A few examples of emerging national defense accelerators within NATO include but are not limited to: the British Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA), the Portuguese Department of Innovation and Transformation (DIT), the Spanish Centre for the Development of Industrial Technology (CDTI), the French Defense Innovation Agency (AID), the Leonardo-funded Italian Business Innovation Factory (BIF), and the nascent German Accelerator.

Beyond this, some nations have also created several multilateral frameworks, such as the French Canadian-led Global Partnership on AI, and the US-led AI Partnership for Defense, which bring together willing and capable nations to coordinate on certain issues or technologies. The trilateral partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the US (AUKUS), which was established in 2021, has talked of “accelerat[ing] respective defense innovation enterprises and learn[ing] from one another, including ways to more rapidly integrate commercial technologies to solve warfighting needs.” AUKUS has announced specific cooperation on AI, cyber, autonomous vehicles, quantum computing, and hypersonic capabilities moving forward. Each of these platforms are useful in their own right and could benefit from NATO and the EU joining to add their institutional weight. The risk with the current approach, however, is the rapid fragmentation of transatlantic efforts on EDT. If this trend continues, the result could be a diffused smattering of multilateral frameworks, each focused on a particular tech issue with a different small group of countries.

Despite this progress, much work remains to be done to ensure these new initiatives are effectively implemented, remain coordinated and largely complementary across several nations and institutions, and receive adequate resources, staffing, and empowerment. Otherwise, these efforts risk appearing as innovation theater — i.e., giving the appearance of innovation through rhetoric and surface-level efforts — as opposed to fundamental organizational change. What is desperately needed is a coordinated transatlantic strategy for competing in defense technologies.

In achieving this, part of the challenge for the Alliance is that transatlantic governments are no longer driving R&D spending for EDTs. For example, compared to the late 1980s, when US Department of Defense (DoD) R&D and business R&D were nearly equal, business R&D is now over four times greater (see graph). This has left DoD, and other governments of NATO member states, incapable of setting the pace for the private sector’s innovation priorities. By comparison, Russia and China, through their state-driven innovation efforts discussed above, have managed to mobilize the entirety of their military and civilian sectors and all elements of national power to set technological priorities and rapidly achieve key advancements. As a result, NATO has begun falling behind in key emerging technology areas.

As Allied governments work to regain their collective advantage over Russia and China, there are two, multi-faceted challenges in developing a transatlantic approach for defense technology.

First, NATO and EU member states are each focused on somewhat different technologies, while innovating and investing at radically different levels and speeds, with no central authority or coordinating function for all relevant stakeholders. To remedy this, NATO and the EU have worked to align their members’ tech priorities, with each organization outlining their overarching focus areas. NATO’s include AI, data and computing, autonomy, quantum-enabled technologies, biotechnology and human enhancements, hypersonic technologies, space, novel materials and manufacturing, and energy and propulsion. The EU’s key enabling technologies include advanced manufacturing, advanced materials, life-science technologies, micro/nano-electronics, and photonics, AI, and security and connectivity. The differences between these lists are understandable due the different core missions of NATO and EU. However, both should look for synergy to collaborate on common technologies of interest.

Beyond this, various Euro-Atlantic states have their own priority technologies lists catering to differing national needs, some of which overlap with the NATO and EU lists, as well as with the lists of other nations. The creation of these lists, even if not completely identical, is an important step that illustrates political will among allies to work together on defense innovation. Nevertheless, because there is no central political, financial, or legal authority to fully harmonize and enforce a focused, single set of shared priorities across all these actors, the result is by and large a patchwork of broad defense innovation efforts.

Adding to this lack of a single shared list is the reality that nations are innovating at drastically different levels and speeds based on budgets, talent, industrial and legal capacities, economic interests (which are often competing), and the maturity of each national innovation ecosystem. For instance, according to European Union (EU) innovation scores, Denmark performs 20% higher than the EU average, while Bulgaria performs well below 50%. These scores are based on ten key dimensions that provide a comparative assessment of research and innovation performance across EU members, the majority of which are also NATO Allies. The discrepancies revealed in this assessment underscore the difficulty in establishing shared defense tech priorities and getting allies to direct similar levels of resources in the same direction.

