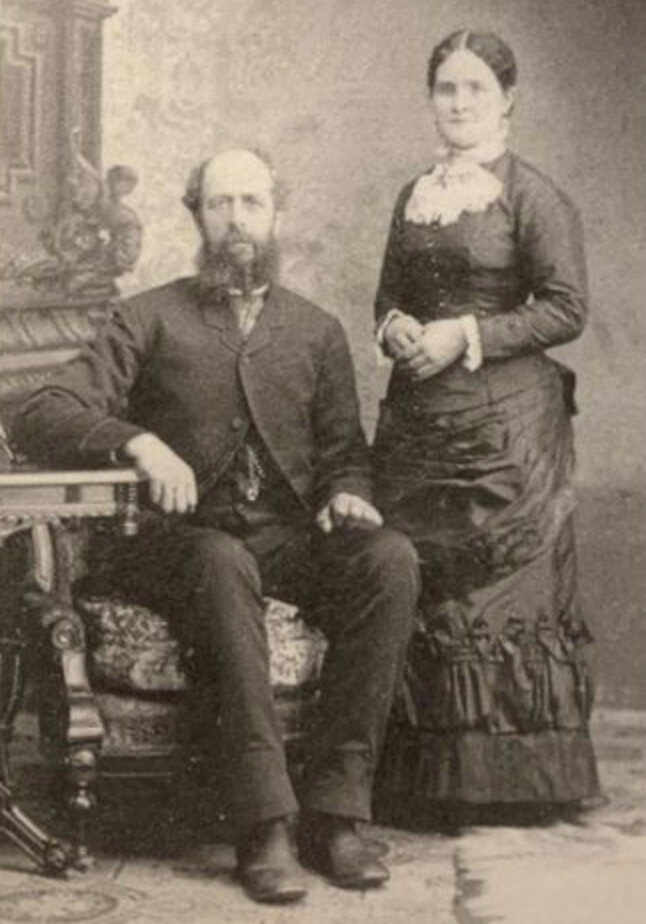

On June 4, 1871, Sara Baines hopped down from a wagon at Fort Bridger, a remote military and trading outpost at the crossroads of several pioneer trails in what would one day become Wyoming. Baines, a 24-year-old seamstress from Louisiana, had just spent several months traveling 1,500 miles through road-less territory, alone. But she wouldn’t be alone for long—she’d come to Fort Bridger to get married.

The groom was Jay Hemsley, a 48-year-old farmer who’d left Ohio some years before to seek his fortune out west. The two had met after Hemsley responded to an ad placed in the matrimonial pages of the October 12, 1869, edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. They corresponded via letter for more than a year before Hemsley proposed. The day after Baines arrived at Fort Bridger, they were married by the fort’s minister in a small ceremony on the banks of Groshon Creek. The next day, they left to open a general store in Placerville, California, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. The Hemsleys were married for 51 years.

It seems like a tremendous risk—traveling thousands of miles into lonely territory to marry a person you met through an advertisement in a newspaper—but it was a gamble that many men and women in the 19th century were willing to take. It’s not quite the same gamble today, but that approach to finding a companionship, a partner in a life that can otherwise be lonely, is still important in 21st-century rural life.

