Beginning November 30, audiences at Washington’s Shakespeare Theatre Company—home to Ophelia, Cleopatra, and Desdemona—will hear from an entirely different sort of heroine: Britney Jean Spears.

More than six years in the making, the musical featuring her songs, Once Upon a One More Time—yes, that’s a nod to her breakout hit, “Baby One More Time”—began gestating at a moment when the teen-icon-turned-paparazzi-catastrophe was largely remembered as a bit of nostalgia from the early aughts. But as the show prepares for a global premiere in Washington, Spears is news once again, the subject of documentaries and court proceedings and at least two rallies at the Capitol. Even Bard-loving traditionalists might see a Spears-inspired tale as something that the theater’s Elizabethan namesake could have recognized as the stuff of great drama.

For the uninitiated: A 16-year-old when she debuted in pigtails and a skimpy school uniform, Britney fixated a generation of teen girls with her bubblegum pop and sexual confidence. But as her personal life spiraled, courts eventually subjected her to a conservatorship, a legal apparatus that put her father and others in charge of all her affairs, from her right to remove her own IUD to decisions about her $60-million estate. Spears’s pop-culture presence faded somewhat, right along with her contact with the outside world. Then, over the past year, bombshell reports from the courthouse revealed a much more disturbing reality than the public imagined—a story of a thirtysomething mother begging to be freed from a 13-year legal confinement.

In other words, it’s an unexpectedly perfect time for a husband/wife power-duo choreography team to open a down-with-the-patriarchy musical featuring the Britney songbook. The show is headed to Broadway, and if its producers’ hopes of landing a blockbuster pan out—Sony Pictures has already bought the film rights—Washingtonians who attended the DC premiere may have a more personal take: I SAW THE WORLD’S BUZZIEST SHOW BEFORE EVERYONE ELSE.

The production has survived one postponement, one cancellation, and the ups and downs of key personnel changes. But the legal drama of the last few years—the court ended Spears’s conservatorship on November 12, two weeks before opening night—also presents a significant marketing challenge: a newly enlarged universe of Britneyphiles who are attacking the play’s very existence, worrying that it’s just another profiteering venture by those she says exploited her.

If there’s one thing that hardcore Britneyologists recognize about their subject, it’s that she’s usually been the driving creative force of her work. That was true even of tours that took place during the conservatorship. As Spears sang in a 2008 number, the same year the court intervened, “I’m a put-on-a-show kind of girl . . . . I’m like the ringleader, I call the shots.” Given what we know now, though, the Britney fandom isn’t quite sure what to believe about the musical.

One day a few years ago, before the production was announced publicly, its playwright, Jon Hartmere, was fluttering around a theater in Midtown Manhattan, hyper-anxious to hear his lines spoken aloud. The band was warmed up, the actors seated in two semicircular rows onstage. Everybody was ready for the day’s big read-through, but a little nervous, too.

The audience was invitation-only and small—mostly family and friends. The lights dimmed, and then, like a silent-movie star, Britney Spears sauntered down the aisle to her seat, flanked by an entourage. Showtime.

“Britney was laughing and clapping along and singing.”

It was the spring of 2018, and the pop star had come to see the musical’s progress. Hartmere–who’s slender, blond, and partial to blue-rimmed glasses–was in a row behind her, “literally vibrating in my seat,” he recalls. He was trying to keep his attention on the actors, but his eyes kept turning to Spears, searching for her reaction. “She was laughing and clapping along and singing” throughout, says Hartmere. She approved.

The musical had been Britney’s idea from the start, says James Nederlander, president of the second-largest theater owner on Broadway, which produced Chicago, The Color Purple, and Kinky Boots. Three years earlier, he says, he got a call from Spears’s then-agent, Rob Light. Was there any chance Nederlander was interested in producing a musical with Britney Spears songs? “I almost went through the phone to LA and said, ‘Yes, sign me up,’ ” Nederlander recalls.