This is why NATO and the EU have established several common funds and other mechanisms to pool resources in pursuit of shared defense tech projects. However, even when countries channel proportionate resources toward similar technologies, they may not necessarily focus on the same use cases, which further slows progress. This is particularly relevant across autonomous systems and space capabilities, where allies have developed new hardware for different use cases, and where they could have leveraged common platforms or buses. In short, while the Alliance may have a general list of some commonly prioritized technologies, it still lacks sufficient shared technology goals, desired end states, and specific common use cases (like those proposed as part of the 2021 NATO AI Strategy), as well as a way to enforce and implement them.

Second, Euro-Atlantic allies diverge, most severely between the United States and Europe, on key policy issues surrounding the defense application of EDTs, such as technology governance, data-sharing, and supply-chain issues. The lack of a common policy framework impedes the Alliance’s ability to ideate, develop, and deploy defense technologies quickly enough to compete with Russia and China. Further, export controls (such as International Traffic in Arms Regulation) and data and hardware restrictions among allies prevent the development of a coherent, streamlined allied defense industrial base. These dynamics thus erode internal cohesion inside NATO and the EU and prevent the Alliance from setting a clear path to elevate its strategic edge. Additionally, it results in duplication of effort across the Alliance.

In an environment of strategic competition, transatlantic defense investment must do far more to reduce duplication and maximize return on investment (ROI). Although steps taken by NATO to develop a common strategic approach is a great step forward, more is needed to bring coherence to allied efforts. A more comprehensive common framework to assess, prioritize, enable, and accelerate the development and deployment of EDTs is needed to ensure NATO achieves greater progress in the development and fielding of these technologies to strengthen deterrence and defense. Without this, the Alliance may end up fighting the last war rather than the next one.

IV. Priority Technologies

The Need for a Replicable Prioritization Framework

As mentioned above, NATO, the EU, and their member nations have made progress in identifying common defense tech priorities. However, to further refine these into a more focused set of specific shared goals and provide compelling data to help enforce these priorities across allied nations, this study has developed an EDT Innovation Matrix. The EDT Innovation Matrix is a five-factor graph to assign a holistic prioritization level to individual EDTs. The Matrix assesses technologies based on five key factors: the time it will take to develop the technology, the immediate need for the technology, an educated estimation of cost, presumed policy challenges to development and implementation, and the transformative potential of each EDT. This approach ensures that EDTs are examined through a similar lens and works to prevent recency bias.

This is a tool that can be used by NATO and the EU to identify and rank priority technologies for the institutions, but nations can also use it to determine where their national priorities converge and diverge with multinational focus areas. The Matrix allows for concrete quantitative analysis of EDTs, which can help institutions and nations align perspectives and build consensus around tech priorities. This framework can also help nascent bodies such as the NATO Innovation Fund and DIANA chart their strategic direction and develop project selection criteria.

Importantly, the EDT Innovation Matrix is not just a static ranking of current technologies. Rather, it provides a replicable framework for allies to assess and balance future tech priorities. For example, as new technology suites – particularly those centered around AI – come online, the Matrix can act as a basic framework to conceptualize future strategies and prioritization across the Alliance. The EDT Innovation Matrix can help ensure that the Alliance’s EDT strategy and priorities remain relevant as the threat environment and technological landscape rapidly evolves.

The EDT Innovation Matrix below uses five variables, coded qualitatively and quantitatively by way of a cross-sectional literature review of the following:

- Time: How long it will take to develop and deploy a technology (low, medium, high).

- Need: Whether that technology: (a) meets a current met need (b) meets a current unmet need, or (c) meets a future capability need for the Alliance, compared to Russia and China in the threat environment and current landscape.

- Impact: The potential for the EDT to act as a core solution (existing solution to an existing problem) with relatively low risk and generating low impact, an adjacent solution (existing solution to a new challenge) possessing medium risk and producing medium impact, or a truly transformational solution (new solution, new challenge) with high risk and potential for high impact.

- Cost: Whether it will take a limited, medium, or a significant amount of capital to develop, deploy, and sustain the technology in question.

- Policy Challenges: Whether there are limited, medium, or significant policy barriers associated with the technology’s realization.

