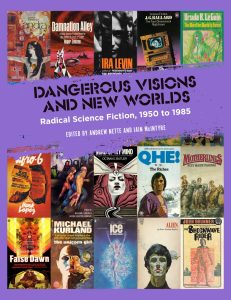

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction 1950 to 1985, Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre, eds. (PM Press 978-1-62963-883-6, $59.95, 224pp, hc) October 2021.

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction 1950 to 1985, Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre, eds. (PM Press 978-1-62963-883-6, $59.95, 224pp, hc) October 2021.

I’m a child of the cyberpunk generation. One of the first genre novels that left an impression on me was William Gibson’s Neuromancer (even if I didn’t entirely understand it). It wasn’t until my late twenties, when I started attending the monthly meetings of the Nova Mob (a Melbourne science fiction club that continues to this day), that I began to appreciate the rich history of science fiction and became aware of the movement that preceded cyberpunk, known as the New Wave. Two decades later, and while I’ve read my fair share of Thomas Disch and Harlan Ellison and dipped into the works of Moorcock, Aldiss, and Ballard, I’m no expert on the period. That’s why I was so excited to read the essay collection Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1985. Edited by Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre, the book features more than twenty essays from a diverse range of writers (including a number of shorter, interstitial pieces penned by the editors) with the aim of charting the radical underpinnings and lasting impact of the New Wave, while shining a light on the luminaries and lesser known authors of the period.

What immediately strikes you about Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is that it is simply gorgeous. While I can’t speak specifically to the production quality (I received a PDF), on my iPad the full-color reproductions and scans of hundreds of book covers from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s looked magnificent. I can only imagine how eye-popping they will be on paper. Even if the essays were poor (they’re not) it would almost be worth buying the book just to stare lovingly at the Penguin reissue of Moorcock’s A Cure for Cancer or the Corgi version of Bob Shaw’s Ground Zeroman or the psychedelic front pieces for New Worlds magazine.

Fortunately, the words are worth sticking around for. Nette & MacIntyre’s introduction does an excellent job contextualising the New Wave within the broader political and cultural revolution of the ‘‘long sixties.’’ This is then followed by Rjurik Davidson’s illuminating piece, ‘‘Imagining New Worlds: Sci-Fi and the Vietnam War’’, initially published a decade ago in Overland. Davidson frames his essay around an event that I was only vaguely aware of: the publication of an advertisement in the June 1968 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction that featured duelling lists of SF writers supporting and opposing the Vietnam War. The piece is a reminder that there’s always been a deep cultural and political divide within the genre. The reprinting of Rob Latham’s lengthy but informative 2006 essay ‘‘Sextrapolation in New Wave Science Fiction’’ explores the ‘‘grown-up’’ agenda of the New Wave, ‘‘to shed the legacy of [the genre’s] pulp past and embrace contemporary realities.’’ The article not only highlights the role of Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds and later Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions in shaping the ethos of the New Wave, but also how the graphic, sexually explicit material published during the period upset the establishment. As an example, Latham cites the infamous incident where a Tory representative in the House of Commons called out New Worlds as ‘‘filth’’ after the publication of the first instalment of Norman Spinrad’s Bug Jack Barron.

For the most part, the remainder of the essays are profiles of the authors – not all of them directly associated with the New Wave – who wrote radical, experimental genre works during the ’60s and ’70s. There are terrific, enlightening pieces on Judith Merril (by Kat Clay) R.A. Lafferty (by Nick Mamatas), Octavia E. Butler (by Michael A. Gonzales), and Mick Farren (by Mike Stax). I particularly enjoyed Erica L. Satifka’s profile of Philip K. Dick, which chronicles the author’s descent into paranoia and the way it was reflected in his later fiction. Similarly, Lucy Sussex and Scott Adlerberg do a fantastic job – in a short space – teasing out the themes explored by Alice Sheldon (Sussex) and the Strugatsky Brothers (Adlerberg) while also detailing the significant challenges those author’s faced. I was especially intrigued by the chapters that explored and critiqued the novels of writers I’d previously been unaware of, such as Hank Lopez’s Afro-6 (by Brian Greene), William Bloom’s Qhe! Series (by Iain McIntyre), and Joseph Denis Jackson’s The Black Commandos (also by Iain McIntyre). And while I found Nicholas Tredell’s critique of six key New Wave texts rather brilliant (I must read Ice by Anna Kavan), and admired Donna Glee Williams’ incisive comparative analysis of Robert A. Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress and Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, my favourite essay (because there always has to be a favourite) was Rebecca Baumann’s brilliant article, ‘‘Speculative Fuckbooks: The Brief Life of Essex House, 1968–1969’’. It’s an engaging, eye-opening deep dive into the erotic gay science fiction published by Essex House.

With its gorgeous interiors and thoughtful, detailed essays, I know that Dangerous Visions and New Worlds will inform newbies like myself while providing those familiar with the subject matter a contemporary perspective on the New Wave’s radical antecedents and the influential foundational texts the movement produced.

This review and more like it in the October 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.