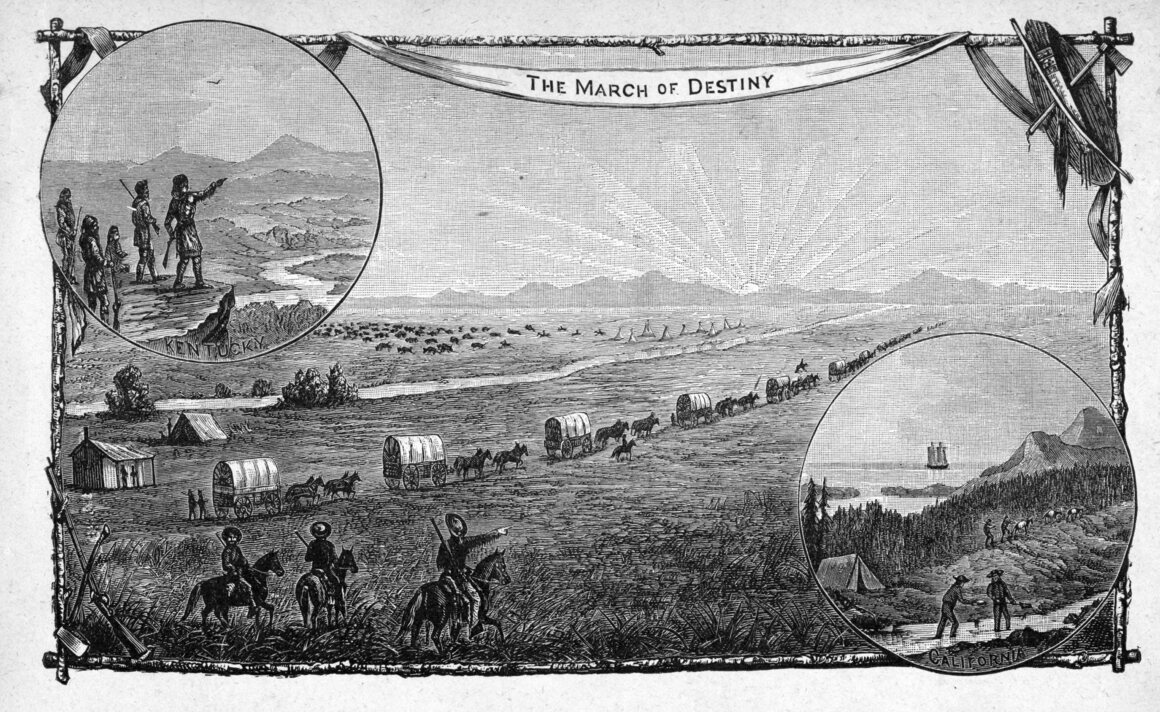

The rise of personal and matrimonial ads—appeals for companionship in newspapers and magazines, as well as in specialist publications devoted entirely to matchmaking—in 19th-century America was a then-modern solution to an age-old problem. “The development of personal ads track the populating of America,” says Francesca Bauman, who wrote about Baines and Hemsley in her 2020 history of the American personal ad, Matrimony, Inc. Put another way, without personals, Manifest Destiny—flawed, damaging, racist doctrine that it was—couldn’t have, well, manifested.

America at the time was expanding at a tremendous rate, unprecedented for virtually any modern nation. The signing of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, for example, nearly doubled the size of the country with the flourish of a pen, and over the next 50 years, millions of square miles were added through wars, purchases, and the killing or forcible removal of the Native Americans who already lived there.

The first white people who moved into these territories were often single men: According to the 1840 census, men in Wisconsin, for example, outnumbered women two to one. The farther west, the more obvious the lack of women—one California newspaper claimed in 1859 that male settlers in the recently minted state outnumbered women 200 to one. (If that figure is exaggerated, it wasn’t by much).

