“You’ve got Palestine, you’ve got Israel, yet somehow the biggest asshole is Ramy,” says Ramy creator and star Ramy Youssef. Photo: Adel Kamal

Ramy Hassan does many potentially unforgivable things over the first two seasons of the Hulu series named for its creator and star. Namely, he cheats on his fiancée with his cousin the night before his wedding, ending not only his marriage but his relationship with his spiritual leader and, briefly, father-in-law. Somehow, though, this isn’t Ramy’s lowest point. That’s achieved in the ambitious, uncomfortable, and exemplary season-three episode “Egyptian Cigarettes.”

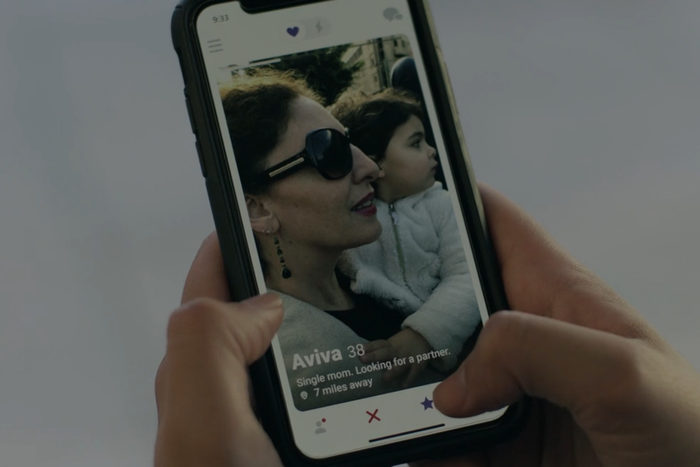

When season three begins, two years have passed since Ramy’s wedding and subsequent confession of infidelity. Divorced and ashamed, he’s thrown himself into work with diamond-dealing Uncle Naseem (Laith Nakli), and by the season’s second episode, “Egyptian Cigarettes,” Ramy agrees to take a trip to Israel to meet with a group of Orthodox Jewish jewelry suppliers. But after they arrive, things unravel quickly: Uncle Naseem is detained at the airport, and Ramy’s meeting with the head of the Diamond Club includes assumptions and insults on both sides. Catastrophe officially strikes after Ramy tries to squeeze in a Tinder date before his big dinner with the suppliers. He loses track of time, and in a desperate attempt to avoid being late, makes a series of decisions that result in the detainment of a Palestinian teen by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), a traumatizing moment for the child and his family with hundreds of real-life comparisons.

“Egyptian Cigarettes” is the culmination of Youssef’s long-held desire to set an episode in the Palestinian territories and a rare instance of an American-set TV show depicting the daily lives of Palestinians who live in the occupied areas of the West Bank. For Ramy, a portrait of a Muslim American family living within the Egyptian and Palestinian diaspora, “Egyptian Cigarettes” allowed the series to step outside itself to interrogate its characters’ western perspectives. Production traveled to Israel to film scenes set in the West Bank city of East Jerusalem, and the episode features two young Palestinian actors.

Planning such a shoot was already complicated thanks to Israel’s stringent permit system regulating how and when Palestinians can leave the territories. Then, just before cameras rolled in May 2022, tragedy struck: The Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, a friend of members of the local crew, was shot and killed in the Jenin refugee camp. Out of respect for those mourning Abu Akleh’s death, Ramy’s production team chose not to film in the West Bank and shot entirely in Israel instead. Nonetheless, the show took pains to depict reality inside the Palestinian territories, centering the Israeli-built separation wall the United Nations has deemed illegal and the hundreds of roadblocks and checkpoints the IDF uses to restrict Palestinian movement. The result is a quietly radical pushback against western stereotypes of Palestinian people that makes space for the Palestinian experience’s “brutality and honesty and sweetness,” according to episode director Annemarie Jacir.

Ramy (Ramy Youssef) and Rasha (Yara Jarrar) inside her apartment in East Jerusalem. In real life, the scenes were filmed in Haifa, Israel. Photo: Hulu

The Ramy writers began working on the episode in February 2021. The idea was simple: “You’ve got Palestine, you’ve got Israel, yet somehow the biggest asshole is Ramy,” Youssef explains. “Putting him in the middle of this felt like a natural evolution for our show.” He just needed a reason to be there. So in the season-three premiere, Ramy’s new friend and fellow Diamond District employee, Yuval (Julian Sergi), connects him with the Diamond Club — described by Uncle Naseem’s Jewish colleague Daniel as “criminals.” Despite his previous support of the BDS movement, which promotes boycotts, divestments, and economic sanctions against Israel, Ramy eventually agrees to travel to Israel to meet the group’s boss and Yuval’s aunt, Ayala (Smadi Wolfman).