Candidate Technologies

To demonstrate the utility of the framework and exemplify the EDT Innovation Matrix, this study selected and ranked five technologies that can give the Alliance the most strategic ROI and elevate its competitive edge.

This assessment was scoped to focus on EDTs that are principally dual use in nature, in line with NATO’s current list of priorities. Least understood and most contested within the Alliance (with respect to how they can be deployed), dual-use technologies bring more value to governments due to their diverse applications and serve as key enablers for the Alliance across a wide spectrum of military and civilian capabilities. They are also easier to fund, from both government and private-sector sources, given their broader commercial potential. While this study focuses on the military applications of these technologies, these attributes make dual-use technologies particularly attractive and practical as priorities for the Alliance. This assessment also focused on technologies with near-term military application timelines (i.e., currently deployed or will likely be deployed within five years), which are most relevant for immediate NATO planning and require urgent attention.

Within these parameters, this study identified the following five technologies as key priorities for the Alliance: space-enabled capabilities, unmanned systems, hypersonics, edge computing, and cognitive influence capabilities. These were selected due to their relative need, feasibility (based on required time, cost, and policy barriers), and potential for transformative impact on the Alliance’s overall capability vis-à-vis Russia and China in future warfare.

1. Space-Enabled Capabilities

Space-enabled capabilities such as geospatial intelligence, GPS, and satellite communications, provide better, more real-time intelligence to decision-makers. They also enable military headquarters to effectively manage battlespaces and constitute the core capability connecting platforms and warfighters across the globe. In recent years, the use of these capabilities has proliferated across the defense, commercial, and civil arenas. In turn, NATO’s dependence on these capabilities, both as enablers and core technologies, has drastically increased.

The establishment of space forces across adversaries and allies over the last decade is a key contributor to this, along with the growing democratization of these technologies, which were previously only under the purview of major state actors. More players mean more risks for the Alliance, which has become accustomed to having the upper hand in the space domain. Exacerbating the challenge is the growing ability of commercial tools to replicate national defense capabilities – a phenomenon that will only accelerate with the broader space market predicted to exceed $1 trillion by 2038. At the same time, Russia and China are leading new efforts to develop and employ space capabilities apart from NATO-driven international space arrangements, and have demonstrated their ability to manipulate commercial activities for their own geopolitical gain.

Russia and China have different capabilities and legacy technologies, but similar aims. First, they have recognized space as a warfighting domain longer than the US or NATO and, thus, believe space is critical to their own future operations and broader great power competition. Beyond that, both have also learned that while the US and NATO were able to dominate key warfighting domains during the West’s global war on terror, the vast majority of their capabilities rely on access and freedom to act in space. Russia and China would like to dominate space, but in the near term, their aims are focused on the ability to mitigate the West’s positioning. Further, if tensions escalate, they want to be able to readily disrupt tools, such as GPS and satellite communications, which NATO relies on to pursue operations. US forces have detected evidence of Russia using local GPS jamming during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It is yet to affect their operations but it is unknown what the effects have been on local forces on the ground.

2. Unmanned Systems

Unmanned systems (UxS) have traditionally been key sources of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, while more recently providing the ability to directly strike targets. They provide this capability at an order of magnitude with lower cost than manned aerial assets while minimizing risk to pilots’ lives. This makes them attractive in terms of feasibility and impact, especially to Russia and China which rely on these asymmetric, low-cost tools to upend NATO and US high-end capabilities. Their use is increasingly transformative, as they have had a significant force-multiplying effect when paired with other assets. This was evidenced in the recent Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which showcased new applications of drones with which Allies are still grappling.

Unmanned aerial vehicle’s (UAVs) have played a significant role in Ukraine’s fight against Russia, with Ukrainian forces aiming to build an “army of drones” that will allow for constant monitoring of the frontline. This is coupled with the thousands of commercial drones that are used for real-time battlefield intelligence. UxS, particularly unmanned aerial systems (UAS), also have several valuable civil and commercial uses, including delivering packages and supplies and transporting critical medical aid, which can support allied civilians and militaries. This adds to their appeal as low-cost, low-risk, high-reward capabilities.