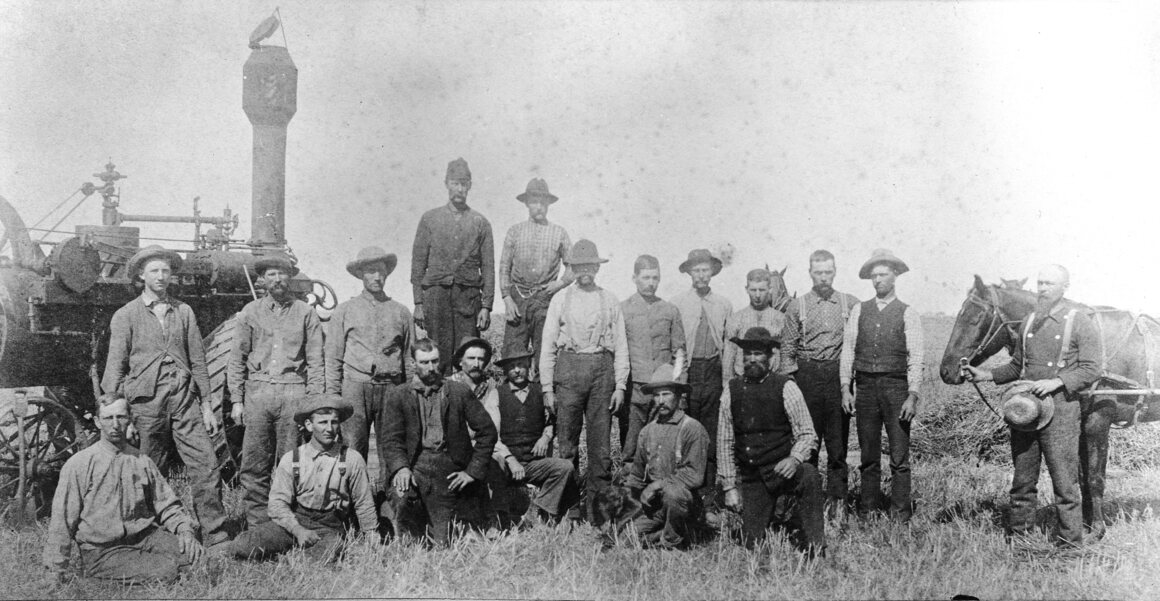

Exploiting those huge tracts of land—which were, again, not unused or unoccupied—meant more than just flinging people out into the vastness and hoping they’d take root. The U.S. government knew that. One homesteading act offered 320 acres of land to a single man, but 640 to married couples. People also needed partners if they expected to be able work that land or keep a house, and they needed community and infrastructure for support and protection. That meant marriages. “We have goods enough,” said a California man, according to a report that appeared in the Indiana State Sentinel in 1849, “now give us some wives.” The question was, of course, how?

“Whenever you’re geographically isolated, you’re always going to be needing a bit of help and support finding a wife or a husband, because you’re not going to meet them down at the store or at church or through a friend. That ain’t going to work,” says Beauman. “Newspapers became an essential way that farmers, anyone who was geographically isolated, was going to find a spouse—both for men and women.”

The invention of the steam printing press in the early 1800s meant that newspapers were becoming easier to produce, and therefore cheaper and more widespread. The first personal ad in America, according to Beauman, was placed in the Boston Evening Post in 1759 (“Any young lady, between the age of 18 and 23, of middling stature, brown hair, of good Morals …”), and by the end of the century, newspapers in every state carried them. Urbanization and population growth driven by mobility and immigration meant that the usual methods of forging relationships and connections—established friends, families, religious leaders, social circles—weren’t always available. But newspapers and access to the wider society they represented were available: “With any new media, the first use is to build relationships,” says Beauman. This was the same story, with the added pressure of the dramatic gender imbalance that was unfolding in other parts of the country.

By the middle of the 19th century, personal ads were semiregular features of most newspapers, and some canny entrepreneurs began selling broadsheets, such as Matrimonial News, that only carried marriage ads. These markets expanded with the country, as the railroads and telegraph wires that increasingly crisscrossed the nation enabled the easier spread of both people and information.

At the same time, it wasn’t just bachelors who needed partners. An observer in a Philadelphia paper in 1837 reported a “superabundance” of women in urban areas back east, a big problem when roles for women in society were largely restricted to marriage and domestic work, such as sewing or laundry. “The economic opportunities for women at the time were very, very limited and pretty miserable,” says Beauman. “So while it might seem like a pretty big leap that your best option was to travel thousands of miles to marry a man you’d never met, for many women, it did seem like the best option.”

Women in the east also actively placed marriage ads seeking matches with men out west. In July 1880, for example, a Mrs. Sarah Wilcox of Fall River, Massachusetts, placed her ad in the Weekly Arizona Miner of Prescott, Arizona. “Wanted! A few gentlemen correspondents with a view to matrimony, by a middle-aged Widow Lady.” There was real risk of death, violence, and isolation attached to the frontier, yet many women still went, which underscores how little there was for them in the “civilized” parts of the country, says Beauman. “It would have been pretty grim, but exciting, better than sitting in a tenement building, sewing.”

