After the disappointments and failures of the response to the coronavirus pandemic, the decline of monkeypox revealed the power of public health to quash disease threats when politics and science align, a community mobilizes to protect its own and medical advancements are deployed expeditiously.

“It is good news to see cases down, but it’s not an invitation for triumphalism or complacency,” said Gregg Gonsalves, a professor of public health at Yale University and a longtime AIDS activist.

This year’s global monkeypox outbreak spread among gay men largely through sexual activity, a pattern scientists said was unusual because the virus typically spreads among a more diverse community through other forms of close contact.

But an aggressive public health response — drawing from decades of lessons learned fighting HIV/AIDS and employing efforts among gay men to raise awareness and encourage vaccination — prevented monkeypox from circulating more broadly.

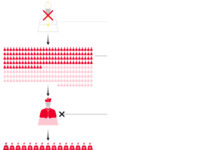

New daily infections in the United States peaked at about 450 in early August, when the Biden administration declared a public health emergency, and have declined to fewer than 10 per day.

Experts caution against prematurely declaring the response to monkeypox — which global health authorities recently renamed mpox — a success story. They fault government agencies for failing to move swiftly enough against a virus for which tests, vaccines and treatment were already available. And it’s unclear how much of the decline in cases reflects government action, rather than the virus’s running out of susceptible people to infect.

Nearly 30,000 Americans contracted monkeypox, which causes flu-like symptoms and rashes. Patients were required to isolate for weeks until the lesions scabbed over, forcing many to cancel plans or lose income. At least 20 people died.

“We didn’t need to have such a large outbreak that persisted all summer and threw many people’s lives into disarray,” Gonsalves said.

One lesson from the monkeypox response is clear, especially after fierce disagreement about coronavirus sharply divided Americans: A common sense of purpose can be a powerful weapon against a microscopic enemy.

“It’s inspiring to see when community, political will and science come together,” said Demetre Daskalakis, the deputy coordinator of the White House monkeypox response, who has spent decades on the front lines of gay sexual health. “This is what we all signed up to do.”

When politics and science align

Episodic reports of gay men developing unusual rashes and unfamiliar illnesses this spring brought back memories of the first AIDS cases in the 1980s. Top figures across public health, research and medical institutions who came of age during that epidemic were determined not to repeat the mistakes of that crisis, when the widespread suffering of gay men was ignored.

“It was malign neglect in the Reagan administration starting with leadership not even wanting to use the word AIDS and the implicit idea that the population was expendable and behavior was not socially sanctioned, so why should we do anything?” said Kenneth Mayer, a co-chair of the Fenway Institute, an LGBTQ health-care provider in Boston.

As Massachusetts reported the first known monkeypox case in the United States, and European officials reported that men who have sex with men were contracting the virus, Mayer braced for an influx of patients. Eventually, Fenway would treat more than 100 monkeypox patients and vaccinate more than 6,600 individuals.

He contrasted the Biden administration’s response to monkeypox with the sluggish actions early in the AIDS crisis, with Biden directly addressing monkeypox and forming a response team, and his administration holding regular Zoom meetings with LGBTQ organizations.

While Mayer and other providers who primarily work with gay men praised the administration for that engagement, they faulted officials for not responding faster. In the crucial early months of the outbreak, testing was difficult to obtain, a daunting amount of paperwork faced those seeking medication, and the vaccine was in short supply.

Anthony Fortenberry, the chief nursing officer at Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, an LGBTQ health provider in New York that treated as many as 30 monkeypox patients per day during the summer peak, said the wave of infections began to crest as the federal government took steps to improve access to testing, treatment and vaccination.

“The quicker we can address barriers to care, the quicker we can get on the other side of these outbreaks,” Fortenberry said.

While monkeypox is curable and rarely deadly, the lesions it causes can be extremely painful, and the virus can force weeks of isolation. It led to especially severe outcomes in people with untreated HIV.

The toll of monkeypox spurred activism in the gay community and placed enormous political pressure on big-city Democratic officials who count on LGBT voters as a key flank of their electorate. Local political officials pressured the Biden administration to expand vaccine availability and to ease access to care.

“Monkeypox happened in the gay mecca cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York, three of the most liberal cities where the government and the academic institutes and scientists and public health were already aligned anyway,” said Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of California at San Francisco who treated monkeypox patients. “If the outbreak was in North Dakota or South Dakota or Texas or Florida primarily, one could have imagined it would have been harder.”

