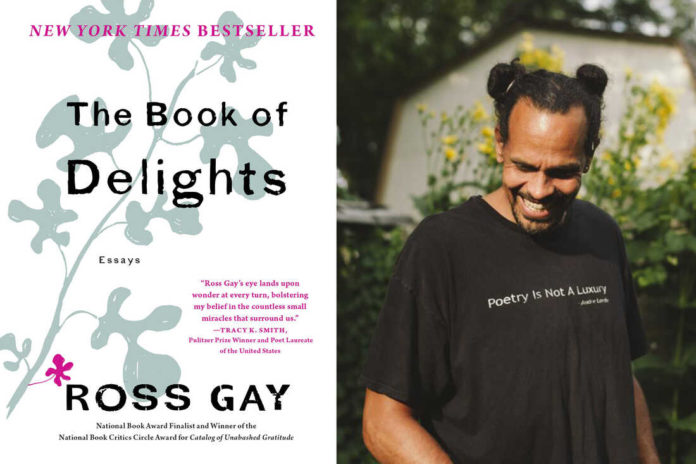

Natasha Komoda/Courtesy of Algonquin Books

This summer on Code Switch, we’re talking to some of our favorite authors about books that taught us about the different dimensions of freedom. In the last installment, we caught up with the romance writer Helen Hoang to talk about sex, love and autism. Today, we’re sitting down with the writer Ross Gay.

So many things delight Ross Gay: handmade infinity scarves and loitering, the joy of carrying a heavy bag between two people, paw paws and even weeds. The author and poet began writing daily essays on things that delighted him when he turned 42; those reflections became the basis of his 2019 collection The Book of Delights.

The book is filled with such joy and effusiveness that I find myself revisiting it over and over again. Over the years, it has offered me a template for how to hold the good with the bad, to be more present, and to revel in the little things. This summer, I reread it yet again and found myself meditating on a desire Gay had voiced: wanting to be softer in a world so ready to sharpen us and to make us hard.

So, in a recent interview, I talked to Gay about that desire, as well as the role of joy in daily life, the difficulty of allowing yourself to be moved, and why he thinks it’s important to use the word “love.” Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you describe a moment when you felt free?

So I’m writing about joy. The thing is, I’m not exactly sure what joy is. I’m constantly trying to wonder about it. In fact, I’d tell you, that’s one little definition of freedom I enjoy: wondering about joy with other people. I am writing because I’m thinking about these moments where I have felt the immense experience of joy.

For instance, I’ve worked for years on this project called the Bloomington Community Orchard. Within about eight months, we planted this orchard. And since then, it’s been cared for by so many people. When we planted that orchard, there was the feeling of watching those trees go into the ground and thinking about all of that labor, all of that care and all of that struggle, too. But I think everyone felt that it would be something that we together could make that might care for people we do not know, and might care for people in the future who we could not imagine.

And I can just remember it plain as day, when I was leaving that day, my eyes were welled up. I was just so filled up, and I was so profoundly indebted to these people — and it’s a lot of people. There were all the potlucks, all the arguments, all the going to get limestone, all the talking about what kind of trees there were going to be. I’ve been thinking about that as joy, but I’m also going to say I think maybe that was an experience of freedom.

When I read your book this time, I really sat with what you were saying about wanting to be softer. And I think it offers this roadmap of someone saying, it’s OK to love things, and it’s OK to feel joy. There is a lot of freedom in that: in finding something delightful, taking time with it and sharing that joy.

Yeah. One of the projects of the book is allowing oneself to be moved. And I think one of the studies in the book is that to be moved is to be connected. To be moved is to be alive.

I think for any number of reasons, I have wanted to participate in the brutal fantasy of not being movable. I’ve wanted to imagine myself as a discrete creature that is not movable. You know, I grew up playing college football, and a lot of my training was about how to be unmovable.

But to be moved, it’s all kinds of things. It’s tears, and it’s shock and it’s flabbergasting. And it feels like a profound sorrow when I am reluctant to say, I love this, I love this. I’ve never seen anything as beautiful in my life; that flower gives me a reason to be alive.

I teach, and last year I started class off like this: “Tell me something that was beautiful that you saw on the way to class.” And it can be really challenging for people to say it, because it feels vulnerable. Once you’ve admitted that, you’ve also admitted that you’re movable, which I think also is an admission that you have needs. I’ll say, “Say something that you love, that you realize you loved in the last week or so.” And not only is it difficult for people, it’s amazing how quickly people turn the word “love” into “like”: Oh, I like that. And I have to be like, Let’s go with love. What did you learn that you love in the last week? Which is to say, What did you learn that you were really moved by in the last week?

Yeah, I was doing a writing exercise last night, and it was to write, “I love it when…” And I found myself turning it sarcastic!

I’m telling you! To be like, “I love it when you just touched me on the arm and said, ‘Are you OK?'” Or, “I love it when you drop off seeds for the garden.” The experience or the understanding of one’s need, also puts us into this other thing, which is realizing, Oh, I’m grateful. You know, I think a lot of imaginations of freedom do not hold gratitude. But the fact is that we are constantly in profound need, which makes gratitude a deep and fundamental aspect of our lives.