With their setup in place, the ten-member writers’ room turned to tackling facets of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that Youssef says aren’t “in the American discourse.” The script needed to do several things at once: center Ramy’s American political education and its gaps, show the military occupation’s effects on Palestinians living under it, acknowledge the horrors of the Holocaust and the subsequent creation of Israel as a Jewish homeland, and poke at what co–executive producer and episode co-writer Maytha Alhassen calls the “faith washing” that misconstrues Israeli-Palestinian tension into a Jewish-Muslim issue. At the same time, Alhassen says, it was essential to honor the opinions of Palestinian refugees she’d met years earlier who told her, “We don’t want one state or two states. We want no states.”

Involving people in the writing process “who are and grew up differently politically positioned on this issue” was crucial, Alhassen adds.

The writers’ room landed on four main characters:

➼ Ayala (Smadi Wolfman), a Zionist, who is wary of working with a Muslim partner and approaches Israeli military policy toward Palestinians with resigned acceptance. At one point during her meeting with Ramy, she asks him to draw the Islamic prophet Muhammad to prove he’s not a zealot. Only after he reaches for a pen does she claim she’s kidding.

➼ Rasha (Yara Jarrar), a Palestinian woman and lingerie-company founder living in East Jerusalem who matches with Ramy on a dating app. She explains to him that the conflict in Israel isn’t about Judaism and Islam, but about the Israeli government’s insistence that it’s fighting a war when the Palestinians have no army.

➼ Khaled (Wadia Jazmawi), a Palestinian teen who encounters Ramy at a checkpoint.

➼ IDF interrogator Noam (Ilan Muallem), an agent of the Israeli state who questions Uncle Naseem after he is detained at the private hangar. At first he questions Naseem’s Palestinian identity, but after seizing Naseem’s phone and finding the gay-hookup apps, Noam takes on a more flirtatious tone.

The writers decided to build the climax of the episode around Ramy and Khaled. When the Palestinian teen runs into Ramy at a checkpoint and mocks his attempt to use an American passport as some sort of express ticket, Ramy has no qualms about stealing Khaled’s bike to return through the checkpoint for his meeting with Ayala later in the day. In turn, Khaled and his friends chase down Ramy and steal his jacket and passport. When Ramy reports the theft to the IDF, the soldiers then raid Khaled’s home and drag him into their custody while a stunned Ramy stands by. Ayala, by promising to use her government contacts to help free the teen, convinces Ramy to go into business with her. With the Khaled situation seemingly taken care of, Ramy focuses on establishing a rival jewelry business opposite Uncle Naseem, his self-absorption fueling the season’s exacerbating sense of doom.

From left: Ramy executive producer, writer, and season-three actor Adel Kamal; “Egyptian Cigarettes” consulting producer and actress Hiam Abbass; episode director Annemarie Jacir; actress Smadi Wolfman; actor Julian Sergi; actor Peter Macdissi. Photo: Ramy Youssef

Preparing to film abroad was rigorous. Although co-writers Youssef and Alhassen had each visited the Palestinian territories in 2015, they knew they needed local input. Youssef asked decorated Palestinian filmmaker Jacir to come onboard as a guest director, and Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass, who was born and raised in Nazareth and plays Ramy’s mother Maysa, agreed to serve as consulting producer.

With the script requiring most of the scenes to be filmed on location, the Ramy team had to secure work and travel permits for crew members who lived in the West Bank to travel into Israel for production. West Bank actors Wadia Jazmawi and Abed Al Nasser Al Sadi, who were cast as Khaled and his friend Yusuf, also needed authorization from the Israeli government to leave their home city of Jenin. Clearances for the crew arrived, as well as unprecedented shooting access to the Qalandia checkpoint. But Jazmawi — who at 15 years old had never been outside Jenin — and Al Nasser Al Sadi were first rejected. Youssef and Jacir refused to cast backup actors. “If anyone is going to be able to get them a permit to be part of something like that, it’s an American production, okay?” Jacir says. “If we were on our own, yeah, we definitely would have been rejected. But this is a big deal. It’s Hulu, it’s Disney. It’s as big as it gets.”