According to Nederlander—an exuberant, blunt-talking producer who took over the company from his father—Spears really wanted to see her hits paired with a story about princesses. The company that owns her music rights licensed her catalog, and Nederlander’s team got to work on the vision, ultimately choosing Hartmere’s proposal for its humor and sophistication. A stage and screen writer, Hartmere had made a splash with the rock musical Bare: A Pop Opera, about gay teens in Catholic school, but he also had another, less glamorous credit to lean on: He’d once taught elementary school and read fairy tales to his students. “Her catalog slotted into this [princess] idea kind of magically,” Hartmere says, adding: “It didn’t feel like we were really having to force anything—and that includes her biggest hits.”

Cinderella became the main character, and Hartmere’s guiding star. When he heard Britney’s “Work B-tch” (“You want a hot body? / You want a Bugatti? / You want a Maserati? / You better work, b-tch”), he could instantly see Cinderella’s “stepmother and stepsister singing to her.” He began pulling in princesses from other tales, threading together a feminist anthem ripe for the post-MeToo era—an era, it must be noted, very different from the one that first embraced Spears’s brand of pop.

The story is ingenious and improbably funny, one part fantasy, one part metaphor for the real Britney’s life, or that of any other woman victimized by a controlling man. Cinderella and her royal friends have grown up on Grimm stories, regularly revisiting each classic in their book club. Every time a child in the real world wants to hear one of the stories—Snow White, Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty—the royal has to act out her tale. (Onstage, a child actor sits to the side watching, Princess Bride–style.) These are working-girl princesses, that is. And they are burned out.

When Cinderella begins questioning her lot in life, the Original Fairy Godmother (they call her the O.F.G.) appears and hands the princess—what else?—The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan. The shell-shocked damsels realize, happy endings be damned, that it’s someone else who’s been scripting the story of their lives. Oh, baby, baby—cue the existential crises. A strike ensues, demonstrating that the entire male-led enterprise depends on . . . the second sex. Ultimately, Cinderella and her newborn posse of feminists defy a clueless Prince Charming, a conniving stepmother, and the show’s own furious narrator to seize the right—or in this case, the prop quill—to write their own stories from then on. Sound familiar?

The show contains 23 Spears hits. Among them are the must-have classics (“Toxic,” “Lucky”), the obvious show tunes (“Cinderella,” “Circus”), the deep cuts (“Passenger,” “From the Bottom of My Broken Heart”), and the mid-career sass tracks (“Piece of Me,” “Womanizer”). Hartmere did have to rewrite some lyrics to jibe with his story line, a process called relyricization and one he says he undertook with extra care. Earlier versions of the script leaned more on sultry Spears than kid-friendly Spears, but Hartmere made tweaks to strike a tone that might resonate with a broader age range (and sell more tickets). Songs have gone in and out. He slotted the playful “Clumsy,” then cut it, but kept a character by the same name. (Clumsy is Snow White’s eighth dwarf; he falls for a prince, a nod from Hartmere, who’s gay, to Britney’s huge gay fan base.) Spears’s team—including her manager at the time, Larry Rudolph—was involved along the way, attending developmental workshops and other readings and sharing feedback with the producers.

But as with all things Britney, it’s the dancing that’s as crucial as the music, right down to an unlikely twist for Broadway: hiring a pair of dancers to direct the entire show. Keone and Mari Madrid have never directed a musical before. Still, they have worked with Billie Eilish, BTS, and Kendrick Lamar and have assembled numbers for all the major dance-competition shows that have overtaken prime-time TV in the last decade. Nederlander initially enlisted them as Once’s choreographers. But in 2019, when he and his partners split with the show’s original director, they decided to promote the pair. “Talented as hell,” Nederlander says of the couple. “You gotta gamble a little bit in this business, too.”

Mari, who was very pregnant at the time, jokes that she was surprised she didn’t go into labor when she answered the call. “Everyone was reassuring and saying, like, ‘Hey, you know, Broadway wants something fresh, something new,’ ” Keone remembers, adding, “ ‘Don’t worry about being whatever you think Broadway is—we want you guys to be who you are.’ ”

Of course, the change meant significant revisions, and that meant a delay. The premiere date was now April 2020. Nederlander had wanted to open outside Manhattan—a common playbook for big-budget musicals; his company chose one of its Chicago stages. If all went well, the show was expected to land in New York soon after.

You know what happened next. Two weeks after rehearsals began in March 2020, Covid shut everything down. The cast sang one final song together, crying and embracing before scrambling to get home. They wouldn’t rehearse Once again for 19 months. By the time the Spears musical would be ready, the real-life Spears drama would reach peak intrigue.

