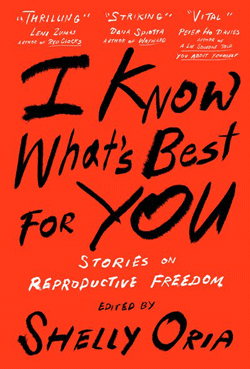

I Know What’s Best for You: Stories on Reproductive Freedom, edited by Shelly Oria, is a multigenre anthology with a focus on the crisis of reproductive rights in the United States. The book’s international supplement features sixteen additional works of fiction, nonfiction, and art by contributors from around the globe. Order the book, and receive the supplement, I Know What’s Best for You All Over the World, free as an e-book. Editor and author Shelly Oria will be touring through the summer of 2022, joined by contributors to the book as well as many other writers and artists.

From now until July 1, 25% of sales of I Know What’s Best for You: Stories on Reproductive Freedom supports the Brigid Alliance. Shipping on this title will also be free through the end of the month. You can give directly to their abortion travel services program here.

– – –

An IUD Called Auny Fatima

by Rasha Khayat

Essay

Germany and Saudi Arabia

I have an IUD. Not an actual one in my uterus, but a tiny one in my brain. It has the shape and voice of my aunt Fatima and it operates not with hormones but with fierce judgment, shame, and emotional blackmail.

I am forty-two, unmarried, and child-free, and honestly, probably not by conscious choice. Some call it bad luck, bad timing, bad this, bad that. I call it: the result of cultural confusion.

Growing up in a culturally mixed household offers many blessings but also many challenges. An exotic mix such as my own—half German, half Saudi—sometimes feels like having to bridge two completely opposite worlds.

When it comes to family politics, growing up with a large Saudi family means: get married young, preferably as a virgin, then have kids. (Don’t have kids out of wedlock. If you have sex out of wedlock, don’t talk about it.) Any other preference or idea for a personal life? Same-sex attraction maybe? Single parenthood? Keep it to yourself or, better, build a fake life that complies with society’s rules. (Gay men, for example, frequently get married to women and then have kids, often by IVF, so all’s well on the surface—a very happy family.)

When it comes to family politics, growing up in Germany means: whatever you want to do, you’re free to do. Gay, straight, single, married, live-in partners—at this point in time, having a family in Germany is allowed for anyone who wants one.

So—what do you do with such a level of freedom on one hand and a very strict, conservative upbringing on the other? You live life as a balancing act. You try to live with the freedom you are given, and at the same time, you try to not offend your family and their values.

As a teenager, I remember vividly how I used to hide my birth control pills and pictures of my boyfriends whenever Saudi aunts and uncles would come to visit us in Germany. On every visit to Jeddah, I remember nodding sheepishly whenever my aunties would say: “Inshallah nshoofik aroosa” at any given family function—“God willing, we’ll see you as a bride soon!” My aunty Fatima tried her best, bless her heart, to be a good matchmaker and introduced me to every prospective mother-in-law in town. I attended the weddings of my younger cousins and celebrated the arrivals of their babies while getting older and still being unmarried. At this point, when we visit Jeddah, Aunty Fatima no longer introduces me to potential in-laws. Nobody professes their wish for me to be a bride soon. I exceeded my shelf life as a good Saudi daughter, wife, mother.

My German friends, on the other hand, took pride in opposing the family model we all grew up with—mother, father, house with a white fence. They sought independence, a career, casual sex. I went along happily; I enjoyed working and having casual relationships. Still, every Eid, every holiday when I received new family photos with more new spouses and more new babies, I felt ashamed I didn’t have anything to show except a successful career, and sometimes, I do see a version of myself in these pictures and for a split-second think: Wouldn’t it be nice? Wouldn’t it feel good to be a part of this? A real part? But I also felt ashamed admitting to my German friends that I might actually want what my family had instilled in me. Why wasn’t I able to embrace the freedom of the country I grew up in?

When you grow up with strong family traditions the way Saudis do, any alternative model, any form of exercising reproductive freedom, is often considered haram—sinful. I always knew I had to avoid getting pregnant as a young woman, so I could avoid getting an abortion. Not because I don’t believe in my own right to choose—I firmly do. But because of the moral judgment, the shame, and emotional blackmail by all the uncles and aunties my parents and I would have faced in such an event, which would mean great shame for my family. I remember clearly how my aunties would whisper on all kinds of occasions about girls who “ran away,” “were sent to Switzerland,” had to “be taken to Europe”—as if these were codes everybody understood—and how these girls’ mothers would not be invited to social gatherings for a while.

For anyone who hasn’t experienced the balancing act of marrying, as it were, two such different cultures, it may seem clear that individual freedom and happiness has to come before pleasing, for example, a conservative family. But it is not that simple. The amount of love, protection, and support you receive from this very strong family apparatus makes it emotionally difficult to allow yourself to do something you know might offend them. And growing up under the influence of two such incredibly opposite cultures can make it equally difficult to figure out what you yourself actually want and how you want to live.

I have seen and experienced many versions of this balancing act. Sadly, when it comes to family models, I haven’t seen a whole lot of success. A female friend of mine, who also has Saudi parents and was raised in Germany, broke off any contact with her family when she became pregnant out of wedlock with a German partner. Many bicultural couples I know find themselves divorced, as the cultural differences seem too difficult to navigate.

I am hardly the only person with a complicated biography who carries an IUD in her head. Who tries to figure things out while also trying to avoid hurting people she loves. In the end, maybe my supposedly subconscious choice to remain child-free wasn’t so subconscious after all. Maybe, following the route my aunty Fatima and the family had set for me never suited my personality in the first place. And maybe my aunty Fatima–IUD actually protected me from a life that was never supposed to be mine.

– – –

Rasha Khayat grew up in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and has been living in Germany from the age of eleven. She writes novels and essays, hosts the feminist podcast Fempire—Women Who Write, translates, and is artistic director of Newropa, a literary activism camp in Hamburg. Find her on her website, westoestlichediva.com, on Instagram @fempire_podcast, and at her podcast’s website.

– – –

See in our store

Order I Know What’s Best for You: Stories on Reproductive Freedom and receive the book’s international supplement, I Know What’s Best for You All Over the World, free as an e-book.