Jazmawi photographed on set by Youssef. Photo: Ramy Youssef

It took three letters written by Alhassen and producers’ assistant Nora Mohamed, but the teens were granted approval to leave Jenin. Before filming began, Mohamed and executive producer Tyson Bidner took the boys to Haifa’s Carmel Beach so Jazmawi could see the Mediterranean Sea for the first time.

The episode’s production coincided with a particularly fraught time: During the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, Israeli security forces attacked and arrested hundreds of Palestinian worshippers in East Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa mosque. Palestinians responded with rockets and the Israeli government with bombs, and the escalation of the violence was significant — nearly five times the number of Palestinians were killed by the Israeli army in that period in 2022 compared to the same time in 2021. Then, on a scouting day for the combined American and Jerusalem teams, the news broke that Abu Akleh had been shot and killed.

“We were on a bus, location scouting, and the person sitting next to me had worked with her for years and was immediately in shock,” Youssef says. “The weight of it is almost not grasped in the U.S. This is like if Anderson Cooper got sniped. That really dashed all our hopes of being able to actually cross over.”

Jacir, her crew, and the Americans on the production team attended Abu Akleh’s funeral, where IDF officers attacked members of the procession. The streets were tense after that, Jacir remembers. She intended to use IDF-branded uniforms and Jeeps as props in the scenes shot in the West Bank, and producers worried the costumes and vehicles would confuse actual IDF soldiers and Palestinians in the area. So Youssef and Jacir made the difficult choice to avoid a worst-case scenario: Instead of five days of filming in the West Bank, production would occur primarily in Israel: in West Jerusalem, Haifa, and Baqa al-Gharbiyye. Only B-roll would be captured at the Qalandia checkpoint.

“We can do anything in Palestine, and I’m convinced of it,” Jacir says. “But we also have to protect the crew and the cast, and if things are tense, all it takes is one person somewhere to react, and things can blow up really fast.”

Filming for Uncle Naseem’s scenes began in early April 2022 in New York. COVID-19 restrictions and a time crunch meant Youssef directed the interrogation scene, while Jacir — who flew in for a whirlwind two-day schedule of prep and filming — handled the scenes in the airplane and hangar.

Nakli pulled from his own experiences as a Syrian and English immigrant who’s lived in the United States for decades but was interrogated numerous times in American airports after September 11, 2001 — the “worst time of my life.” His approach resulted in two improvised moments. In the first, Uncle Naseem flips off the security camera and snarls the profanity “sharmuta” after his detainment. The hotheaded Naseem losing his temper isn’t exactly new, but here it’s one of the few occasions when his ire is in response to an objectively awful experience.

The second comes at the subplot’s end, when Noam informs Uncle Naseem he’s being sent back to the United States. After previously teasing Naseem about the gay-hookup apps on his phone, Noam caresses his face — a directive Youssef gave Muallem without telling Nakli. Acting on instinct, Nakli mirrored the gesture and delivered a short and direct “Fuck you,” which inspired such a loud guffaw from Abbass — also present on set that day — that they had to film the take again.

“All of Uncle Naseem’s comedy comes from pain,” says Nakli. “I never try to be funny, I just stay true to the circumstances.”

“No one has ever, between script thoughts and what she did on set, earned a producer credit quite in the way Hiam did,” Youssef says of the actress, pictured with the actors cast as Khaled and Yusuf’s friends. Photo: Ramy Youssef

Filming began in Jerusalem, with Jacir leading the cast and crew in a moment of silence for Abu Akleh. In the episode, Ramy travels from Ayala’s mansion to East Jerusalem after matching with Rasha on Tinder and is surprised to find he must move through a checkpoint to arrive at Rasha’s home. Those scenes were shot in a neighborhood divided by the actual border wall Israel began building in 2002, and that location allowed for a conversation between Ramy and his cab driver about how the more-than-700-kilometer-long barrier doesn’t show up on Google Maps.

After Jacir and Youssef decided to film only B-roll at Qalandia, the production-design team got to work building the checkpoint where Ramy meets Khaled and Yusuf on a soundstage in an industrial district in Haifa. Because the inside of Rasha’s apartment was also shot in Haifa — not the neighborhood in Jerusalem where Ramy encounters the actual border wall — the team also manufactured a facsimile that is seen through Rasha’s windows as she ruefully discusses the seeming permanence of the aforementioned checkpoint. Youssef remains amazed at the surreality of the show’s Palestinian crew “building a wall to talk about the wall that is such a source of entrapment,” but Jacir, who describes her team as “experts in building checkpoints” because of how infrequently Palestinian productions are given official access, is unfazed.