But before we get to that, here’s something you may be wondering: Of all the cities in the country to open in, how did it come to be Washington? And of all the theaters in Washington, how did it come to be one dedicated to the Bard?

DC is something of an incubator for buzzy new musicals—Dear Evan Hansen, Mean Girls, and Beetlejuice opened here, too. The city has a reputation in drama circles as a good testing ground, in part for its smart audiences and proximity to New York. Yet Shakespeare Theatre has never hosted a pre-Broadway tryout of a new commercial musical, for reasons you’d expect: It’s best known for modern retellings of its namesake, or fresh takes on Greek epics. Classics are the core of its mission.

In 2019, though, the 35-year-old organization brought on a new artistic director for the first time since its founding: Simon Godwin, a brainy, provocative Brit who had become known for mounting invigorating productions of Shakespeare at the Bristol Old Vic, Britain’s National Theatre, and beyond. Shakespeare Theatre had been in the mix for Once before Godwin started, but schedules made it tricky and Chicago won out. Last winter, the theater reached out again. After the brutal economics of the pandemic, reopening with a Spears musical would be like jet-rocket fuel.

This time, Nederlander was all in—it didn’t matter that Godwin, the effusive, Cambridge-educated director, had never overseen a brand-new musical headed to Broadway. “I just trusted him,” Nederlander says, adding, “I thought that this could be a good match.”

In a way, the show is a coming-out for Godwin, too. Covid forced him to shutter the theater only seven months into his new role. At the time, he was overseeing James Baldwin’s lesser-known gospel musical, The Amen Corner—only the second show by a Black dramatist in the theater’s history. (The first was earlier in the same season—i.e., also under Godwin.) And at Christmastime before Covid, he had tried something new with Lauren Gunderson’s feminist reimagining of Peter Pan, which places Wendy at the center of the tale. A father of twin four-year-old girls, Godwin says he’s passionate about producing family-oriented shows during the holidays. At the time, some stalwarts bristled, questioning how a Disney story related to the Bard. Godwin understands the skepticism, but a “classic,” in his view, “doesn’t mean something that’s old—it means something that’s excellent.”

He’s getting a similar quizzical response now as people try to square the curious combo of Shakespeare and Spears. The way he sees it, a play that mashes up timeworn fairy tales with a she-hero of contemporary culture syncs completely with his institution’s mission. “We as a theater are interested, very concretely and very specifically, in retelling stories from the past in a present way,” Godwin says. “When I got to see the [Once] script, I thought, ‘Yeah, there’s something bold and audacious and irreverent and cheeky and larger than life about this material, which for me sits really easily with Shakespeare.’ ”

The money would be nice, too. Godwin had to lay off 38 staffers during Covid. Even before that, the theater, like many stages, was worrying about ways to reel in younger, more diverse audiences. Once could be a game-changer: The theater stands to pocket a percentage of the musical’s future box-office profits on Broadway. The arrangement is much like the Hamilton agreement that, six years after that musical’s debut, is still flooding money into the Public Theater, the off-Broadway spot where it opened before moving to the Richard Rodgers Theatre. Once could likewise ensure the organization’s livelihood for years to come. Ticket subscriptions to Shakespeare’s 2021–22 season are filled with newcomers compared with 2019–20; early sales of Once were so strong that the theater is considering an extension. The box office upped its top price: Typically, tickets run less than $120, but a Once seat can cost $190.

Over a five-week run in a house with a 755-seat capacity, those Washington audiences will add up. They’ll also be instrumental in the show’s development. Live theater is malleable, so if one laugh line meets awkward silence, for instance, it might be cut. Tryouts are “absolutely a study of the science of the audience,” says Godwin, adding, “Our world is changing so quickly, a script or a joke or a comment that would have meant one thing a year ago could mean something slightly different today.” Are people singing along, on the edge of their seats awaiting the next number, or are they distracted, bored?

Godwin told me recently he’s optimistic the show does justice to what he calls Spears’s “provocation”—her idea. “I’m hoping that she’ll come and see the show in Washington,” he said. “Wouldn’t that be wonderful?”