Personal ads from The San Francisco Examiner from 1894. Public domain

Personal ads from The San Francisco Examiner from 1894. Public domainSocially, personal and matrimonial ads were regarded by some with a mixture of amusement, skepticism, and fear. “People always worried about the breakdown of society,” says Beauman, particularly the fact that people of all classes were represented on the page, that some ads were too nakedly transactional, and that, by the 1870s, some ads were looking for marriage and others explicitly for “fun.” This ambivalence was evident in how papers wrote about marriage ads. According to one possibly apocryphal but definitely amusing story that circulated in newspapers in 1854, “One chap out west tried advertising for a wife. It worked to a charm as usual.” In response to his ad, he allegedly received 794 letters, 24 shirt buttons, 17 locks of hair, 13 daguerrotypes, two gold rings, one copy of Ik Marvel’s 1850 bestseller Reveries of a Bachelor, and one thimble. “He ought to be convinced,” the Hartford Courant remarked. In 1910, the Wichita Eagle reported with sardonic glee that a Miss Effie Newland, “one of the wealthy young women of Hoxie [Kansas],” married “a Mr. Lopez, a sailor of Key West, Fla.,” after she “jokingly” responded to his ad for a wife. “But Lopez was a splendid writer and the girl soon became infatuated with his lovemaking,” the paper claimed. Lopez traveled to Hoxie and the couple “were married while the parents protested.” Other stories fueled the panic that marriages made outside the bounds of society were dangerous. The Los Angeles Herald reported on October 31, 1897, that a 32-year-old man shot and killed his “heavily insured” 19-year-old wife, whom he’d met through “an advertisement in a matrimonial paper.”

Of course, stories with happy endings—marriages that didn’t end in murder, abandonment, abuse, fraud, or divorce—were also written about in newspapers, and helped popularize the practice. One headline from 1907 declared, “Girl Writes in Secret and Wins a Rich Planter,” the story of an Indiana woman who met her husband through an ad in a matrimonial paper. The pair spent three years writing to each other in secret and married the day they met in person. This may be why personal ads endured. There was evidence that they worked, even for people in remote areas—just as there’s evidence that they or, to be more precise, dating sites and apps, still work.

Most of us are not now hacking out a farm on the dusty plains, the nearest neighbor a day’s wagon-ride away, or panning for gold in mining camps reachable only by donkey. But people do live in geographically or socially isolated areas, just like the men and women who created communities in the frontier.

Jemma Page didn’t travel thousands of miles in a dusty wagon to meet Mark Perry for the first time, but she did drive 100 miles to have a drink with him in a pub in a country hotel.

Page, a high-end furniture dealer living in a small Hampshire, England, village, had recently become single after a 10-year relationship. Perry is a former head gamekeeper at Sandringham Castle and now the head groundskeeper at a country estate hotel in Devon, where he lived. They met through MuddyMatches.co.uk, a British dating site specifically for people who live in geographically isolated areas and want to stay that way.

“Although my village has a very diverse population, they’re all couples or really old or they’re gay,” explains Page. “Great fun, but I really wasn’t going to meet anyone through the village. Whilst I was loving my dogs and walks in the woods and social life, when I became single I thought, ‘Blimey, I’m never going to meet anyone.’” Some friends convinced her to sign up to MuddyMatches and after a few false starts, she met Perry; they were engaged within a year of meeting online. As of March 2021, they’d been living together through the pandemic, taking care of the grounds and animals at Perry’s hotel, which has been closed during intermittent lockdowns. “I really appreciated shoveling chicken shit all day,” says Page.

MuddyMatches certainly isn’t the only site carrying on the tradition of 19th-century personal ads— FarmerWantsAWife.com and FarmersOnly.com in the United States are among the others—and they, too, have seen significant growth over the last few years. Even before the pandemic, more and more people were working remotely. People fed up with the high cost of living in larger cities such as San Francisco and New York began leaving for smaller cities and towns, such as Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Bend, Oregon. Though claims that people were fleeing cities during the pandemic are overblown, there is evidence that densely populated urban centers are growing much more slowly than other areas.

“We have seen huge growth over the last 12 months … it’s all coming out of big towns and cities,” says Andrew Mitchell of MuddyMatches. “I think the slower pace of life that lockdown has brought has given the nation breathing space to think about what’s really important.… The countryside has been beautiful for the last 600 years, that’s not changed, what’s changed is the people’s attitude and appetite for it.”

That’s one of the biggest differences between the people finding partners through MuddyMatches and the people who did using personal ads in the 19th century—a country or rural life can often be a choice today, rather than a necessary escape from social and financial pressures. But there is a thread that runs through the personal ads that helped settlers in the American West: People need people. And they’ll find a way to meet each other, even if that means gambling on a 25-cent ad or a profile on a dating site.

“It’s a leap of faith, right?” says Beauman. “These frontier wives, it’s a more obvious leap of faith, but we know that any marriage is a leap of faith—you never really know what you’re getting into. You never know what the future holds.”