The need for NATO to harness these capabilities is rising, especially as UxS continue to evolve and gain new and enhanced features as individual platforms, swarms, and augmentation to existing operations. Beyond UAS, unmanned surface vehicles, unmanned underwater vehicles, and unmanned ground vehicles are coming online across the world with relatively short timelines. Many of these also have commercial uses similar to UAS and will benefit from significant revenue growth from the private sector, from retail customers to power companies. While some doctrinal and regulatory issues have yet to be addressed, there are already some policy initiatives underway for UxS, which can facilitate quicker adoption. As these capabilities continue to shape the competitive space, whoever harnesses them quickest and most effectively will have an important advantage, especially on the side of counter-UxS.

3. Hypersonics

Hypersonics are game-changing due to their ability to impact decision-making and mitigate adversaries’ capability advantages. At their core, hypersonic weapons are high-speed weapons that allow for a combination of greater maneuverability, range, survivability, and transformative responses. As they mature, these weapons will be able to render even current state-of-the-art defense systems largely ineffective. Hypersonics have the potential to shift the global balance of power and transform the existing capability gap between NATO and near-peer competitors, as well as potential emerging powers. Furthermore, hypersonic propulsion systems developed by the military could be adapted to meet civil and commercial needs for space capabilities or even commercial transport. This increases their overall strategic value.

The forthcoming generation of hypersonic weapons will drastically shorten decision and reaction times at both tactical and strategic levels. Compared to traditional intercontinental ballistic missiles and cruise missiles, hypersonics combine speed exceeding that of intercontinental ballistic missiles, along with the high-end maneuverability of a cruise missile. If used by adversaries, these two factors can mitigate the US’s and NATO’s capability advantage in areas such as its blue-water navy, overseas bases, and associated power projection.

Because next-generation hypersonics do not need to travel a straight line to their targets, they are harder to defeat once airborne. They exacerbate the risk or increase the likelihood of success of high-impact events, particularly decapitation strikes, as their trajectory – unlike ballistic trajectories – cannot be predicted. There is an urgent need for developing defense capabilities for hypersonic weapons. Further, it is difficult to determine who fired them, which also makes it challenging to deter or retaliate against a hypersonic attack. This increases the risk of miscalculation and unintended escalation, underscoring the need for NATO to focus on these capabilities.

4. Edge Computers

Edge computing brings mobile computing and data processing solutions to the network’s edge, where the users and devices are located in the field. Because this data does not have to travel back to a center to be processed, it enables faster analysis and more timely and relevant insights. Edge computing has high-impact effects on issues spanning homeland security, civil emergency response, crisis management, and multi-domain military operations which make it extremely valuable to the Alliance’s wide range of activities. In the latter case, it has enormous benefits for militaries, supporting more seamless joint command and control (C2), connecting sensors to shooters, enhancing situational awareness, providing real-time data to personnel in the field, and enabling rapid response.

Edge computing also provides a foundation to empower lower-level commanders to make decisions in time-sensitive situations, particularly where decision speed is critical. As reach back cannot be guaranteed in today’s contested environment, flattening the “sensor to shooter” architecture and pushing data forward is a game changer. The results of this will have a profound impact on the way NATO fights and reacts to conflict and pre-conflict scenarios. These capabilities also provide the foundation for multi-domain operations, which is the future framework for US and NATO operations.

Edge computing systems are quickly becoming more available at lower costs, in part to keep up with commercial and industrial needs. They are in turn becoming more integral to military activities, underscoring the need for the Alliance to keep up. Disagreements over data-sharing, privacy, and intellectual property regulation will inhibit the rapid adoption of edge technologies at the transatlantic level. However, the need may outpace the policy challenges. The ability to generate insights and rapid response at both the tactical and strategic levels is critical to winning the next fight. Edge computing could be a key enabling capability for NATO’s intent to strengthen deterrence and defense, especially forward presence in the East, announced at the Madrid Summit. Without the capabilities edge computing brings, NATO would be left operating on a Cold War hub-and-spoke model that cannot keep up with the changing character of warfare.

