Queers love their symbolism, and wear their colours to show pride and self-respect, to find each other, and in an act of solidarity and resistance. But ever wondered what to wear, and why to wear it?

But first a caveat about my use of the term “queer”, the Q in LGBTIQA+.

In this article, I use “queer” as both a single and collective identity category; a way to identify oneself or of “being queer” – for example, I’m queer, we’re all queer (I wish). This is important, because the primary aim of such a “being” is to challenge and disrupt normative conceptions of gender and sexuality that suggest there’s only man/woman, or straight/gay, boxes for our bodies, minds and bits to fit into.

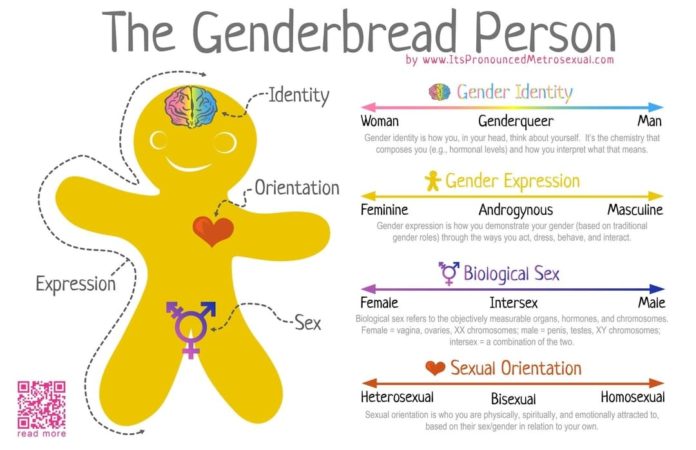

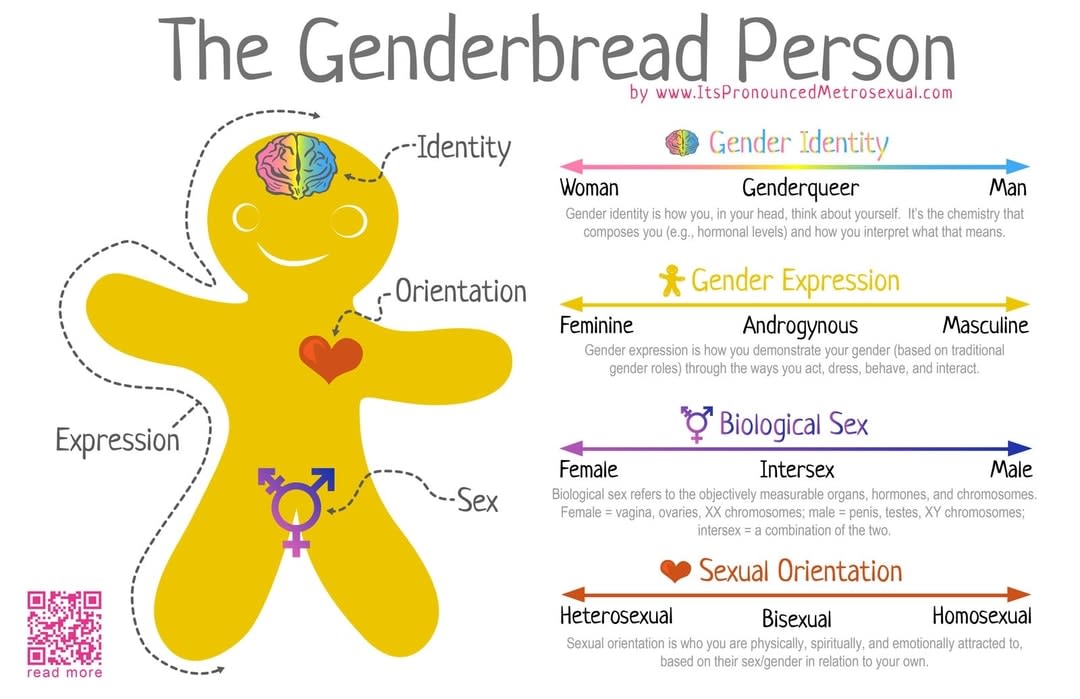

Sam Killerman’s The Genderbread Person provides a solid explanation of these complexities.

I’ll also use it as a verb, an act/action a way of “doing queer”. I’m old-school on this, because I grew up in the ’80s – great music and fashion, bad hair and bad politics, and around the AIDS pandemic, which still lingers with women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa bearing the burden of disease.

This is important, because the primary aim of such a “doing” is political. It’s a form of activism, and a way to rupture, expose and refuse institutionalised systemic inequity, inequality and discrimination based on gender and sexuality and other intersections – for example, of race.