One Saturday in late October, I took the elevator to the ninth floor of New 42 Studios in Times Square to see, at last, how Once was coming together. It was six weeks until showtime, and rehearsals had just begun. (The popular New York studio building hosts dozens of productions in development. The Once team would travel to DC in mid-November.)

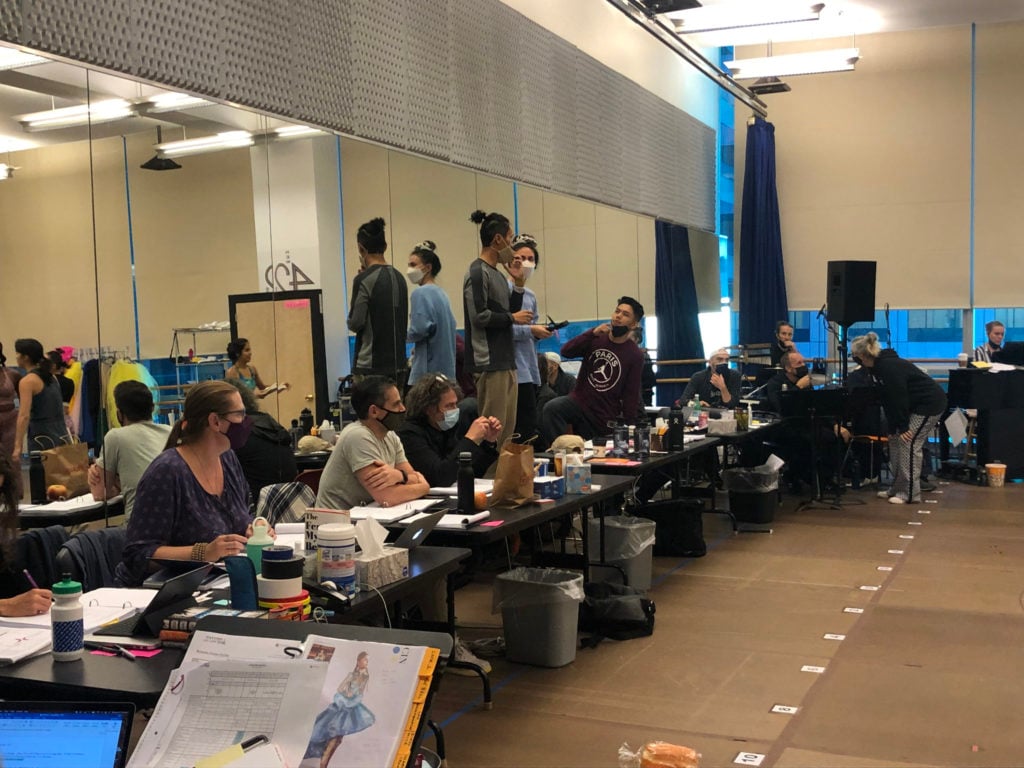

By the time I arrived, 22 actors—all in sweats, tights, and various versions of athleisure—had been at it for hours, hitting moves and hustling to find the next mark. Start, stop, again.

Justin Guarini, of American Idol fame, who plays the vapid, pretty-boy Prince Charming, was working on a scene, script pages in hand, in which Cinderella (played by Great News star Briga Heelan) and Snow White (Broadway darling Aisha Jackson) have just discovered that their “one” true loves are actually the same person: Charming’s been playing them. Caught and flustered, Guarini struck a dramatic pose to start “Oops . . . I Did It Again.” (Later, the princesses will find him climbing down Rapunzel’s tower, sing “Womanizer,” and throw him into a well LOL.)

The room had a corner for the drum kit and piano, props, and colorful tulle skirts, in place of the elaborate costumes to come. The cast faced a mirror wall and a line of tables littered with binders, sodas, and face masks: the Madrids, Hartmere, and creative consultant David Leveaux at their command center. In one sense, it was all pretty familiar: This was the same building where they’d rehearsed in 2020. But that’s not to say it felt the same. A block away, an LED billboard was flashing Britney Spears’s face: an ad for Netflix’s Britney vs. Spears documentary about the conservatorship.

Over the previous four months, Spears had finally been allowed to speak to the court in a public hearing. She’d delivered damning testimony that painted her father, Jamie, as a cruel egomaniac who overworked and overmedicated her. Public outrage swelled. Jamie resigned as her conservator and asked to end the 13-year arrangement completely.