5. Cognitive Influence Capabilities

Cognitive influence capabilities combine information warfare and cyber tools to target a population to alter how they think, and consequently, how they act. The ability to manipulate foreign societies from within and quietly infiltrate their leaders’ decision-making processes can determine the result of hostilities before they ever conventionally start. In today’s hyper-connected world of individual devices, apps, and myriad media sources, it has never been easier to influence public opinion, elections, information flows, and even behavior inside adversary countries. Already, Russia and China have actively used cyber espionage, data hack-and-release tactics, disinformation, psychological operations, and similar tools against the transatlantic community, creating pervasive threats that fall below NATO’s traditional threshold of armed conflict and impede swift response. These methods provide a low-cost, relatively quick option with high impact. For example, they allow Russia and China to destabilize NATO from within without ever firing a shot. This is the Alliance’s greatest shortfall, and a key vulnerability affecting strategic competition with Russia and China.

As adversaries continue to push the limits of these capabilities, NATO must develop cognitive influence superiority. In the Cold War, NATO maintained a robust set of cognitive influence capabilities, which it subsequently lost as great power competition subsided. As technology has advanced in the cyber and information domains, the Alliance must urgently relearn how to take back the initiative and rebuild an innovative toolbox to shape its adversaries’ mindsets. The policy challenge for Allies will be to develop and deploy these tools in a way that is consistent with NATO’s shared values and principles such as human rights and the rule of law. As has been clearly demonstrated in Russia’s recent full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the ability to win the war of hearts and minds will be at the center of any future conflict.

EDT Innovation Matrix

The five selected technologies were assessed within the stated parameters. A demonstration of the replicable EDT Innovation Matrix may be seen below. Both visuals provide alternative ways in which the assessment can be presented.

For a chosen EDT, an assessment is made using the five variables identified. 1) Time: Low, Medium, High; 2) Need: Met, Unmet, Future; 3) Impact: Core, Adjacent, Transformational; 4) Cost: Limited, Medium, Significant; 5) Policy Challenge: Limited, Medium, Significant. The five colors represent the level of challenge regarding that specific variable. The colors can be seen as a visual representation of a scale of 1-5 (1= dark green and 5 = red).

It must be noted that the color is a distinct assessment from the word. For example, although unmanned systems (UAS) meet a current need, it is coded as red because there are significant gaps within UAS such as the lack of effective counter-UAS systems and operating ability in denied environments.

In the chart format each of the five variables of the EDT Innovation Matrix are represented visually. 1) Time and 2) Need are shown on the axes, and 3) Impact is on the background of the chart. The 4) Cost is represented by the size of the circle and 5) Policy Challenges is represented by the color of the circle.

Excluded Technologies

A key technology excluded from this assessment is machine learning (ML) as a subset of artificial intelligence (AI). AI and ML capabilities hold transformative potential for expanding knowledge, increasing prosperity, enhancing security, and enriching the human experience. This technology will be a source of enormous power for countries that harness them, fueling competition between governments and companies racing to employ them for strategic ambitions. However, as governments have placed an increasing emphasis on the development and adoption of AI, including for security and defense, a vast new body of literature has emerged on these technologies.

Policy discussions on the security applications of AI and ML have become commonplace across Washington, DC; Brussels; and Allied capitals, and national strategies for AI have already been released. As a shared understanding of these issues grows, the research team decided not to focus on AI/ML as a technological priority in isolation, but rather as an enabling technology present across virtually all emerging technology suites, including the five outlined above.

Other key technologies excluded from this particular assessment that could be prioritized in the slightly longer term include quantum-enabled technologies, synthetic training environments, CRISPR-enabled biological warfare, strategically effective cyberattacks, civil information integration (e.g. smartphones used for targeting in Ukraine), and directed energy, among others.

V. Toward a Transatlantic Policy Framework for Defense Tech Cooperation

Perhaps even more important than identifying common transatlantic technological priorities is the need to develop a shared policy framework to act upon these priorities. NATO, the EU, individual nations, and industry leaders all have unique roles to play in helping the Alliance more effectively harness emerging technologies for its own defense, deterrence, and strategic advantages. However, one critical element is missing: a shared transatlantic policy framework to help align actions across all these stakeholders. Such a policy framework would provide a common lens through which NATO, the EU, and their member nations can conceive, discuss, coordinate, and implement all efforts to enhance the Alliance’s technological edge. This blueprint would serve as a basis for stronger cooperation with industry practitioners – who are the key drivers of innovation – as well as stronger coordination with other like-minded nations outside the Euro-Atlantic area, including those in the Indo-Pacific. Such coordination will be critical for competing against China’s technological rise.