Rochelle Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said the monkeypox response demonstrated how the “biggest successes” in public health often come from those in government and community working side-by-side. She said she regularly consulted gay people to understand how access to testing and medication worked on the ground and how to improve it.

It was a starkly different response from what unfolded four decades earlier amid a different viral outbreak.

“I was in meetings where it was said, ‘Could you imagine what we could have done with HIV if we had meetings with the community as early?’ ” Walensky said.

A community takes charge

Yet, many who worked to quash the outbreak within the gay community paint a far less rosy picture. While they are relieved they did not endure outright hostility from the federal government and had many allies in the response, they noted that gay men still were left largely to fend for themselves throughout the summer.

Doctors were unfamiliar with monkeypox symptoms, which can be confused with other skin conditions or sexually transmitted illnesses, and were unsure how to help patients. Messaging often was muddled as authorities tried to balance acknowledging that the virus was spreading almost exclusively among gay men against fears of stigmatizing that group. And the rollout of vaccines was uneven.

In ways big and small, gay men stepped up for one another.

In D.C., members of a gay kickball league discovered a vaccine site through links shared on group chats. In Denver, napkins at gay bars had QR codes to sign up for vaccine shots. Bathhouses where sexual encounters are common were temporarily repurposed as vaccination sites.

Joseph Cherabie, an infectious-disease physician at Washington University in St. Louis who identifies as queer, said he made himself available to answer questions on Instagram, where many gay men turned for information. He felt it was important for people to hear from others like them that they should consider reducing their sexual activity to minimize exposure to monkeypox.

“If I say that, members of my community hear that much differently than if a White cisgender heterosexual male or a White cisgender heterosexual female said that because you don’t know my life,” Cherabie said.

Joe Osmundson, a microbiologist in New York, was among the queer scientist activists who organized to spread the word about monkeypox, co-writing an article on ways to reduce exposure while maintaining an active sex life, and promoting vaccines at bathhouses and other venues. He coined the term “anal autumn” as something to look forward to after making temporary behavioral changes.

“There was a huge number of us who want to give people information and the ability to make behavioral choices to avoid painful infection without shaming people who like to have sex,” Osmundson said. “It’s sort of a muscle memory in the queer community: We know shame-based outreach doesn’t work, and if you meet people where they are at and provide resources, that tends to be much better.”

Polling suggests he was right.

Nearly three-quarters of gay and bisexual men surveyed in September said monkeypox was a threat to their lives, and two-thirds planned to get vaccinated, according to the Pew Research Center. In August, half of men who have sex with men said they were reducing their sexual encounters and number of partners because of monkeypox, according to a survey cited by the CDC that did not have a random sample.

Jennifer Nuzzo, a professor of epidemiology at Brown University, takes a dim view of the public health response, arguing that it should have been a containment “slam dunk,” given that the world possessed the necessary tools.

“This is not an administration success story by any means. A lot of the success resides within the LGBTQ community itself,” Nuzzo said. “Had it infected another group of patients, I’m not sure we would have done as well.”

Not declaring victory

Although the number of monkeypox cases has plummeted, experts caution that the virus could rebound.

They said they believe people most at risk probably have resumed their usual sexual behavior. If monkeypox establishes itself in animal hosts in the United States, it could become a permanent threat, as it is in parts of Africa. And the vaccination campaign has slowed.

Officials estimate that about 1.6 million Americans are at risk of contracting monkeypox, but only about 430,000 people have received the two-dose vaccine regimen. Nearly 300,000 have received one dose.

Racial disparities in vaccination persist, even though people of color make up most of the newly infected. White people have received almost half of all administered doses, Latinos about a fifth, and Black people about 11 percent. Remaining doses have gone to Asians, people who are multiracial, or recipients for whom information on race or ethnicity was not available.

“I think we will get to zero” cases, said Robert J. Fenton Jr., coordinator of the White House monkeypox response. “The question is how long can you sustain that, and that’s really going to depend on vaccine uptake.”

Walensky said public health authorities need to be especially vigilant as Pride festivities and large gay gatherings resume next summer and a new generation of teenagers and men not previously infected or vaccinated becomes sexually active.

CDC research showed that at-risk unvaccinated young men were 10 times more likely to become infected than someone who received two shots.

And while the United States was able to dramatically expand access to the monkeypox vaccine, shots remain hard to come by in Africa.

“Just because we are not seeing cases doesn’t mean we can certainly declare victory,” said Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at Los Angeles who has studied monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of Congo for two decades.

“One of the big root causes of this is because we have failed to deal with monkeypox at the source in places where we know it’s likely still spreading,” she said.