Jacir still speaks with wonder, though, about the production’s packed itinerary. In Baqa al-Gharbiyye, Ramy stealing the bike, the kids giving chase, and the raid on Khaled’s mother’s home were all filmed in one 15-hour shoot, a schedule that Jacir describes as “more than full.”

And location manager Tareq Mbayed managed to secure a gorgeous shot of Ramy noticing the gold Dome of the Rock by staging a seemingly broken-down truck and concerned civilian at the bottom of the hill, Alhassen says. The pause in traffic allowed the cameras to capture the moment uninterrupted.

Throughout the shoot, Abbass was invaluable as a consulting producer. Her ability to speak Arabic, Hebrew, English, and French and her ease with the extras made her an indispensable member of the crew. “No one has ever, between script thoughts and what she did on set, earned a producer credit quite in the way Hiam did,” Youssef says. Alhassen particularly appreciated Abbass’s cultural insight and knowledge of Palestinian history. “In certain moments, she would turn to me and say, ‘Do you see that cactus there? That’s how we know there was a Palestinian village, because you can’t get rid of the cactus.’”

As Abbass put it, “Everything was really incredibly challenging and beautiful at the same time.”

At the end of the shoot, Jacir’s director’s cut was 45 minutes (“Half a feature in five days — that’s insanity to me”). In an amusing bit of resourcefulness, Alhassen and Jacir were depicted as the two other women on whom Ramy swipes right before matching with Rasha:

Ramy co–executive producer and episode co-writer Maytha Alhassen (left) and episode director Annemarie Jacir. Hulu.

Ramy co–executive producer and episode co-writer Maytha Alhassen (left) and episode director Annemarie Jacir. Hulu.

Narratively, “Egyptian Cigarettes” sets up an agonizing character arc for Ramy: He learns later in the season that Khaled is still in IDF custody because Ayala reneged her offer of assistance, a discovery that jars Ramy out of the capitalist ideology driving his estrangement from his family, community, and faith. The episode’s title, “Egyptian Cigarettes,” refers to how the pictures of diseased lungs that many countries — but not Israel or the United States — depict on cigarette packaging display the consequences of potentially destructive choices. “To have a picture of those organs — these effects are really real,” Youssef explains. “When are we going to look at that photo? I view the Ramy character as a symbol of how complicit we are in the large scale of the world, even as we’re navigating our own small piece of it.”

And practically, “Egyptian Cigarettes” depicts the day-to-day obstacles — interrogations, detainments, checkpoints, the separation wall, a constant military presence — that the citizens of the Palestinian territories face every day, a stark reminder of the normalized harm of nation-states.

“You don’t have to really say anything else,” Jacir adds. “In terms of the shooting, the wall, the checkpoints; the fact that in reality, those boys are not allowed to get out of Jenin; everything about our reality. We didn’t have to say to anybody, ‘What is a military occupation? What is life like here?’ It just is.”

Youssef describes it as a “human crisis,” emphasizing, “I’m not going to call it an issue.”

The episode was almost named “Chomsky,” Youssef says, after the American philosopher Noam Chomsky quoted by Rasha: “What Chomsky talks about is the things that you have to do to become a nation and to stay a nation. They’re so cruel.” The reference was suggested by a Jewish member of the writers’ room, adds Alhassen.

According to Alhassen, Youssef wrote the line of dialogue in which a soldier attempts to comfort Ramy: “The NYPD come here every year to train us.”

Youssef with the 1001 Laughs Palestine Comedy Festival, and Alhassen as the co-leader of a trip with the social-justice organization Dream Defenders.

The Qalandia checkpoint stands between Jerusalem and the northern West Bank and is operated by the IDF. Palestinians who live in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, must cross through the checkpoint to reach other areas of Jerusalem and Israel.

During location scouting in Baqa al-Gharbiyye, a group of boys on electric bikes started following the crew around, making them a natural choice for casting the friends who aid Khaled and Yusuf after Ramy makes off with the former’s ride.

Played by the episode’s production designer, Nael Kanj.

The teams were able to pray here during filming.

The cactus is a Palestinian symbol of resilience.