As with all policy frameworks, they are only as valuable as their implementation. The authors recommend developing an accompanying roadmap with key performance indicators (KPIs) to help measure the progress and implementation of the recommendations. An initial idea is provided in Appendix 1.

Policy Pillars and Recommendations

The following core pillars should serve as the foundation for this transatlantic policy framework for defense tech cooperation:

1. Forge a Common Assessment of the Technology Competition

While most Euro-Atlantic governments and institutions acknowledge the importance of investing in defense tech, differing views on how to approach Russia and China drive disparate budgetary priorities, policy development, and levels of political will to act. To harmonize collective efforts, Euro-Atlantic allies and partners need a deeper, shared threat assessment of the tech competition. This would also provide a basis to cooperate with like-minded partners outside NATO and the EU. To be more proactive, allies and partners must shift their mindset away from examining tech threats and toward exploring tech opportunities. The Alliance cannot afford to be reactive, waiting to see how Russia, China, or other actors may weaponize emerging technologies. Instead, it must shape the competition and anticipate future needs to stay ahead of the curve.

Recommendations:

- EU member states and Allies must utilize the EU Strategic Compass and NATO Strategic Concept as starting points to develop a shared understanding and assessment of the tech competition and create a sense of urgency for policymakers to act. Russia’s war in Ukraine should be a stark reminder of the need for the Alliance to compete and win across all domains and the imperative to invest early in the right capabilities.

- The US and EU should use their ongoing dialogue on security and defense to align approaches to Russia and China. This should include candid discussions and evaluations of each actor’s strategic aims, technological capabilities, doctrine, exercises, recent activities, and associated policies.

- NATO should leverage its political guidance and Defence Planning Process to encourage a forward-looking approach to defense tech investment. Empower the Conference of National Armaments Directors (CNAD) and the Science and Technology Organization (STO) to drive capability development priorities that push the Alliance to create strategic dilemmas for its competitors, not just respond to current threats.

- Based on a shared threat assessment of the tech competition, NATO must adapt its doctrine, training, and warfighting techniques, drawing on the NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept managed by NATO Allied Command Transformation and led by the Military Committee. These efforts must be mainstreamed across the Alliance to create a common intelligence and operational picture of the strategic environment.

2. Facilitate Faster Adoption of Technology

Many Euro-Atlantic nations and institutions have their own lists of priority technologies and nascent tech strategies, some of which overlap with each other. However, many of these plans are too focused on the technologies themselves (i.e., investing in AI because it is important), as opposed to the desired effect (i.e., what exactly the AI will be used for). If transatlantic entities channel their efforts into solving a few specific collective problems with tech, they could better align R&D funds and maximize results. Tying innovation projects to specific use cases and direct paths to production contracts would facilitate faster adoption of technology. This requires a shift in focus from individual technologies to a more holistic focus on desired capabilities and outcomes. While an over-emphasis on use cases can constrain innovation in the private sector, this approach can be effective for multilateral cooperation.

Recommendations:

- Nations must avoid stocking the shelves with “technology for technology’s sake” by focusing on specific desired effects. Allies should agree to work on three to five key use cases for each of NATO’s nine priority technologies and develop, procure, and deploy based on that.

- NATO, the EU, and member nations should focus funding on supporting procurement and adoption, as opposed to strictly R&D. For example, the majority of the European Defense Fund (EDF) goes toward development, and there is limited follow-up to get nations to buy capabilities that have been created. Adoption-dedicated funding initiatives would help address the “valley of death” between concept and production. The recently endorsed NATO Innovation Fund should consider how to promote Allies’ procurement and adoption of capabilities proven feasible and promising through successful R&D efforts.