“The show is about starting over, writing your own stories.”

I had wondered if the turn of events would mean a few more changes to the show, but Hartmere told me they didn’t have to tinker with anything. “I don’t know whether that’s just because we’re so far away from what’s going on or if it’s just happenstance, but there really hasn’t been an ‘Oh, we gotta pull that’ moment,” he says. The musical-makers have followed the Britney news, but in interviews with me, they also distanced themselves from it. When I’d ask people if they felt conflicted about being part of the production, they’d point out Spears’s connection to the show—that she was in it from the very beginning. It was her idea. She adores princesses. She saw a read-through and loved it. “The show showcases how brilliant her music is and what a real superstar she is. . . . It’s about starting over, and writing your own stories,” Hartmere told me.

“Look,” Guarini says, “I just want Britney to have the outcome that she desires for her life from this situation, period.”

But as with all Britneyana in the year 2021, it gets complicated. How should we—the folks who might spend $190 on a ticket—feel about everything?

Some facts are not good: The idea surfaced in 2015, seven years into the conservatorship. The deal materialized during a time when Spears had no say in her business dealings. But other details would seem to offer a green light: Over the years, Spears has gushed about fairy tales on Instagram, posting princess memes and naming her favorite (it’s the main character of “The Princess and the Pea,” who happens to be in Once, too). In 2019, when the play was announced, this is what she said: “I’m so excited to have a musical with my songs—especially one that takes place in such a magical world filled with characters I grew up on. This is a dream come true for me!”

And yet: The comment came not on her Instagram but in the form of a statement provided to the press. Was it truly how she felt? Can we feel secure in believing this was all part of her plan, given what we’ve learned about trusting those who said they spoke for Spears?

And who stands to benefit if the play is a wild success? Deadline Hollywood reported in 2019 that Spears’s then-manager Larry Rudolph would executive-produce the musical’s eventual film with her. In her testimony to the court, she described feeling intimidated and punished by “my management” during the time she alleged she was overworked; she did not name Rudolph, and has had several managers. Britney stans have been grappling with whether the price of admission to Once would fill the pockets of people Britney has alleged oppressed her. The particulars of the contract and the royalties are not public.

If you’re a Spears defender, there’s a lot you don’t know. So it’s inevitable that, for some, it might just feel too soon, too . . . icky.

“Come on, it’s entertainment, please—we’ve been locked up for a year and a half. Enjoy yourself,” James Nederlander told me in September when I asked if he was ruffled by this vein of critiques. What did he think of those who are concerned that her conservators might profit? “I never heard any of that,” he said. “Hopefully, there will be a lot of profits for everybody.”

Maybe none of these questions have easy answers, but they do expose an uncomfortable truth. One way or the other, we’ve been buying tickets to The Britney Show for the last 15 years. We watched as the conservatorship began and trusted that Daddy knew best—she was out of control, she needed help, didn’t you see her shave her head? Then Jamie organized a world tour and a Vegas residency, and the old Britney showed up, the megawatt performer whose clapback lyrics and chest pops we worshipped. She was back.

We watched and cheered as she released bangers, sold out venues, worked harder than ever. Yet today we see the sinister clues we ignored. In a 2008 MTV documentary, Spears said of her team, “They hear me, but they’re not really listening.” That’s a tragically universal feeling, confirmed by the ensuing years of frustrating news for women—from Access Hollywood to #MeToo to Christine Blasey Ford, all of which transpired while Britney was silenced.

But it also sums up our own complicity in Spears’s tragedy. You want a Bugatti? You better work, b-tch. Rereading her ’Gram captions, her lyrics, even her carefully worded public statements, it’s like you can see now how Britney tried to speak her truth—we just weren’t listening.

Released from the conservatorship, Spears is now taking back her quill on the cusp of 40 years old. She has reportedly said she’d like to hang up her mike and retire. Marry her fiancé. Have another baby. Live a quieter life. One of those nights, she might find herself at a Nederlander theater on Broadway, surrounded by her faithful, free to sit back, enjoy a show celebrating her legacy, and maybe even sing along.

This article appears in the December 2021 issue of Washingtonian.