The ACT UP “die in” or “kiss in” is a great example of rupturing, while Sylvia Duckworth’s Wheel of Power/Privilege nicely exposes how some have more than others, and her take on Kimberlé Crenshaw’s notion of intersectionality is spot-on.

Given these explanations and their historic meaning, it’s easy to see why symbolism, even iconography, appeals to “queers”.

Symbols are everywhere

We find symbols in nature, science, art, religion, communities, families, nations, books, online, economies, politics and identities… Yeah, everywhere.

Philosophically, “at its most basic level, a symbol is anything that represents another thing by virtue of customary association due to a conceptual connection or perceived resemblance”.

In a nutshell, symbols are part of every culture and society, and without them we wouldn’t have much to say to each other, or be able to communicate in both obvious and subtle ways.

Language is loaded with symbols, and has symbolism

According to American anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir, symbolism is:

“… the primary way by which humans create meaning, classify knowledge, express emotion, and regulate society. The ineluctably human ability to generate and interpret symbols is, for example, what allows us to differentiate winks from blinks.”

Or in this article, cubs from twinks.

Here the differences are significant, but entirely based upon some agreed-upon social meanings. The basic premise here is that if enough people do, say, agree upon and/or communicate a thing, it can become a symbol and will, when repeated, create systems of knowledge.

Queer symbolism

For “queers”, symbolism provides a way to create social meaning where and when it’s been erased by systems of oppression.

On a grand scale, “queer” symbolism messes with spaces and places, bodies and minds, Jack and Jill, systems and structures, work and school, parks and streets, economics and politics.

On a personal level, these same socio-cultural and political symbols and associated meanings support sex, gender and sexually diverse folk to:

- self-identify as other than cisnormative

- resist categorisation

- make noise, celebrate and disrupt the status quo

- create community and solidarity

- find each other.

Here’s how.

Here, I’m thinking about letters and acronyms – and we sure do have some. Let’s start with IDAHOBIT and then LGBTQIA+.

The former is an acronym used to bring folks together in activism against violence, isms and obias – what we acknowledge on Monday, 17 May. The latter is part of an ever-growing (and rightly so) list of identities under which to self-identify, find community, and rally.

Each is important and personal, and it’s important to appreciate the variation, similarities and differences.

The longest acronym I’ve found is LGBTIQQCAPGNGFNBA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, questioning, curious, asexual, pansexual, gender nonconforming, gender-fluid, non-binary, androgynous), though there’s also a good First Nations addition in LGBTQQIP2SAA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, queer, intersex, pansexual, two-spirit (2S), androgynous, asexual).

Just starting out? You can find a solid glossary here.

Flags: Wear them and wave them with pride

The first Pride flag in all its rainbow glory was a powerful proclamation of visibility. It’s waved and worn, wrapped and adorned at Pride parades around the world. These days there are purported to be up to 30 different Pride flags of various styles, design and colours.

The flags, like the acronyms and the identities they signify, are constantly evolving. Check here for a (near) complete guide to queer pride flags. Or maybe comic pride flags by Xan are more your style.

This makes the Monash IDAHOBIT flag-raising ceremony at Parkville campus on 17 May pretty important.

Ever wondered how “queers” signalled interest among themselves before HER, Grindr or Tinder? Flagging is how.

How to call out violence every day

As shown above, language is important because, when it comes to IDAHOBIT, we’re acknowledging the multiple and ongoing instances of violence against those who “be” or “do” themselves in non-normative ways; we’re calling out the isms and obias. This violence ranges from an askew glance to toilet policing, from institutional incapability to record preferred names to dead-naming, from rejection to homelessness, from a shove to murder.

Violence against “queers” is pervasive. It’s also personal, and that’s where things like IDAHOBIT are so important. It also explains why “queers” love their symbols, and what they symbolise.

Below are some suggestions for continuing the activism into the week and beyond IDAHOBIT.

- Don’t make assumptions. Everyone is not the same! The acronyms, flags, colours and naming makes it very clear that “queers” are both everywhere and different.

- Refuse and call out violence in all its forms. No matter how small the act, it harms people and communities. There is no place for violence against anyone.

- Adopt a “queer” lens on everything. The world is much more colourful when you take away the darkness of bigotry, harassment, the isms and obias. If you see it, refuse it, question it, speak up, stand up, ACT UP.

- Think outside the box. Get in the know about sexual and gender diversity; it’s heart-pumping and mind-blowing. I recommend the links already shared, plus this – The Sexualitree.

- Become an ally. At Monash, we have some great training for staff and students, and our Ally Network.

But mostly, just show your colours. Turn up for yourself and for others, be visible, and stand in solidarity against homophobia, biphobia, intersexphobia, and transphobia.

Pride starts here at the Minus18 online store.

Monash Respectful Communities launches a week of activities, starting on 17 May, centred on the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, Intersexphobia, and Transphobia (IDAHOBIT).