3. Improve the Regulatory Environment

Despite the stated desire to increase transatlantic tech cooperation, many governments have failed to sufficiently adjust the regulatory environment to better facilitate such collaboration. Major legislative barriers such as International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which governs export controls and tech transfer, as well as complex, slow-moving contracting processes hinder innovation. They impede multinational collaboration, complicate intellectual property (IP) management, and make it costly and time-intensive for the industry to do business with governments. The current regulatory environment not only reflects a general distrust of industry, it also underscores the ongoing competition for economic interests among transatlantic nations over industrial base issues. This is particularly the case with private businesses that seek a profit to advance the interests of the nation, also known as “national champions,” many of which are still owned in part by various European governments. A greater sense of urgency among nations to put the long-term collective good of the alliance above short-term economic gains would help find ways to relax or work around legislative barriers that impede allied interests in the tech competition with Russia and China.

Another regulatory priority is the need to establish shared transatlantic principles to govern how defense and dual-use tech is deployed, in order to shape the rules of the road before Russia and China do so. A lack of shared transatlantic principles to govern EDTs will have a direct impact on collaborative innovation, interoperability, and the ability to create a unified value proposition for a democratic technology model to compete with the authoritarian model of Russia and China.

Recommendations:

- The US ought to strengthen its defense industrial base by opening it to more close, trusted allies. At the same time, European nations must reduce protectionist policies which favor “national champions” at the expense of both domestic startups and allied nations. Leveraging NATO and the EU’s collective technological expertise requires a ‘best in breed’ approach, not a best of political backing.

- The US and EU could catalyze a new dialogue on export controls through the US-EU Tech and Trade Council, with NATO involved, to reduce barriers to multinational tech cooperation. This could involve creating a transatlantic tech access clearing center focused on dual-use exports, tech transfer, research protection, and creating a shared certification system for trustworthy vendors (e.g., if a company gets verified to work with one member nation, they would be automatically certified through this system to work with other NATO and EU members). Lessons should be drawn from the tech-sharing aspects of AUKUS which established tri-lateral cooperation on AI, cyber and quantum computing, hypersonic capabilities, and information sharing to examine if these mechanisms can be applied to other international frameworks.

- For companies from trusted NATO Allies, the US should streamline the process for establishing a proxy board, which is required for foreign tech companies to do business in the US through a US holding. This would open the door to new companies offering innovative capabilities.

- The US should create a corps of top tech talent (US citizens) who may maintain their security clearances even if they leave government or classified contracts. Currently, clearances are difficult to gain sponsorship for and often go inactive shortly after an individual leaves government service or stops supporting the classified contract to which they are attached. This cadre model would ensure experienced tech experts can support classified work on a short-term basis or with limited notice, rather than having to go through lengthy (often a year or longer) hiring and/or security clearance processes. This would make it easier for key personnel to transfer across public and private sector positions without having to go through a new (re)investigation, an onerous process that stifles the mobility of tech talent.

- Euro-Atlantic nations should make it more difficult for Russia and China to access Western commercial tech (through legal and illegal means), which they can manipulate for military and security purposes. This would involve deeper coordination to tighten export controls, foreign investment screening, foreign research partnerships, etc.

- Europe and the US need to work together to offset major defense tech supply chain vulnerabilities created by economic dependence, particularly in manufacturing and semiconductors, on China. Allies should coordinate to illuminate vulnerabilities and develop legislation and common approaches to promote chain resilience, transparency, and security of supply, particularly for micro technologies and rare earth materials. Examples of this would include developing a transatlantic open-source intelligence database that identifies and tracks investors and companies with links to the Chinese state or state-backed enterprises. To make this most impactful, the analytic frameworks and tools should be deployed via an expert cadre using a training-of-trainers methodology.

- which could be done at the working level under the next Joint Declaration on NATO-EU Cooperation. Furthermore, these principles must be developed with input from other relevant bodies such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and United Nations (UN). Guiding principles for defense technology use and deployment could include proportionality, lethality/precision, reciprocity, verification, and the human element of tech. These can build on what already exists in the industry, including NATO’s AI strategy, the EU’s digital strategies, etc.

4. Incorporate Nontraditional Partners to Inspire Radical Innovation

Current government procurement and innovation cycles tend to favor large traditional defense companies, or “primes,” which have the knowledge, experience, and capital to navigate lengthy and complex contracting procedures. This makes it difficult for new players, such as start-ups driving radical innovation, to break in. Bureaucracies are often naturally risk-averse and hesitant to work with nontraditional players which can be more volatile. Yet there is a longer-term risk in not exploring these options, specifically that without them, Western governments could be left behind. To stimulate real innovation, governments must make big bets, embrace failure as an option, and commit to engaging these partners, especially those housing dual-use technologies outside of the defense realm. Pushing start-ups to be sub-contractors under primes does not always create mutually beneficial arrangements, therefore governments should also provide more agile contract models for nontraditional companies.

Recommendations:

- Rather than prescribing a solution and over-specifying requirements, governments should present a challenge to industry and academia with competitions and let them develop a wide range of possible solutions. Governments should also allocate funding to these competitions in a manner similar to the XPRIZE Foundation’s approach and NavalX and DARPA hackathons.Government support would encourage investors to innovate around competitions using their own independent research and development (IRAD) and allow different kinds of players to participate.

- Competitions and early awards must be linked to funds for procurement. They should also have clear pathways to transition to full contracts. To encourage scaling and further production opportunities, governments could establish an incentive program in which, if a new capability succeeds beyond the first procurement to a second customer, the first is paid back or rewarded monetarily for taking the initial risk.

- Euro-Atlantic governments should also convince more venture capital (VC) firms to invest in defense startups, recognizing the returns will not be immediate but can have major long-term payoffs. VCs should be able to contribute to and beef up early awards from governments, where they see opportunities for scaling between prototyping and production (see RDER Fund as an example). At the same time, governments should provide more matching of VC funds for smaller companies and convertible loans and grants.

- Governments should utilize more agile contract models that have quicker award timelines, more money upfront, and more flexible milestones for evaluating progress and measuring deliverables, especially to accommodate start-ups.

- One mechanism for doing this is the US’s Other Transaction Authority (OTA), which should be backed up with more funding. Other options include using more small business research grants which have shorter phases and quicker transitions to higher resource levels. The NavalX Tech Bridges is a model that can be adopted by NATO and the EU. This model provides Small Business Innovation Research grants (SBIRS) to start-ups without the means to break into the defense industry.

- More flexible contracts should also be utilized in government-to-government R&D partnerships, which often require fully fledged concepts that require lengthy approvals in advance. This not only constrains innovation by over-prescribing the methods and final product but also disincentivizes multinational tech collaboration. Instead, governments should use memoranda of understanding (MOUs) which allow the participating organizations and companies something closer to “carte blanche,” where they get to decide how best to achieve the objective presented. The US DoD Defense Innovation Unit provides a good example of a possible model that allows for this flexibility.

- Governments and military services should look to national special operations forces for more flexible models for engaging with the tech industry.

- As part of more flexible contracts, governments should find ways to lease intellectual property associated with new tech, as opposed to needing to buy it outright. Because IP is often the only profitable asset start-ups can claim, this is a disincentive for them to do business with governments.

- Governments should make it easier for their contracting officers to take risks on new companies and nontraditional players. One way to do this is to create a specific category of awards for nontraditional companies which are capped at a certain value to minimize risk for the program manager if the project fails.

- Large companies or primes should offer more programs for nontraditional players (with whom they often partner or subcontract) in which they offer to hold their security clearances, provide workspaces, and give tutoring for navigating government contracting, without onerous terms for the startups.

- The EU should provide a platform for small, innovative companies to demonstrate their technologies to multiple countries at the same time. This would provide new opportunities and visibility for start-ups who do not have the resources and capacity to travel to each individual country to do demos and pitch their capability several times.

- The US and larger European countries should explore lessons learned from small countries such as Latvia and Estonia who have never had massive traditional defense primes. As governments, they work directly with start-ups and nontraditional organizations striving to create new legal and contracting mechanisms that comply with EU-level legislation. These practices could be applied elsewhere across the transatlantic community.

- Nontraditional players who have been through government contracting processes should collaborate on a book of best practices to help future start-ups. The NATO Industrial Advisory Group (NIAG) could offer to develop similar books of best practices on how to work with NATO procurement agencies, such as the NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA) and the NATO Supply and Procurement Agency (NSPA).

5. Continuously Scout for Tech Solutions and Talent